Theatre in translation: To the ends of language

Columnist Margaux Emmanuel discusses the inherently complex nature of translating theatre.

A few years ago, I listened to Ladislas Chollat discuss adapting Florian Zeller’s play Le Père, for the Japanese stage – without speaking Japanese. I remember him admitting how it was mostly through a process of trial and error with his translator; if the actors around him didn’t laugh when he would have expected them to do so, he knew that something was wrong. This example clearly shows that translating theatre is a hefty task, surpassing the mere translation of units of semes and syntax.

In retrospect, the translator’s role was probably the most crucial in this performance; his task wasn’t transactional, giving a mere equivalent of a term to convey meaning, but he had to recreate an impression through language. Language becomes the principal actor on stage, whilst the translator is the vector of the performance. The director was completely relying on his translator to understand the implications of every written word. In theatre, the notion of translational accuracy shifts; conveying meaning is not enough – the translator needs to convey life.

“Cultural implications mustn’t be forgotten either, as they are central to the recreation of this dramatic impact”

Actors Christophe Brault and Jean-Paul Dias once said “We are extremely exposed, almost naked. We exist exclusively via language, we can’t cling onto anything else’ in the French première of Par les routes by Noëlle Renaude (Cristina Marinetti and Manuela Perteghella Roger Baines in “Staging and Performing Translation”). The translator becomes responsible for the theatricality of the play, surpassing the plot and characters – it cannot simply “make sense” or, in the case of prose and verse translations, recreate an equivalent. The theatrical work strives for performability; the director needs to be able to interpret the work in the way he wishes, yet to call Romeo and Juliet “Romeo and Juliet”, there needs to be a binding element in the language itself.

Theatrical performance bases itself on the malleability of the written text – whether it is Romeo and Juliet performed at the Royal Shakespeare Company, on a stage in Spain, in the desert or in space, the play remains Romeo and Juliet – there is still a flexible, yet existent, tacit pact between the director and the original work. The work needs to be recognizable, and needs to be in line with a tradition of performances, especially for canonical works like Shakespeare’s. But can “Wherefore art thou Romeo” be performed the same as “Pourquoi es-tu Roméo”, or “Oh Romeo Romeo ¿dónde estás?”? Will the dramatic impact be the same? Is the meaning the same?

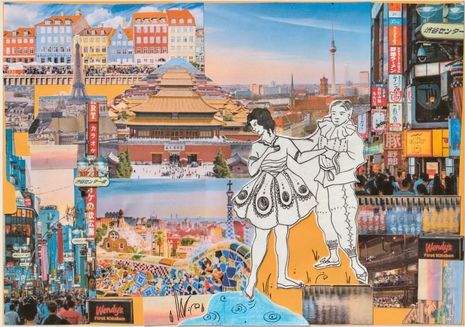

Cultural implications mustn’t be forgotten either, as they are central to the recreation of this dramatic impact; whether it be in China, Germany or England, it doesn’t have the same meaning. The initial example of Ladislas Chollats’ difficulty at translating jokes clearly shows that the dramatic performance’s pretension of ‘recreating life’ can sometimes be unconvincing, or it is not simply performativity for the sake of performativity, but also managing to recreate a compelling performance for the new audience.

“Perhaps language isn’t a barrier, but gives us the perfect space and occasion to innovate and defy borders.”

The issue is similar in any written work, and famously, poetry – would Edgar Allan Poe have grimaced at Baudelaire’s translation of his works? Hemingway would have certainly been shocked if he had read the controversial French translation by Jean Dutourd of The Old Man and the Sea. Yet theatre goes even further – it needs to give life. The issue of translating theatre pulls at the thread of linguistics, but also of language as a means of existing – it can seem as if a moment in one language cannot be recreated in another. We cannot consider theatre as an art form for isolated phenomena. But viewing language as hermetic would be incorrect, as well as reductive. Perhaps language isn’t a barrier, but gives us the perfect space and occasion to innovate and defy borders.

A few years back, The Grønnegård Teatre in Copenhagen, Denmark produced Twelfth Night in Old Danish. The linguistic approach of having translated the actual text to not only Danish, but Old Danish was particularly intriguing. There was obviously an attempt to recreate the relation of the Anglophone audience to Shakespeare, with the Danish audience. Translating Twelfth Night to modern Danish just wouldn’t ring right.

Translating theatre is therefore also recreating an experience. If we speak a lot about texts being “lost in translation”, we must also lose ourselves in the translation, taking a dip into another culture, in another time that also becomes ours.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025