France 4-1 Algeria, October 6th 2001: The Dangers Of Politicising Football

This week Liam Elliott Brady evaluates football’s political role and potential. Through focussing on France’s 2001 clash with Algeria, Liam shows how this role should not be overestimated.

During the summer of 1998, it is said that the colours of the French tricolore were not red, white and blue. Rather, driven by the triumph of an inspired multicultural World Cup team, they had morphed to become black, blanc and beur (black, white and Arab).

Arguably, this slogan helped reshape the French national identity: it represented a spirit of diversity and inclusivity upon which a new, more tolerant France would build its success.

Indeed, there did seem to be a noticeable improvement in race relations following the 1998 tournament. Throughout the 1990s, France had been rife with Islamophobia: a 1990 Le Monde survey found that 76% of French people felt that there were too many Muslims in France, while 39% felt an “aversion” towards Muslims.

In 1996, France recorded the highest annual number of terrorist incidents to date (270), the majority of which were attributed to radical Islamist groups. Such attacks engendered a widespread suspicion of North African immigrant communities, which manifested itself in a sharp rise in acts of violence against these groups. The far right capitalised on this wave of xenophobia and in 1997 the National Front won their highest ever share of the vote in a National Assembly election (14.9%). Before 1998, France had been disunited, despondent, and in disarray.

The story of the French national team between 1998 and 2001 forces us to reconsider the political significance of football.

However, the overwhelming presence of players from immigrant backgrounds in the World Cup team gave optimists hope that football could be used to heal a bitterly divided society. Ghanaian-born Marcel Desailly, for instance, led an ironclad back line, while Christian Karembeu, raised in New Caledonia and an outspoken critic of the government’s repression of ex-colonies, started the final in midfield.

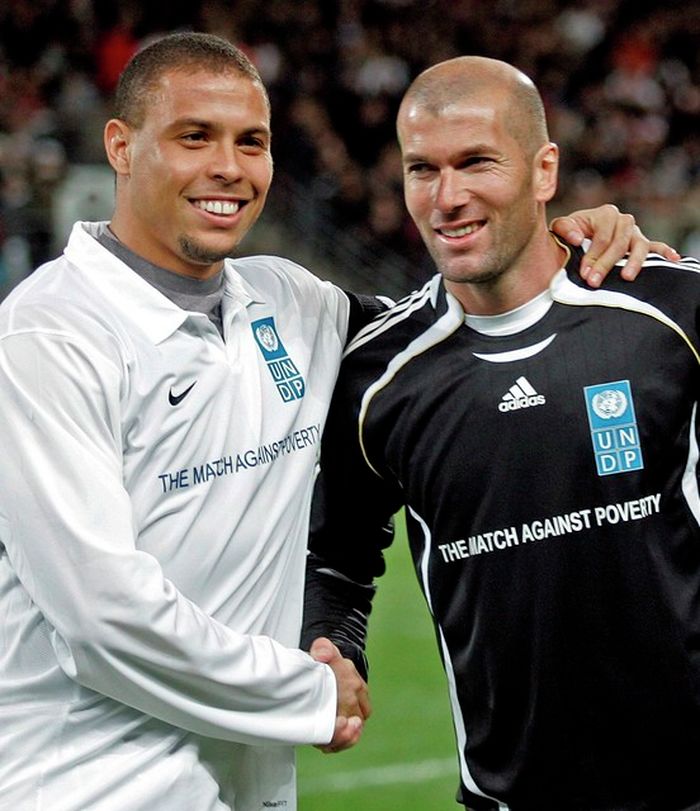

Perhaps most notably, Zinedine Zidane, whose parents emigrated from Algeria to Marseille, was instrumental in France’s attacking set-up, and was subsequently named player of the tournament. France’s ‘rainbow-team’ had come to represent a microcosm of a model multiracial society.

