New year, new me? Not if you don’t really want to change

With two thirds of British adults failing to keep their New Year resolutions for more than a month, Raphael Korber-Hoffman spoke to behavioural psychologist Dr James Erskine to find out why

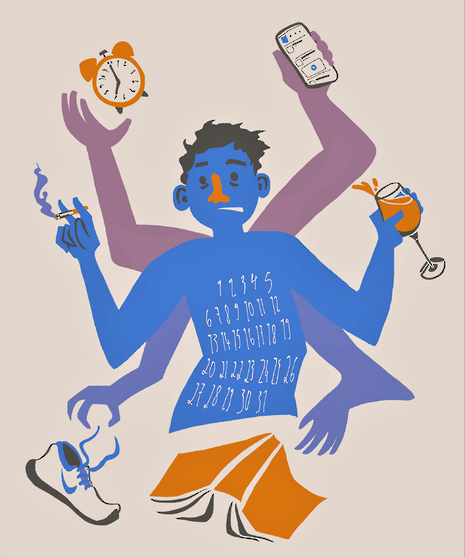

January can be a difficult month, with the new year’s festivities soon giving way to a gloomy return to work. There are short days, long nights, and the weather only gets colder. For many, January brings with it an extra strain in the form of attempts at New Year resolutions, often focused on weight loss, quitting smoking or other forms of self-improvement. Searches for gyms on Google spike by up to 40% in January in some cases, with gyms recruiting as many optimistic would-be fitness gurus as possible each new year. At Planet Gym, 50% of their members don’t even make a single visit. Why are people statistically so unlikely to follow through on their own goals, even when the benefits are so clear, and the costs, with habits such as smoking, so dear? This was the question that a sold-out audience at the Blue Moon Pub had come to find out from a man who has spent decades researching this question.

“This time of year, it’s a little artificial”, Erskine tells me over a beer in the pub where he is about to give his talk at an event run by the Cambridge Skeptics. “Because it’s the right time of year, people decide unilaterally that they are going to change, and it’s not a great way of doing it because you have to be ready for the change.” I ask what being ‘ready’ would entail, and he responds that it is when “your back is against the wall, you have to change now. If you’re not sure or you’re ambivalent, it’s just not going to work.” What Dr Erskine’s research boils down to, essentially, is that people only change their behaviour when they have a strong enough desire to keep going despite the challenges. A helpful factor would be a conscientious personality without a high degree of neuroticism, but Erskine believes that more important is having a support network. “If you haven’t got support … you’ll frequently fail.”

“Failure is a theme which runs through our interview, with Erskine decrying the emphasis placed on it”

Part of the reason why so few resolutions make it out of January is due to what Erskine calls the ‘what the hell effect’. “Where I think resolutions and intentions fall down”, he elaborates, “is on you being overly hard on yourself when you fail. The classic is not that you don’t succeed. You succeed for a time, and then you fail. At that point you have a choice, you can re-instigate it, or you can say ‘what the hell’ and go off the rails. The classic is you go off the rails.” The key to not falling at the first slip up, Erskine says, is not to worry too much about the failure. It’s important that if “you have one cigarette on 15th January [don’t] view that as cataclysmic. Say, ‘ok, I had one cigarette, not such a massive deal… I’m still a non-smoker.’” Deciding to give up is just making the failure permanent.

Failure is a theme which runs through our interview, with Erskine decrying the emphasis placed on it, especially by Cambridge students. Somewhat gloomily, Erskine makes the point that freshers arriving each September are “setting themselves up to fail because you come to a place which is so selective in its criteria for entry that you’re among the best of the best. Anything less than great, you’re found wanting.” So does Cambridge produce as much low self-esteem as it does good grades? It all depends on outlook, as Erskine points out: “The way around that is not to mind failing, basically . . . failure is never failure, it’s a stepping stone to getting the right answer. And I think that mindset really helps to put yourself out there.” Such an attitude, he adds, would also solve the main problem of many a late-night essay writer. “Procrastination is often seen as a way of avoiding future judgement . . . I think that one of the tragedies is that people view failure as detrimental.” Further, Erskine urges students to be realistic with themselves and not set too high a bar – “Why make life hard? It’s hard enough already” – and come to terms with striving to be the best they can, but not more. But with a willingness to fail being massively beneficial, as Erskine argues, I ask why so few people seem to have this trait. The numbers seem to be going down, Erskine responds, partly due to social media.

Cambridge provides many opportunities for that idyllic Instagram shot over the Cam, or that classic millennial snap of avo toast, but Erskine sees no sign that this is making any of us happier, or more resilient against let-downs or criticism. “It sells a lie that everyone can win, and it’s just not the way the world works. So if you are chasing financial status, amazing experiences, nights in fantastic restaurants, then not everyone can and that’s the simple fact . . . but we’re constantly bombarding ourselves with people who are above average, and find ourselves wanting.” If there’s little contentment to be found in the supervision room or online, I ask Dr Erskine how people can find happiness. Unfortunately, the psychologist has more bad news. “You can never be consistently, chronically happy”, he says, but this is a good thing as if it were the case “it would be a calamity… imagine being in love, you’d not notice a car when you cross the road.” Rather, we should aim for general contentment in our lives, “what makes a huge difference in future happiness is having more time off . . . beyond £40,000, earning more doesn’t make us happier. If you want a contented life, buy experiences not things. And then focus on relationships with people that mean something to your life. That will be a contented life.”

After an hour of discussion, Dr Erskine excuses himself to head outside for a smoke. I follow him out to leave through a cloud of cigarette fumes drifting off into the crisp January air.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 News / News in Brief: carols, card games, and canine calamities28 December 2025

News / News in Brief: carols, card games, and canine calamities28 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025