A Brief Guide To Building Better Cities

“Cities are defined not by their skylines,” argues Grace Blackshaw, regarding the future of urban life, “but by the people that live and work within them.”

Type the word “city” into Google Images and you’ll see a page full of skyscrapers. Indeed, global cities are often defined by their most famous skylines. However, more than half of the world’s population live in urban areas and for many these towering glass facades are a far cry from their daily reality.

The 11th UN Sustainable Development Goal is to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable by the year 2030. Suffice to say, there is a lot of work to be done. Nearly one billion people live in informal settlements, sometimes without access to basic services, including water and electricity. Despite only taking up 3% of land, cities are responsible for 75% of global carbon emissions and 70% of energy consumption.

This article presents a whistle-stop tour of some of the latest technological developments and policy guidance that might help cities of the future be better than those of today.

When it comes to the climate crisis, a 2019 report from the Coalition for Urban Transitions argued that “the battle for our planet will be won or lost in cities”.

“Surpassed only by water, concrete is the second most widely used substance on Earth”

To reduce emissions, cities will need to electrify transport, heating and cooking, and increase local renewable energy generation. In addition to rooftop solar panels, companies such as SolarWindow Technologies are developing the technology to turn windows into solar panels by simply applying a thin transparent coating.

Cities will also need to be more efficient with the energy they do have. As the tallest building to achieve Passivhaus standards, the Bolueta Building in Bilbao pushes energy efficient design to new heights. Measures such as triple glazing and airtight seals mean the building uses 75% less energy than the average new construction.

Another approach is to rethink the materials we use. Surpassed only by water, concrete is the second most widely used substance on Earth, and it comes with dire environmental impacts. Concrete is responsible for 8% of the world’s carbon emissions and almost 10% of industrial water use.

One approach looks at developing low-carbon cement and concrete. Others argue that we are too quick to demolish and replace buildings, and that we should instead focus on adapting existing buildings and reducing materials. Designed by Lendager Group, Upcycle Studios uses recycled concrete, reclaimed oak floors and windows made from two reclaimed double glazed panels.

“Globally, more than 90% of urban dwellers are breathing unsafe air”

A far cry from holiday log cabins, others suggest that engineered timber could play an important role in the future of tall buildings. Last year, Cambridge’s own Centre for Natural Material Innovation exhibited their proposals for wooden skyscrapers. As Principal Investigator Dr Michael Ramage explains, “The sustainable forests of Europe take just 7 seconds to grow the volume of timber required for a 3-bedroom apartment, and 4 hours to grow a 300-metre supertall skyscraper.”

The environmental impacts of cities extend far beyond their construction. For decades, roads have been built for cars, rather than people. In addition to environmental impacts, the prevalence of polluting road traffic has severe impacts on public health. Globally, more than 90% of urban dwellers are breathing unsafe air, resulting in more than 4 million deaths each year. The Centre for Cities’ recent report shows one pollutant, PM2.5, alone caused more than 14,400 deaths in UK cities in 2017.

All around the world, scientists and policy makers are working on projects to reduce air pollution in cities. Closer to home, one group of Cambridge researchers have developed a graphene composite that degrades common atmospheric pollutants and could be used as a coating on pavements and buildings. Another group of researchers is working on low-cost air quality sensors to monitor air pollution in London.

Based on data from similar sensors, Siemens has developed software that displays real-time information on air quality and uses an artificial neural network to predict values for the next five days. Projects such as this highlight the potential of smart cities, which use information and communication technologies to improve a city’s efficiency, liveability and sustainability.

“Large cities have been shown to be more unequal than the nations that host them”

In May, as the coronavirus lockdown was being eased, Sadiq Khan announced that areas of London would be closed to cars and vans to allow people to walk and cycle safely. While the plans are currently only temporary and primarily designed to limit the number of people using public transport, similar measures could play a key role in any “green recovery”.

However, while pedestrianised streets, cycle paths and more green spaces seem like a no-brainer, the authors of this Nature article argue that such localised policy change often overlooks their broader socio-economic impacts. In a process they term “environmental gentrification”, as districts become greener, their desirability increases, and it becomes increasingly expensive to live in them. This results in social displacement, as lower income residents are often forced to move away to more suburban neighbourhoods, with longer commutes and without any of the benefits of original “greening” efforts.

Given that large cities have been shown to be more unequal than the nations that host them, this is indicative of some of the broader socio-economic challenges that desperately need addressing. What’s the point of building ever more impressive skyscrapers, with the latest sustainability specs and rooftop gardens, if they are inaccessible to the majority of the population? What’s the point of more green spaces and improved biodiversity, if it only worsens social inequality?

For the nearly 1 billion people currently living in informal settlements or “slums”, their lived reality is even further removed from the shiny glass skyscrapers this article opened with. It is difficult to make generalised statements about the nature of informal settlements as they differ dramatically. However, they are characterised by overcrowding, poverty, unsafe or unstable housing and a lack of basic services.

Historically, slum clearance has been implemented as an urban renewal policy. However, forcible eviction is increasingly condemned as unjust and ineffectual. The eviction of over 700,000 people from slums in Zimbabwe in 2005 has since been labelled ”a crime against humanity" by independent legal experts. Instead, Kim Dovey, Professor of Architecture at the University of Melbourne, argues that in almost all cases, informal settlements should be upgraded in situ.

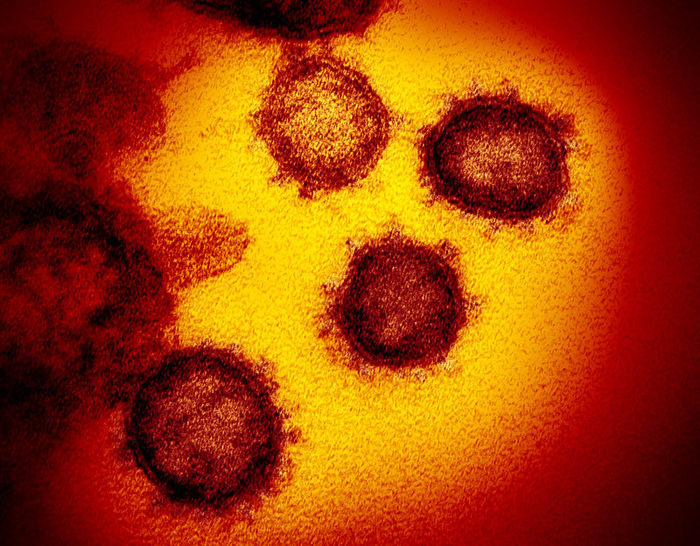

Poverty and informal housing also make communities more susceptible to external threats such as rising sea levels as a result of the climate crisis and public health crises such as the coronavirus pandemic. As much as 50-80% of employment in developing cities is informal, meaning families often survive hand to mouth. Hence, for millions across the world, lockdown measures such as “working from home” and “self-isolation” have proven impossible.

When discussing informal settlements, it can be tempting to paint urban poverty as a concern primarily confined to the developing world. However, as I write this article on the third anniversary of the Grenfell Tower fire, I am acutely aware that race, class and poverty can have just as profound an impact on an individual’s experience of urban spaces in the UK as anywhere else.

Cities are defined not by their skylines, but by the people that live and work within them. If politicians, town planners, architects, engineers and other stakeholders genuinely aim to make cities more inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable, this needs to be remembered.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026