Relocation, relocation, relocation: ‘Taking liberties with a play’s temporal dimensions is problematic’

“Give me my historically-accurate plays over relocated performances any day,” writes Joe Maron on theatre’s post-modern pandemic of re-setting classics

I can’t remember the last time I saw either an Elizabethan or a Jacobean play staged in its original temporal setting. Gregariously oversized fan collars, swollen codpieces and those wonderfully voluptuous plus four-like contraptions that Philip Sidney always liked to be pictured in, seem to have been exiled from the modern stage.

I’m sure they still make appearances now and then, of course, like some senile and vaguely embarrassing old aunt who spends much of the year in a retirement home, but gets wheeled out for the occasional birthday. Yes, period pieces seem to have been sidelined in recent years, but it’s time that we should see them back on the court.

My call for more historically faithful productions, however, is the function of more than a love of Renaissance costumes. Taking liberties with a play’s temporal dimensions is problematic, from an ethical as well as an aesthetic perspective. Relocating plays in time almost inevitably invests them with political meanings they would not have possessed in their original contexts of performance and which their playwright could not possibly have intended.

Now, this isn’t necessarily a problem when the playwright in question is a relatively small fry, but when a director adds extra political dimension to the work of somebody of great note and position in the canon, say Shakespeare, then ethically, things begin to get a bit fuzzy. Shakespeare is, whether we like it not, a figure of great cultural weight.

“Relocating classics isn’t just suspect on the grounds of morality, it also, depressingly often, produces bad drama”

His is a household name comparable only to a few others, and his widely-accepted genius, and therefore authority, means that if his name gets attached to something – a particular set of views, for example – that something is in some way legitimised. When journalists went around interviewing dons last year about the bard’s attitudes to multinationalism, they were seeking to co-opt him for a political cause. Re-staging plays is often no different. And I take ethical issue with this, as I would some hope some of you reading would too.

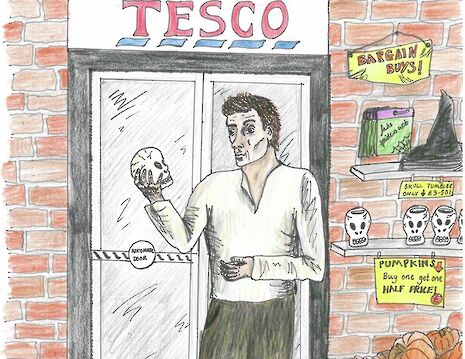

But relocating classics isn’t just suspect on the grounds of morality, it also, depressingly often, produces bad drama. Take this year’s RSC production of Titus Andronicus, for example. Lauded as “chillingly contemporary”, but like so many performances that opt to modernise a Renaissance play, this one only succeeded in eviscerating its aesthetic power.

The decision to replace Shakespeare’s swords with modern hand guns robbed the violence of most of its intimacy, oh so important in these kind of Senecan-inspired revenge dramas. Titus’s early slaughter of Mutius, for instance, is a personal, close-quarter encounter, reflecting their genealogical closeness – Mutius being, of course, Titus’s son. The emphasis on both these proximities is responsible for much of the moment’s pathos and this was lost when Titus instead just blasted him callously away with a pistol.

The substitution of guns also fared badly in the climactic Thyestean banquet. The deaths all felt rushed and the whole thing was over too quickly – what should have been an orgy of gore barely even registered. Evocations of contemporary gun crime in America, or no evocations of contemporary gun crime in America, the modernisation was an aesthetic damp squib.

“Most serial theatre-goers tend not to be lacking in nous – they don’t need a play’s resonances to be spelled out to them through a re-setting”

Productions that shunt plays forward in time also often come across as patronising. Think about it, what so-and-so-director is basically saying when they decide to re-set a play and thus tie its action up with a particular period and its politics, is that they don’t think their audience capable of figuring out the parallels for themselves.

Most serial theatre-goers tend not to be lacking in nous – they don’t need a play’s resonances to be spelled out to them through a re-setting. They can speculate about contemporary relevance on their own. Worse still, in their eagerness to ensure that their temporal and political pyrotechnics get noticed, relocated plays evince an unfortunate tendency toward hyperbole.

Overly conspicuous sets, stiflingly large numbers of props, these seem to be the inevitable corollary to a relocated script. The result is without fail a claggy, ocularly clotted performance, in which the best parts of the original plays of Shakespeare and his contemporaries find themselves obscured by the extra baggage.

No, give me my historically-accurate plays over relocated performances any day. They help skewer myths about the timelessness of art, and above all else, remain faithful to the playwright’s original conceptions

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025