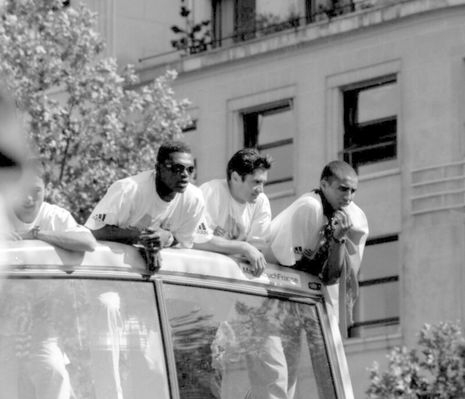

Across France, the team’s World Cup triumph was celebrated as a victory for multiculturalism. On the night of the final, Zidane Président was projected onto the Arc de Triomphe, as cars honked their horns en masse to the rhythm of the Marseillaise. At least superficially, France had entered a post-racism age of unity.

Nevertheless, beyond this, nothing much appeared to change. Unemployment rates among ethnic minority groups were as high as ever and racist hate crimes persisted, as immigrant communities continued to bear the brunt of systemic problems in French society. After all, it would be unreasonable to expect a sporting event to right the wrongs of France’s ugly colonial past.

Among fans, there was a striking sense of anger. Among players, there was a serious fear for their safety.

Among those most adversely affected by France’s colonisation were French-Algerians. Having only been liberated in 1962 following a destructive eight-year Civil War, colonialism was fresh in the Algerian collective memory. Despite this, Zidane’s role in France’s national team left many French-Algerians feeling a sense of pride and embracing the French national identity.

Unfortunately, it was this enthusiasm that France’s politicians would exploit by arranging a now infamous match against Algeria in 2001. After meeting with his Algerian counterpart, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, in 2000, French President Jacques Chirac agreed to hold the first ever international friendly between the two sides on October 6th the following year.

From its inception, this match was seen as a political spectacle, a tool to make ground in opinion polls. It was clear that no thought had been put into the safety of the spectators or the players.

What the organisers failed to understand was that the match would be played against an incredibly politically volatile backdrop. To French-Algerians, October 6th is a date which holds a great deal of historical significance: on October 6th, 1961, French Chief of Police Maurice Papon established a highly restrictive curfew for anyone of Algerian descent living in Paris’ suburbs. Thus, to hold the match on a date which represented a long history of discrimination to so many Algeria supporters was not only insensitive, but also ran the risk of causing civil unrest.

Alongside this, just two weeks earlier, the explosion of a chemical factory in Toulouse was wrongly attributed to an Islamist group. This shed light on the institutional racism in French law enforcement, and disillusioned French Muslims.

Among fans, there was a striking sense of anger. Among players, there was a serious fear for their safety. As French defender Frank Leboeuf later recounted, “It was a mess, a shame for our country … we didn’t play a match of football, we played a political game for people who wanted to tell a story.”

As expected, the match was a tense affair. After 55 minutes, France were leading the visitors 4-1. However, technical brilliance from the likes of Thierry Henry and Robert Pires was overshadowed by the unnerving atmosphere in the stadium: agitated fans hurled verbal abuse at French players, as brawls broke out in the stands.

This tension culminated in the 77th minute, when a wave of fans invaded the pitch. Within minutes, the match was called off.

The publicity stunt had failed. Riots erupted across the Parisian banlieue as players and politicians alike denounced the fans’ behaviour. There appeared to be the expectation that Algerians would readily forget years of colonial oppression with one match of football. To them, this was insulting.

The France-Algeria debacle brought an abrupt end to a brief period during which football was seen as a vehicle for tolerance. Inter-racial tensions resurfaced, bringing racism back to the forefront of public consciousness. It became abundantly clear that the black-blanc-beur spirit was nothing more than an empty platitude. For the French national team, what followed was a series of scandals and spats among team-mates that defined an underwhelming decade.

The story of the French national team between 1998 and 2001 forces us to reconsider the political significance of football. While teams and players have been used as figureheads for important movements, they prove less effective when dealing with institutional problems like racism. As much as we may romanticise the power of football, it is sometimes important to remember its limitations.

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026 Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026

Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

![How to Create an Attractive Freelancer Portfolio [5 Tips & Examples]](https://www.varsity.co.uk/images/dyn/ecms/320/180/2026/02/vitaly-gariev-ho2tNOWZYXM-unsplash-scaled.jpg)