Cambridge Spotlight: New fossil reconstructs the origins of starfish

In this installment of Cambridge Spotlight, Izavel Lee explains how research on a starfish-like fossil has shined a light on their evolutionary history

Starfish may seem like simple creatures, but tracing their evolutionary history is no simple task at all. As members of a larger group of animals known as the echinoderms, starfish and their relatives – including sea cucumbers and sand dollars – have seen extraordinary success over the eons, with thousands of living species catalogued so far. Thousands more have long since gone extinct, forming part of an extensive fossil record. Unfortunately, this diversity has also made it difficult for scientists to figure out how echinoderms all relate to each other.

Now, a newly reported echinoderm fossil may help to untangle these relationships. In an article published last Wednesday in Biology Letters, Dr Aaron Hunter and Dr Javier Ortega-Hernández have described an extinct echinoderm – Cantabrigiaster fezouataensis, the oldest known proto-starfish and a key intermediate in the evolution of starfish. Hunter is a visiting researcher at the Department of Earth Sciences and Ortega-Hernández, previously from the Department of Zoology, is currently at Harvard University. The genus name is a homage to the cities of Cambridge in the UK and USA, where a number of important echinoderm researchers have worked.

"However, there still remains other mysteries surrounding the origins of starfish, such as why they’ve evolved five arms."

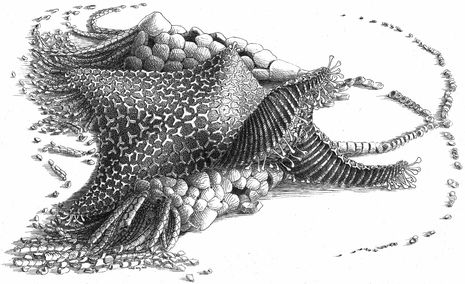

Cantabrigiaster is one of numerous fossils to have come out from the Fezouata Shale in the Anti-Atlas region of Morocco. Conditions in the Fezouata formations have allowed even soft tissues to be preserved, a rarity amongst fossils. Species in this deposit date to the Early Ordovician over 480 million years ago, a period of time when there was an explosion in the biodiversity on Earth. Echinoderms like Cantabrigiaster tend to be particularly well-preserved as fossils due to their calcite skeletons, a mineral made of calcium carbonate. This is the same mineral that goes into limestone and marble.

The group of echinoderms that the pair’s research focused on is known as Asterozoa, which includes starfish and their close relatives, like the brittle stars and basket stars. The new fossil is part of an extinct sub-group known as the somasteroids that existed before the other asterozoans. However, Cantabrigiaster is unique among the somasteroids because its arms lack a particular series of ossicles, or calcite plates, that is present in more modern species of asterozoans. This trait makes it similar to an entirely different group of echinoderms – the crinoids, better known as sea lilies.

In fact, this similarity between Cantabrigiaster and sea lilies is what first inspired Hunter to realise that this fossil was no ordinary somasteroid. “I was looking at a modern crinoid in one of the collections at the Western Australian Museum and I realised the arms looked really familiar, they reminded me of this unusual fossil that I had found years earlier in Morocco but had found difficult to work with,” he said in a press release.

To come to this conclusion, the researchers performed a phylogenetic analysis, where they compared anatomical traits across 38 echinoderm species. The basic principle behind this analysis is that the more anatomical features two species share, the more closely related they are. To be precise, species with more similarities share a more recent common ancestor than those with less similarities. For example, while the common ancestor of humans and dogs existed nearly 100 million years ago, our common ancestor with chimpanzees existed about 6 million years ago.

When selecting traits for comparison, Hunter and Ortega-Hernández applied a model known as extraxial-axial theory. By looking at how echinoderms develop from an embryo to an adult, they could make sure that they only compared anatomical traits that developed in the same way during the lifetime of an echinoderm.

The results showed that Cantabrigiaster forms the most ancestral lineage of asterozoans, and the starting point for the evolution of more modern species we see today. By comparing the form of Cantabrigiaster with later species, the team was able to infer key steps in the evolution of starfish. Their research also produced new ideas about the relationships between different asterozoans.

However, there still remains other mysteries surrounding the origins of starfish, such as why they’ve evolved five arms. “It seems to be a stable shape for them to adopt – but we don’t yet know why,” said Hunter. “We still need to keep searching for the fossil that gives us that particular connection, but by going right back to the early ancestors like Cantabrigiaster we are getting closer to that answer.”

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026

News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026