Lungs: a play about the Big Questions but without answers

Joshua Robey reviews Duncan Macmillan’s Lungs, live-streamed in June 2020 as part of the Old Vic’s In Camera series and streamed as a pre-recorded performance in January 2021.

‘Ten thousand tonnes of CO2. That’s the weight of the Eiffel Tower. I’d be giving birth to the Eiffel Tower.’ This comic observation is typical of Duncan Macmillan’s Lungs, a dazzling and affecting – if somewhat frustrating – play, in which an unnamed man and woman negotiate starting a family in a changing world. The play begins with an ambush in an IKEA, when he asks her if they should consider have a baby together. This magnifies existing fractures in their relationship and they quickly turn to discussing the moral and social responsibilities of raising a child amid the climate crisis.

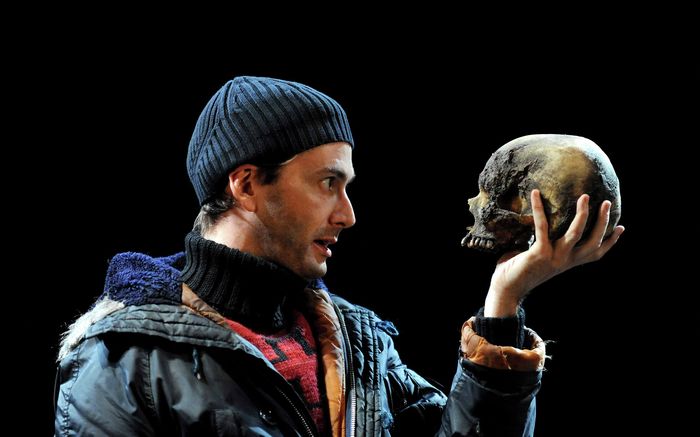

The play’s dialogue has a brittle quality that takes a few minutes to get used to, its rhythm that of a heightened theatrical naturalism – where sentences rarely find endings apart from in regular witty punchlines. The cast do well with the material’s slight falseness. Matt Smith is particularly comic when delivering his lines rapidly, but even more intriguing as a performer when his character holds back, unsure of quite what to say. Claire Foy is excellent also, especially in the play’s most tragic moments where her character turns bitter and spiteful.

The play appears to be setting up an environmental debate as its central quandary, exemplified in the measuring of a human life against the future emissions they’ll cause. Yet Macmillan doesn’t actually seem interested in debating this subject. After all, the true environmental aim would be reducing carbon emissions per person until a human life is carbon neutral – zero Eiffel Towers. Even more importantly, any workable solution for sustaining human life inherently requires the birth of more humans. Lungs avoids working through the manifold complexities of such a debate. Instead, it implicitly asks whether it is fair to make a child live in a potentially unliveable world. Yet even this masks a deeper anxiety over their capacity to be good parents to their prospective offspring, and whether they are good enough in general.

“Worrying about the environment is really just cover for their anxiety over whether they are good people.”

Macmillan places environmentalism at heart of his characters’ identities – part of their liberal credentials, though in a way that is entirely passive. ‘We recycle’ becomes an empty refrain, desperately substantiating the claim that they are ‘good people’ – as does their insistence: ‘We give to charity.’ Long pause. ‘Don’t we?’ Worrying about the environment is really just cover for their anxiety over whether they are good people. That they worry itself is a sort of substitute activism; their passive care is proof of their goodness and negates the need to actually act.

For most of the play, Lungs is frustratingly uncertain in whether it wants to satirise its characters for this or make us sympathise with them. It succeeds to some extent in doing both, becoming genuinely affecting at times. I’ve seen this staging twice now, both times in lockdown; first livestreamed last June, and then again, in a recorded version, at the end of January. Curiously, although the Zoom stream was identical for both performances, I did feel a sense of ‘liveness’ in the play last year that was missing on a second viewing. Perhaps it was the sense of connection achieved by audience and performers convening at the same time, but the play struck me as far more emotionally charged last year.

The Zoom format suits the play surprisingly well. The text requires no props or scene markers, and under Old Vic Artistic Director Matthew Warchus’ direction the scenes flow freely into each other. The transitions are sometimes denoted by the actors changing position, sometimes it’s a just a slight mid-line change of tone.

“For most of the play, Lungs is frustratingly uncertain in whether it wants to satirise its characters for this or make us sympathise with them.”

The split-screen, socially distanced format becomes devastating at times. Subtle additions to the script (‘Why are you standing so far away from me’) only add to the tender presentation of the trauma of miscarriage, and subsequent relationship breakdown. The distance only highlights the ways the couple cannot quite connect, and the performances are at their best when reflecting the difficulties caused not by climate change but the occasionally bleak turns of everyday life.

Especially moving on my first watch was the play’s ending, a dizzying acceleration in pace compressing the rest of the characters’ lives into a bravura two-minute sequence. They wave their child off at the school gates. His memory starts to go. They think about finding a home. His half of the split screen fades to black.

Yet as satisfying as Macmillan’s gently realistic happy-ever-after ending is, it confirms the tentative optimism that underscores the piece: everything will be fine if we just focus on the positives. Their child grows up and they grow old, and although climate change is understood and debated by the characters in great detail, it isn’t something they ever seem to feel acutely. In the end, the solution is just to stop watching the news. In her final monologue, Foy bleakly tells us that ‘Everything’s covered in ash’, but despite this there’s still ‘fresh air’ to be found in central London.

Lungs is one of relatively few ‘climate crisis’ plays to have met a large audience, though to categorise it as such misses its true concerns. Thinking about climate change is only one way the characters think about their own anxieties over their relative goodness as people, their mortality, and their fitness for parenthood. As a play about the climate crisis, it feels incomplete. Yet as an emotional character drama (especially one watched during another global crisis), Macmillan gives us a perhaps valuable sense of comfort, that it will all be all right in the end.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025