The History Boys review

The History Boys is a delightfully realised comedy that resonates many years after its 1980s setting

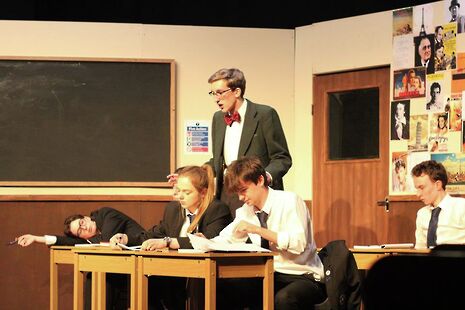

“How do I define history?” says student Rudge (Charlie Morrell-Brown): “It's just one fucking thing after another.” The History Boys, performed at the ADC now fifteen years after its conception, might now similarly be defined as a history, of sorts, but this vibrantly realized revival was far from plodding. Brightly enhanced by a skilled cast, the play is a manifestation of part-academia, part-banter, and overall modernly resonant relish.

The History Boys presents a class of students in the eighties, post-A levels but pre-University acceptances, preparing for Oxford and Cambridge entrance examinations. Facilitating their preparation are a quartet of disparate academic figures-- the eccentric and anti-institutionalist Hector (Tom Nunan), the young divergent Irwin (Oliver Jones), an excessively achievement-obsessed headmaster (Eduardo Strike), and the softly, yet heartily wise Mrs Lintott (Ella Blackburn), the only female character.

The play is a focused dissection of education-- from methods of learning, to where this learning may lead and later manifest-- masqued behind a constant peppering of comedic banter to lighten the (often unrelenting) intellectual whirlwind.

And the dialogue, certainly, is unceasing, often prolongedly so. Though layered with comic respite, the intellectual punch after punch of bant and quip often seemed long-enduring, and though the pacing was natural, it may have profited from slightly enhanced speed.

The Oxbridge focus resonated particularly for the Cambridge audience, spurring larger, referential (and often self-deprecating) laughs, and contrarily, poignant moments of self-reflection, harkening back to perhaps similar personal pre-collegiate journeys.

Each character is delightfully manifested by a superb cast, embodying each distinct intellectual with a different performative flair. There’s the scholarly jesters, like Lockwood (Harry Camp) or Timms (Tom Baarda), the more subdued, yet equally spirited Posner (James Coe), or the brooding yet droll, Dakin (Matthew Paul).

Strike’s performance as the obtuse headmaster is comedically splendid, his blazing focus on Oxbridge results entirely over-the-top, but to an audience, welcomingly so. And Jones’s Irwin, more opposingly subdued, delivers focused, pointed characterization of an emotionally troubled teacher in a similarly explorative phase as his own protegées.

"In the #metoo era, Hector’s character becomes not so easily forgivable”

Nunan as Hector was a certain highlight-- from his physicalized form, walking with a weighted, bent-over gait-- to his overt charisma, juxtapositionally paired with clear guilt from his misbehaviours with his students.

Director Patrick Wilson approached the long-lauded and often-performed play largely classically, whilst still allowing space for more modern themes to permeate the eighties landscape and be readily explored.

The foundation of the narrative overtly sympathizes for Hector as a flawed, yet vibrant and well-liked educator-- however, in the #metoo era, Hector’s character becomes not so easily forgivable. Moments of prolonged, weighted silences and heightened sombre overtones present the teacher’s malactions with a defined gravity, and not so easily dismissed, despite his dynamism.

And in contrast, Mrs Lintott’s impassioned speeches resonate profoundly. Her focused monologues on history from a wanting feminine perspective --“history is a commentary on the various and continuing incapabilities of men”-- and her blunt dismissal of any justification for Hector’s misbehaviour focus the narrative in the present and progressive, heeded by Blackburn’s resolute delivery.

And among the collection of ‘history boys’ are, distinctively, two history girls-- one of the play’s more central narrators, Scripps, portrayed by Ellie Gaunt, and student Crowther, by Hannah Lyall. Though these actors still portray characters defined as male, female students are a welcome sight within the overtly masculine dynamic, making for compelling unromanticized male-female relationships and a threshold to explicitly examine the overt gender stereotypes of the drama.

At times, the play seemed a bit bizarrely lit, overhead fluorescents often glaringly bright for softer scenes, or a simple spot perhaps too focused for a casual inner soliloquy.

Though first staged 15 years ago, and set nearly four decades prior to today, this iteration of The History Boys proves as moving as ever, and particularly pertinent through a modern contextualization. Though narratively saturated with academia, perhaps unwelcome outside the lecture hall, never fear: the play is, overall, a comedic pleasure.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026