Endometriosis treatment: same old status quo?

Lizzie Grace explores what endometriosis treatment looks like now and how it could in the future

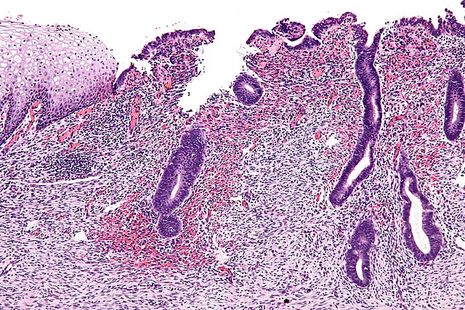

Media coverage of endometriosis shows a clear pattern. The disease, which manifests with uterus lining-like tissue growing elsewhere in the body, has for a long time suffered from a lack of viable treatments. Valuable but all-too-repetitive articles raise awareness of the severe pain, fatigue and infertility which affects 10% of all AFAB (assigned female at birth) individuals, costing the UK government £8.2 billion per year. The stark consequences of limited treatments, slow surgical diagnosis, and medical and societal gaslighting are repeatedly exposed through patient interviews.

Such reports are rapidly succeeded by the declaration that a ‘revolutionary’ treatment or test for endometriosis is available, or ‘just around the corner’. Unfortunately, the coveted blood test for endometriosis has been ‘just around the corner’ for over a decade, and ‘revolutionary’ treatments are usually just…different versions of hormonal contraception.

“Most experts blame chronic underinvestment in women’s health research”

Hence, my scepticism at the recent announcement of a new endometriosis pill, available on the NHS. Ryeqo combines relugolix, estradiol and norethisterone. In reverse order, norethisterone mimics progesterone, while estradiol is the strongest form of estrogen in our bodies. In medicine as in nature, these limit the release of luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), preventing egg development to suppress the menstrual cycle.

If this sounds like a combined oral contraceptive pill, that’s because so far, it is.

The difference is the addition of relugolix. This blocks the action of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH), which normally promotes FSH and LH release. Relugolix therefore enhances menstrual cycle suppression from a different direction, acting synergistically with the other components. Plus, as with other GnRH blocking drugs, ‘adding back’ estradiol is essential to limit the bone density loss and cardiovascular and cognitive diseases otherwise associated with long-term use.

However, GnRH blockers aren’t new: they’re commonly used as puberty blockers, as well as to treat hormone-responsive cancers, and infertility: they’ve been employed in endometriosis treatment for over twenty years. Indeed, menstrual cycle suppression has always been our main, non-surgical attempt at reducing symptoms. It’s only partially effective. Why, after sixty and twenty years respectively, are we still so dependent on these drugs?

“A common yet unconvincing argument is that endometriosis is just so complex”

A common yet unconvincing argument is that endometriosis is just so fantastically ‘complex’, affecting numerous organ systems, throughout the menstrual cycle. So do hypertension and diabetes, yet I’ve learnt multiple classes of diverse drugs for each of these conditions to survive my pharmacology exams. Labelling the female body as ‘complex’ provides a convenient excuse for our scientific and social failures, not least the ongoing exclusion of AFABs from clinical trials.

Consequently, most experts blame chronic underinvestment in women’s health research, of which medical misogyny is cause and effect. In an un-funny joke of a statistic, the US government spent five times more on erectile dysfunction drugs than endometriosis research throughout the 2010s.

Still, there is hope. AFAB health is receiving more funding and recognition than ever before. Within endometriosis research, the contribution of the immune system is drawing increasing attention: many signalling molecules implicated (for example interleukins and growth factors) are already targeted by organ transplant and autoimmune drugs, many of which are now undergoing pre-clinical testing for endometriosis.

Similarities between endometriosis and cancer (including metabolism, nerve and blood vessel growth, and cell type alterations) also invite drug repurposing, especially as the side-effects of cancer treatments are reduced.

Finally, platelets (pro-inflammatory, not-quite-cells) accumulate within endometriosis lesions and induce scar tissue formation (fibrosis). Anti-platelet drugs are used to prevent heart attacks and strokes, while drugs targeting lung fibrosis have proliferated since COVID-19.

Despite this array of pharmacological possibilities, drug repurposing remains a major theme. This highlights that endometriosis is a multi-systems disease, where the rapid deployment of effective treatments is, correctly, prioritised. However, it also demonstrates the unnecessary time lag in endometriosis research: if we understood the role of immune signalling, platelets and scar tissue in other diseases twenty, thirty, fifty years ago, why isn’t the same true for endometriosis?

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026

News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026 News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026

News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026