Progress, one woman at a time

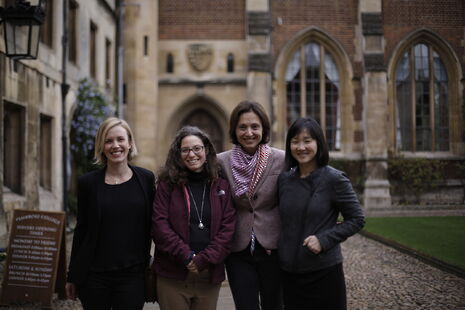

Women scientists are doing pioneering research across Cambridge. Rachael Barrett speaks to four of them about their work

Dr Maria Ubiali stumbled upon her love of physics while babysitting a scientist’s child, who told her that “the physicist is an artist who can’t draw”. Laughing, she reaffirms that she doesn’t regret the choice at all. Studying theoretical physics in Milan, she was advised to go abroad to further her career, finally moving to Cambridge where she was recently awarded a lectureship. Her work involves “asking fundamental questions about the building blocks of matter” by investigating the structure of protons.The first scientist in her family, Ubiali owes her encouragement to two men, her supervisors, but admits that there were times in her life – particularly after career breaks when the environment coming back seemed “hostile” – when she felt she needed to talk to a woman. “Since then,” she explains, “I took it as a sort of mission to talk to younger women myself because I think many people don’t have the encouragement that I had”.

She has watched many talented women fall victim to the leaky pipeline who “honestly would’ve been amazing professors at any university” – offering the lack of encouragement post-career break and childcare as explanations. Ubiali explains: “When I go to a conference [my daughters] feel very excited; they don’t know anything about it, but they feel proud.” Through them she tries to understand why fewer girls go into physics, suggesting discouragement from teachers as a factor. Ubiali urges women not to be intimidated. “You often meet people who are very sure of themselves; I think you’ve got to be confident and keep asking until you get an answer that you understand...you should be humble but persistent and passionate.”

"Today, she wants to reassure her students that “you win these things because you deserve it"

“My career path is not what is thought of as the classic science career path. It didn’t work out that way for me.” Dr Lovorka Stojic followed her science away from post-war Croatia to Zurich, Naples, and finally to Cambridge. Publishing 18 papers in top journals including Nature Communications and Science, she now hopes to establish her own lab in the Department of Biochemistry as early as April 2019. Stojic works on non-coding RNA; she tries to understand their role in important cellular processes like cell division, and through this their importance in cancer. Alongside this she is a mother of two, but rather than having the diminishing effect on her career, motherhood heightened her pangs for the lab: “Officially I was off but mentally I wanted to be in, I wanted to be involved” – resulting in anecdotes of breastfeeding while analysing data with her masters student. The determination required for such a balancing act shouldn’t be underestimated. Best put by Stojic’s old boss at Harvard after having his own child, “How did you get this done?”.

In reply she avoids self-congratulation, explaining that it was necessary for the completion of her project, instead choosing to emphasise the wonderful support network of family, friends and colleagues who have helped her throughout, in particular naming Professor Adele Murrell (University of Bath) and Dr Fanni Gergely (Cancer Research UK) as people who believed in her throughout her time at Cambridge. Recalling Saturday coffee mornings with Adele where the two would discuss science, she adds “I will never forget that, and I am grateful to Adele for her support”. Stojic wouldn’t say she was treated differently as a woman in science, emphasising that regardless of gender “you have to have a hard skin, because it’s not going to be an easy path”. She says that the most important thing is to be passionate, because “at the end of the day it starts from you, and you should not be intimidated at all”.

"I think you’ve got to be confident and keep asking until you get an answer that you understand...you should be humble but persistent and passionate."

“Let’s try physics and see what happens.” Dr Diana Fusco describes her career as a “random walk around the different fields of science”. Trained as a theoretical physicist in Milan, she went on to do a PhD in computational biology and finally, tired of computational work, said, “That’s it, I’m going to learn how to do experiments”, falling in love with molecular biology and the “magic that can be done with it”. New to lecturing in Cambridge, with a child on the way and presently setting up her own lab, she continues her postdoctoral work on how bacteriophages evolve and adapt to a bacterial lawn spread in 3D space and how interactions with each other have consequences in their evolution. When asked if she’s a converted biologist now, she says that “I like to think so, but I still do think how I pose a problem is from a physics perspective”.

Physics is notorious for being a male-dominated space; Fusco, however, observes that “once you’re there, there is nothing that makes you feel different because you’re a woman”. However, she recounts unpleasant experiences working with female role models, who “belong to another generation of women for whom the gender bias was greater; for them to make it to a particular career point they had to be really harsh and strong”. After this she feels both “honoured and responsible” when acting as a mentor for students, especially girls.

“I took it as a sort of mission to talk to younger women myself because I think many people don’t have the encouragement that I had”

Though she reports no unpleasant gender-based experiences in the lab, she mentions both male and female colleagues playing down her accomplishments, saying “of course you won, you’re the only woman taking part in it” – an attitude that affected her at the beginning of her career. Today, she wants to reassure her students that “you win these things because you deserve it”. Fusco remains positive that the gender gap is narrowing, citing the first female Nobel laureate in Physics in 55 years as a mark of progress and a role model for girls, so long as nobody is crediting that victory to the fact she’s the ‘token woman’.

Women are two and a half times less likely to ask questions in seminars, study finds

Dr Jenny Zhang’s research crosses boundaries between the sciences, “Chemistry is the glue holding all the different sciences together – everything involves atoms and molecules”. Getting her own fellowship let Zhang diverge from her anti-cancer drug roots into different fields, something she described as “liberating”. She combines her PhD and postdoctoral work researching the bioenergetics and redox chemistry of photosynthesising cyanobacteria, harnessing a phenomenon where bacteria secrete electrons, effectively acting as a power cell. Zhang points out the more “insidious” forms of discrimination “that are in the undercurrents and less obvious but because of this is more pervasive", giving examples like the allocation of female scientists to administrative roles and constant interruption by men when talking at important meetings. All of Zhang’s principal investigators have been male; she acknowledges that “without their support it wouldn’t have been possible”, explaining that it pushed her to become a PI herself.

She thinks that community among women scientists is important, saying that “it’s really nice to be able to validate each other’s struggles”. Referencing the allocation of women to clerical roles, Zhang makes the important point that, probably because of culture, women are usually very agreeable when asked to work behind the scenes to further the progress of the team. However, she warns female scientists not to over-volunteer, advising them to “do more things that scare you. It's fine to be scared, but do it anyway. Only then are you being truly courageous". Naming two-time Nobel Prize winner Marie Curie as one of her role models, Zhang thinks the two female Nobel laureates this year are marks of “excellent progress” but remains cautious: “It’s important to know also that while we’re making progress, there’s still a long way to go.”

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026