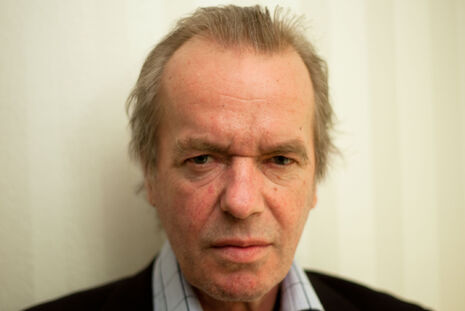

Book review: The Rub of Time by Martin Amis

William Poulos finds much to be admired in Martin Amis’ new essay collection

The New World continues to fascinate the Old; not any more with its gleaming riches, but rather with its sordid curiosities, the stuff any other country would want to keep under the bed or in the back of the closet. America, the slatternly muse, inspires Amis’s best writing. His most successful novel, Money, is largely set in Los Angeles, and the USA is the main setting for Amis’s new collection of essays, The Rub of Time. In it, he includes filial pieces on two American novelists, Saul Bellow and Vladimir Nabokov, continuing the fine tributes he has previously made to the work of both men. What Amis hasn’t given us before is his account of playing poker in Las Vegas, where he distinguishes the various sounds with the ear of a novelist:

“This city is noisy. The whoops from the craps tables (all yea and ooo and aw), the continuous and cutely variegated birdsong of mobile phones (’What’s good, buddy?), and the madhouse nursery jingles of the slot machines, horribly prolonged and as pleasing to the ear as a defective car alarm, and then the cataract of coins into the acoustically enhanced money trays.”

“At the 2011 Republic Party convention in Iowa, Amis describes the presidential election as between the bowel of America (the Republican Party) and the brain of America (the Democratic Party)”

It is Amis’s sensitivity to language which allows him to describe the different sounds so precisely. Language is a common theme in Amis’s non-fiction because he knows that attention towards language is attention towards the world. His style, bolstered by Latinate and literary diction, doesn’t allow the reader to become complacent, to turn her gaze from the subject, to let her mind wander. It is in care of language, not in political opinions, Martin resembles his father Kingsley. How fitting, then, that Amis Jr. includes the foreword he wrote for The King’s English, Amis Sr.’s guide to the English language, as a loving postscript to the portrait he gave us of his father in Experience.

As Kingsley did, Martin knows the value of humour. Not the value of jokes, which rarely have value, but humour: what Clive James called common sense dancing. Humour is the expression of rationality and sense, and Amis’s harshest criticism of Jeremy Corbyn is that he is humourless. As Amis wrote of another opponent, by impugning Corbyn’s sense of humour, he is impugning Corbyn’s seriousness.

At the 2011 Republic Party convention in Iowa, Amis describes the presidential election as between the bowel of America (the Republican Party) and the brain of America (the Democratic Party), stating that the developed world long ago chose the brain, and that only in America does the bowel continue to gain votes. Was 2011 so long ago? Amis includes an essay written in 2016 about presidential candidate Donald Trump, but doesn’t include one on Hilary Clinton, missing the opportunity to revise his statement: the 2016 presidential election was not a contest between bowel and brain but rather a grumbling match between two antagonistic bowels.

The 2016 presidential election was so ugly, petulant, and depraved, because many of the combatants failed to do what Amis does well: separate the person from the argument. In literary criticism, part of this is separating the man from the work. Amis shows this acute critical sense in essays on Philip Larkin, John Updike, and J.G. Ballard. While Ballard the man, Amis notes, feared global warming, Ballard the novelist thrived on ecological disaster: “he loves the glutinous jungles of The Drowned World and the tindery deserts of The Drought.” The fine balance of the phrase – with “glutinous jungles” matching “tindery deserts” syllable-for-syllable – combined with its trenchant observation showcases a critic of great value.

The essays on Princess Diana gave me less. While showing me the softer side of a hard-headed critic, these essays lack the piquancy which characterises Amis’s best work. Amis gives that to the other princess in the collection: Chloe, the porno princess of Los Angeles, whom he treats with sympathy, and makes the reader do so too, the latter of which he did less successfully when writing about Diana. Diana was probably too glamorous, just as most of Europe is. America has its glamour, too, but lacks a monarchy, castles, and the manicured world of Jane Austen’s novels. Perhaps it is best to view Amis as a miner: deep underground, in the narrow tunnels and cramped caves, among the labour and the coughing and the dirt, he finds gold

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025