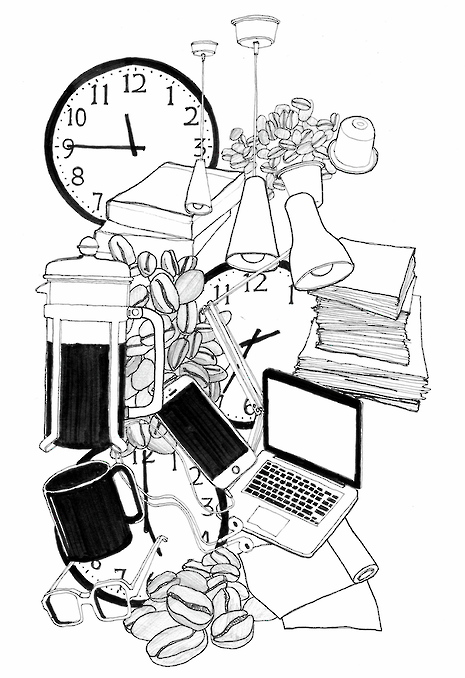

Deromanticising destructive work habits

In a university full of all-nighters and coffee addiction, Chloe Hadavas questions why we romanticise unhealthy work habits

On Thursday, I started this article with apprehension, knowing full well that I’d be writing it during my busiest time of the week: a sweet spot between a Friday supervision and Monday seminars. Since time management has long escaped me, I can see myself still writing into the early Monday hours despite an impending 9am class.

Like many uni students, I stumbled into an unhealthy work ethos over a period of years. My first taste of the all-nighter was the final essay of my first year, for which I managed to get a good grade in spite of the fact that I didn’t start writing, or even planning, until 10pm the evening before. The coffee-fuelled all-nighter soon became a trick I could pull out whenever I found myself in a time-strapped situation of my own making. Yet it wasn’t until my third year abroad at Cambridge that this mindset fully manifested itself. As a visiting history student, I wrote every single weekly essay, without exception, overnight.

"To the outsider, your academic achievement appears almost effortless when you’re pulling a Rumpelstiltskin, managing to spin last-minute gold while others are sleeping"

Given the normalisation here of sleep deprivation and rogue working hours, it’s perhaps fitting that my destructive study habits spiralled in my year abroad. In that year, I also witnessed something I had come across only sparingly before: a culture of peacocking about just how little work you’ve done. Appearing to put in meagre effort while achieving good results was the key to success in its most socially acceptable form. At the same time, flippantly mentioning the pressure you’re under played a substantial part in normalising daily struggle. Part and parcel of this culture, somewhat contradictorily, was the fetishism of the all-nighter. To the outsider, your academic achievement appears almost effortless when you’re pulling a Rumpelstiltskin, managing to spin last-minute gold while others are sleeping.

Such a generalisation of Cambridge’s culture oversimplifies an institution that varies among its departments, disciplines, degree programs, and colleges—but it’s still a generalisation that many students will probably recognise. It’s also something symptomatic of ‘elite’ institutions more broadly. At the University of Chicago, where I completed my undergrad, there’s the same tendency to work to the point of exhaustion, and even breakdown, but under a different guise: a monastic, frown line–inducing, 24-hour-library-oriented one, where students are under constant pressure to wallow and posture about the amount of work they’re doing at all hours. (Students have even written about being chastised by their peers for leaving the library early and taking both Friday and Saturday evenings off.)

The fact that normalising sleep deprivation and irregular hours is harmful should go without saying. Recent studies have shown that less than eight hours of sleep a night is deleterious to both short-term and long-term health, and anyone who has sacrificed sleep for schoolwork is familiar with the resulting irritability and susceptibility to illness. And the physical strains go hand in hand with the mental ones: according to the 2015 National Students Survey, only 37% of Cambridge students feel that their course ‘does not apply unnecessary pressure’. Despite these well-known effects, unhealthy habits maintain their allure. For me, at least, producing good work on little sleep has induced euphoria, but with the delayed cost of subsequent self-loathing and long periods of sleep on ‘off-days.’

More generally, we romanticise these habits as part of the creative process, often idealising artists and writers who produce in manic bouts of inspiration. Though this may not have much bearing on how we conceive of daily work, it’s tied to the idea that creative life and academia exist beyond the strictures of normal professional life. I’ve felt this on a personal level, especially as a student of the humanities and social sciences. Sometimes when I sit down at a desk in the early morning in preparation for a day of studying and research, I start to feel a sense of dread that I might be giving way to the Protestant work ethic I’ve been almost conditioned to disdain, clinging instead to notions of inspiration over productivity. This may be the ultimate procrastination technique. It’s as if I’ve tricked myself into giving in to laziness in the name of shunning the work-life balance, waiting until the last possible moment to produce something ‘authentic.’

In my experience, and in the experience of friends who share similar troubles, this mindset fostered at university does not tend to produce works of artistic genius, but rather habits and patterns of thought that are harmful to one’s wellbeing. As an MPhil student, I still struggle in this cycle, especially given the self-directed nature of a research-oriented degree. Even so, I am finding a sense of quiet comfort on those days I can deromanticise the outlook I’ve cultivated over the past few years and recover the routines and structures I once shed

Illustrated by Jeffrey Chu