Review: Degas: A Passion for Perfection

Olivia Hewes argues that Degas: A Passion for Perfection goes above and beyond most exhibition shows by situating Degas in his context, showing not just the art but the man himself

I wasn’t exactly sure what I was expecting from Degas: A Passion for Perfection, the newly opened exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

My expectation, I think, was a room full of a few of Degas’ paintings from the museum’s collection, alongside maybe a couple of star exhibits on loan from elsewhere. In fact, the exhibition spans seemingly all of the available rooms in the museum, and is an extensive and in-depth look at Degas’ art and the relationships that shaped his style. I have to admit, I did have difficulty just finding the main exhibition – there are a couple of smaller displays with relatively tenuous connections with Degas in neighbouring rooms, which were underwhelming to come across when I was expecting the art of the man himself. But eventually, after some serious searching, I managed to find it. There wasn’t really any clear direction to the exhibition, and it wasn’t evident how everything was arranged, so some sort of guidance in that sense would have been appreciated. Once you get over that, though, the exhibition really comes into its own.

“It completely altered my understanding of Degas as a man and as an artist”

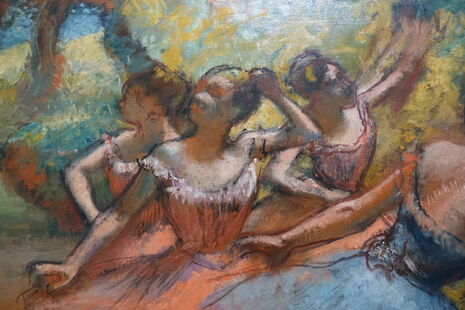

I will happily make the claim that it completely altered my understanding of Degas as a man and as an artist. I didn’t realise how little I knew about Degas before the exhibition. I thought of him, as I expect many do, as the impressionist painter and sculptor who eschewed conventional techniques to convey the movement of dancers with whom he was seemingly preoccupied. What this exhibition most clearly illustrates, however, is the way in which Degas almost obsessively copied and drew inspiration from the works of other artists, both contemporaries and old masters. The influences, both direct and indirect, which shaped Degas’ work were emphasised repeatedly throughout the exhibition.

In a way, the name is misleading. Although the focus was, of course, on Degas, he was situated so much in the context of those around him as to occasionally obscure the role of the man himself. Indeed, sometimes it did feel as if there was too much work by other artists which seemingly had little or no connection to the main premise of the exhibition, such as a large painting by Vanessa Bell of John Maynard Keynes and his lover right at the exhibit’s entrance. But this is at least better than the more common fault of museum exhibitions, which includes simply placing all available artworks by an artist in a room with no explanation of context or influences.

The range of work by Degas on display was truly amazing; it was interesting to see how the development of his styles challenged my preconceived notions of his work. There were some beautifully delicate pencil studies, which were compared with the incredibly detailed work of Ingres that had actually come from Degas’ own collection. These were displayed not far from some dramatic watercolour landscapes, showing the versatility and originality of the artist. If you were hoping for some classic Degas, in the form of sensitive observations of human encounters, in particular those of women, you won’t be disappointed.

The collection of paintings which formed part of the At the Café series were very much the Degas that I was expecting to see. The famous ‘little dancer aged fourteen’ makes an appearance, and there is due consideration of Degas’ sculptures, whose absence would definitely have been felt. The connections drawn by the exhibit’s curation between Degas’ dancers and the classical forms of, for example, ancient Greek tanagras were truly enlightening, and definitely encouraged you to develop a deeper understanding of his artistic processes.

In short, this exhibition really does serve to broaden the audiences understanding of Degas and his work. The wide range and variety of Degas’ own work, and the careful curation, by placing relevant artworks together, clearly suggested his versatility, and the many influences that shaped his art. A Passion for Perfection placed Degas himself in his contemporary context, as well as placing his most famous work in the context of his own wider artistic repertoire. It also showed how his was the work of a man who was constantly experimenting, and emphasised how, despite what we may assume, Degas was always changing himself

Degas: A Passion for Perfection at the Fitzwilliam, 3rd October - 24th January, Tue-Sat 10am-5pm, Sun 12-5pm, free entry

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025