My first patient, a human cadaver

Shazia Absar shares her experience of learning human anatomy in the dissection room

Perched on the wooden benches of the anatomy lecture theatre, we were told to reflect on how we might feel when we see a preserved cadaver for the first time, as we would very soon. We were warned that some people feel nauseous, others feel anxious, while some may feel an overwhelming sadness at the thought of the cadaver in front of them having once had a life, a family and people who loved them. I was certain I would be one of the students who fainted at the mere smell of the preserved bodies and I was hit with the tragic realisation that the first memory that my classmates would have of me would be me crashing to the ground.

Oddly, yet thankfully, this was not the case.

Entering the dissection room for the first time was an almost surreal experience for me. It baffled me that I was currently surrounded by at least 40 cadavers, yet it seemed so normal. Even looking at our donor’s face for the first time did not feel disgusting or harrowing at all; rather the donor almost looked fake, like wax or plastic, but certainly not someone who had once been alive.

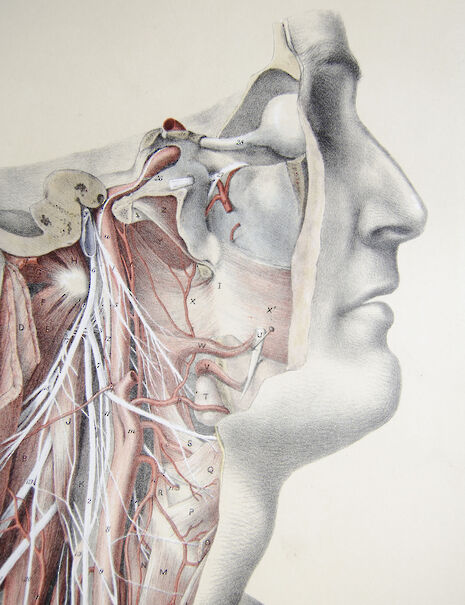

Over the course of the year, our donor became both more and less life-like to me. In one sense, as we dissected and examined every part of his body, our donor felt less and less like a man who had once lived and more like almost a mannequin made for our education. But, in another more pertinent sense, our donor was brought to life. We would see a scar on his leg and wonder how it got there. Did he fall? Had he cut it by accident? Examining his abdomen we found he had a specific embryological abnormality and wondered: did he ever know this?

Throughout the year, we saw things about our donor that many would never have known, including our donor himself, and this, for me at least, felt like a great privilege.

To know that someone, so selflessly, would give their body to a bunch of first year medical students so that they could learn anatomy, is something I still find baffling. To care so much about the education of people you do not and will never know that you would choose to leave your body in their hands is something I could never understand, but something for which I am eternally grateful.

People say your donors are your “first patients” and I agree. Every other patient I see in my career will be a variation of the donor I dissected back in my first year of medicine. Every heart will be bigger or smaller than the donor’s, every liver will be harder or softer and every anatomical fact I remember will be guided by what I saw during dissection sessions.

In a subject which is often plagued by the idea of having to memorise endless insertions and innervations of even more endless muscles, dissection was a constant reminder that what we learn as first year medical students will be important for the rest of our careers. It was an experience that displayed that, despite the looming deadlines and countless essays I was supposed to write that weekend, the course I was doing was an essential and rewarding one, where the lives of real people would one day be in our hands.

Dissection of a human cadaver is a privilege that only a few are able to experience. At undergraduate level, it is essentially limited to only medical students, and more so, only those studying at certain institutions. Reflecting on my experiences a year later, I have truly come to understand and appreciate the value and importance of the experience that we had twice a week for a year, knowing that I won’t forget the lessons I learnt during this time (even if I have already forgotten all the facts).

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026