End of the Line preview

This Painstakingly crafted production promises to be a beautifully immersive experience writes Andre Kaljevic

Will Johnston-Wood’s ‘End of the Line’ is an unusual piece of theatre. It is as much about the dangers of automated processes and their potential to wipe out administrative roles, namely the manual telephone exchange of the sixties, as it is about the humanity that is lost with such innovation. Set in 1969, the play is about operators and the process of replacing them with the mechanised system that we now have.

"how does one make something as seemingly mundane as a call centre into a theatrical showpiece?"

It is a painstakingly wrought production, Johnston-Wood has carefully planned the play’s staging, the exchange room is a three-dimensional structure that encircles the audience, making for a truly ‘surround sound’ production. He describes ‘setting and staging’ as the things that he would like to most get across to people, and then ‘the thematic stuff around that’. The central set is a switchboard with an operator, its main character, called Susan Lawrence, whose task it is to connect calls within the building. Johnston-Wood says that ‘All the staff come in to make calls and get connected, except, when they have a call to make, rather than walking in on the centre of the stage, they’ll walk maybe in the stalls somewhere’. This sense of characters not just performing in front of an audience, but being at one with the audience, induces the play with a sense of hyper-realism. The audience are complicit in the main characters’ actions, literally eavesdropping on other people’s conversations. In his research for the play, Johnston-Wood read anecdotal stories of women who were operators; their roles were to create a circuit: someone would ring them connecting the two together, they would then ring the other person on another circuit and if they answered, the operator would put a cable across and connect the two together. What this also meant however, was that the operators themselves had to pull out, but of course, they didn’t always do that, and listened in on conversations. In a sense then, as an audience, we too are cast as those operators.

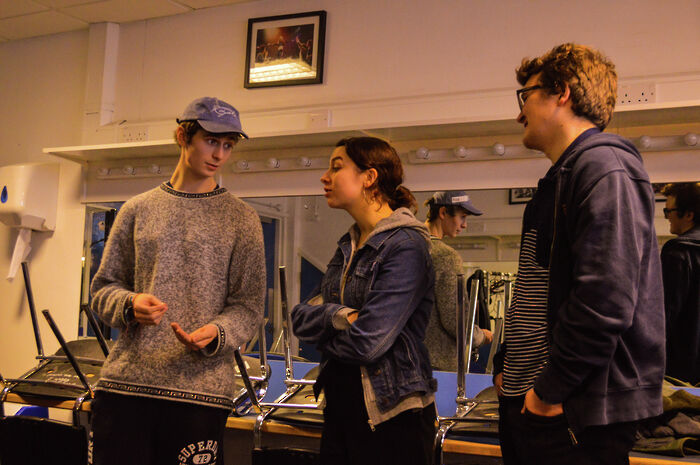

The characters too, are intricately thought out personalities. Rowan Gow’s Mr. Max Askew plays head honcho, or ‘head of personnel’, of a human resources team that is tasked with gradually phasing out the national operation of phone operators. He comes off as believable and more importantly, likable, despite his veering on the inhumane job specification. Izzy Collie-Cousins’s Mary is the engineer who is responsible for putting all the automated switchboards in the GPO. Coming straight off the back of an engineering apprenticeship, she knows much about her specialty but less about the old system. She joins the team pretending to be a trainee phone operator for a few days to get to grips with the way the non-automated system works so that she can effectively upgrade it. She is complicit in what Izzy describes as ‘Susan’s (played by Emily Webster) messing things up’ because she is privy to all that she enacts on her unsuspecting employees. Emily describes her character as ‘clutching at straws, just trying to delay it all as long as possible, she’s not being all that realistic’. Susan clings to preservation, she is not happy about the fact that she has to connect all these calls, issuing redundancies. Mary comparatively, is absolutely keen to push on with the phasing out of redundant technologies, given that there is the possibility to upgrade the existing infrastructure. The two come from very different mindsets, Izzy says that ‘Mary has to learn about the human cost whereas Susan is that human cost’. The two describe the most challenging scenes to perform as being those ‘where there are nine characters on stage, all having separate conversations, and nobody’s allowed to make eye contact’.

This is a play where context matters a lot, and the manual telephone exchange is not the first relic that comes to mind when one thinks of the swinging sixties. Moreover, how does one make something as seemingly mundane as a call centre into a theatrical showpiece? I wasn’t quite sure of how to answer that question myself, but after reading Johnston-Wood’s script I was thoroughly won over. As a result of the perhaps clinical setting of the play, the onus is on the cast and staging to bring the proverbial switchboard to life. Thankfully, ‘End of the Line’ does this in spades. Right from the start, the back-and-forth dialogue creates a frenzied excitement as we jump from line to line, consuming all the drama at what feels like light speed. ‘What sympathy! And don’t you know all the gossip…?’ says Graham merely a few lines in, plugging us in, as an audience, to the switchboard of gossip that permeates the fabric of the play. Why should people see it? Well, the play is immersive. Characters deliver monologues from the middle of the audience, there many memorable lines in the play, ‘Crabs like to climb up drainpipes backward with margarine’, sticks out in particular. I contemplated whether or not to open this preview with it. But if there is one take-home point, it is that this is a play that literally immerses us its world, and as such, we don’t just watch its story unfold, we’re surrounded by it.

Features / Meet the Cambridge students whose names live up to their degree9 September 2025

Features / Meet the Cambridge students whose names live up to their degree9 September 2025 News / Student group condemns Biomedical Campus for ‘endorsing pseudoscience’10 September 2025

News / Student group condemns Biomedical Campus for ‘endorsing pseudoscience’10 September 2025 News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025

News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025 News / New left-wing student society claims Corbyn support11 September 2025

News / New left-wing student society claims Corbyn support11 September 2025 Science / Who gets to stay cool in Cambridge?7 September 2025

Science / Who gets to stay cool in Cambridge?7 September 2025