How much is too much?

In the second of a three part series for Varsity, Cambridge SU Ethical Affairs Campaign argues that if we want to take a stand against war, inequality and climate breakdown, we need to take the fight to Cambridge University, the richest higher education institution in the UK

As we explored in the first part of this series, the University of Cambridge continues to invest in exploitative and ecocidal industries, despite having ‘divested’ in 2020. But while we should certainly continue to challenge them in this area, divestment itself is just the start. A much larger and contentious issue has, so far, slipped through the cracks. Cambridge’s assets are not necessarily liquid — much of the University’s wealth is in the form of land. Oxbridge colleges own 126,000 acres of land in England, approximately 0.39% of the country.

The obvious question here is ‘why?’ What business does Christ’s College have with owning a small farm in rural Lincolnshire? Why does Darwin own the site of ‘Mobile Fone Experts’ in Ipswich? History plays a part — many of the old colleges have been large landowners for centuries — but it’s more than this. The conflation of land, a factor of production, with capital has been one of modern capitalism’s greatest achievements. It has enabled wealth hoarding on a massive scale — as the example of Cambridge illustrates.

Locally, the University of Cambridge owns a large proportion of the city and continues to buy up land, even though, as noted in April’s Environmental and Sustainability Strategy Committee meeting, the ‘ongoing growth of the estate’ is potentially responsible for the University’s comprehensive failure to meet its carbon reduction targets, missing targets in 12 out of 13 impact areas — reported in the most recent annual carbon report. Increasing emissions shouldn’t be our focus here. Cambridge is the most unequal city in the UK: the top 6% of earners in the city take home 19% of the total income generated, while the bottom 20% of the population account for just 2%. Homelessness is prevalent, and property is expensive. The average house price here sits at a staggering £471,562 compared to the UK Cities average of £254,600. The University, as one of the largest landowners of the city, plays a role in this — pricing local people out of the market in its pursuit of profit.

“The University continues to hoard wealth and perpetuate inequality within the city.”

Anecdotally, we’ve spoken to many residents who feel that the University’s stranglehold on the city is getting worse, with many areas increasingly privatised and public access denied. King’s College’s attempt to ban wild swimming at Grantchester Meadows in June — which failed due to the public outcry it prompted — is just one example of the enclosure that Cambridge and its Colleges are pursuing. Despite the incredible work of local charities and activist groups, the University continues to hoard wealth and perpetuate inequality within the city.

Despite its already astronomical wealth, the University still took out a £600 million bond in 2018 to take advantage of low interest rates. Like much of the University’s endowment, these bond proceeds are not being put to any particular use, as Reporter documents show, they are simply sitting there, reserved for ‘income-generating projects’.

Only a small proportion of the £600m has been applied to income-generating projects to date, and it is likely to be some years before the full proceeds are invested in projects, if ever.

“We can do so much more with the wealth at our disposal.”

What is preventing this money from being put to use? Institutional conservatism probably plays a part. This is a five-hundred-year-old institution. Some bursars claim to be circumscribed by tradition, with ‘funds [... ] reserved for specified purposes, such as funding fellowships or student support, with conditions set by donors centuries beforehand’. The ongoing marketisation of education, as well as the conditions of capitalism, stifles any attempts to suggest that we do not need this much money or land.

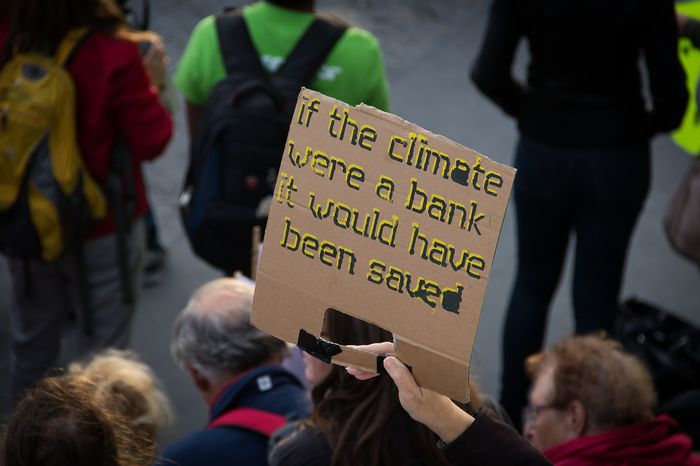

Imagine what this money could be doing. Imagine if it was used to fund the radical climate action we mentioned earlier; to help the University make amends for what Quigley et al.’s 2019 divestment report calls its ‘disproportionate historical and current emissions’, to set ambitious and achievable net-zero deadlines of 2030 or earlier, as numerous other Russell-Group universities have done, from Glasgow, to Nottingham, to Leeds. Setting these targets is our responsibility as a privileged institution in the Global North, which for so long has profited from the exploitation of the communities who are already paying the price for the climate crisis we caused, like last years’ Jesus College Climate Justice Campaign report notes.

“[The University’s] wealth-hoarding is ideological.”

But we can do so much more with the wealth at our disposal. Colleges’ persistent refusal to pay the living wage, as well as their insistence on unnecessary redundancies, is the focus of the Justice for Workers campaign, which will continue to campaign for just pay and fair working conditions in the year to come. University and college management have no excuse not to pay all employees the Real Living Wage. We can’t emphasise this enough: the University of Cambridge is the richest higher education institution in the UK. Its pockets are not tight, and its wealth-hoarding is ideological.

So what can we do? Joining the Justice for Workers campaign in your college, or starting one, is a fantastic start to getting the University to start living up to its responsibilities as an employer and an educator. The conversation around the University’s landholdings has only just begun, so do get in touch if this is something that interests you. We’ll need to map the problem before we can take action, but already you can see the possibilities, can’t you? A university that gives back to the community, which commits to stop buying up land in Cambridge and starts working with the local people to make more of its existing land accessible to the public, and where possible, sells its assets back to the community.

It’s not a pipe dream, which only sounds radical because the University has been allowed to keep up the appearance that its proverbial pockets are empty, even though it has billions in the proverbial bank. As much as they’ll try to deny it, our assets can create positive social change — there are endless opportunities for this — we just have to learn to let go of them.

Another idea: the University’s swathes of capital could be put to use funding the ‘research’ mentioned in its mission statement, research which could genuinely ‘contribute to society’, because right now our research funding, and consequently the direction of this research, is in considerably more dangerous hands — something we will explore in the final part of this series.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025