The future of biological publishing is open

Bethan Clark examines ‘preprints’, which have revolutionised publishing in biology this year

At the end of every year, the news fills with round-ups and rankings of the events of the past 12 months. Science is no exception – and this year, there’s an unusual contender in the mix. It is, in fact, not a scientific discovery, but a movement changing the way the discoveries themselves are communicated, with far-reaching implications for the future of the scientific process.

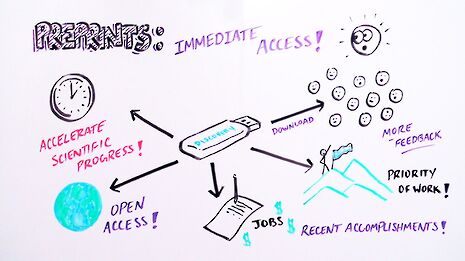

The change is based on publishing papers early, as so-called preprints: unreviewed versions of scientific papers posted online, before the papers are published in a peer-reviewed journal. Though innocuous, and perhaps a little dry at first glance, this practice is fuelling the start of a biological revolution. Early in the year, UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, the NIH and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute all endorsed citing preprints in grant proposals, while in April, the biggest platform that hosts preprint archives received major funding input from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

But where do preprints come from? They aren’t actually new themselves; it is their use in biology that is. Physicists have been posting them online since 1991, when the non-profit preprint server arXiv was set up. Even decades earlier than that, high-energy physics had a preprint culture with labs posting each other copies of papers as they were submitted to journals. A short-lived project in the 1960s attempted something similar in biology, with the NIH mailing draft manuscripts to groups of biologists, but otherwise the life sciences missed out on the birth of the preprint practice.

“Preprints have undoubtedly made their mark on the research landscape of 2017”

Then came the 21st century, and with it, specialist servers. In 2003, arXiv launched a quantitative biology section. Preprints started to trickle in and were soon being posted at a steady – if low – rate. The key, however, was the opening of bioRxiv (“bio-archive”) by Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory in 2013. Since its launch, bioRxiv has attracted a rapidly increasing number of preprints and now holds more than 15,000 papers. It’s not alone: multiple other platforms have followed since, even if bioRxiv remains dominant.

Unlike the quiet take-up of preprints in physics, in biology the move has been accompanied by much fanfare and controversy. Critics question whether the quality of research will be at risk without the stringent peer review process of traditional journals. Equally, there is the concern from researchers that posting preprints of their work might put them in danger of having a breakthrough scooped, by spurring competitors to publish earlier. So far, most of these fears have not proven too justified. Preprints aren’t actually replacing peer-reviewed publishing, rather complementing it. After all, most papers posted as preprints are usually still sent to journals afterwards. The key is simply that they are available to other researchers much earlier, as the publishing process is often protracted.

Here, then, is where the true potential of preprints arises: results can be shared with colleagues much more quickly, generating healthy competition as well as catalysing collaboration and integration of knowledge. In essence, preprints have the power to turbo-charge scientific results. They also alter the relationship of biologists with journals, given that these are no longer the only way to communicate findings within the scientific community. That said, Nature and Science should not yet worry: the value of journals is safe, as they are still seen as the ultimate judges of a paper’s scientific integrity. What preprints do here is give researchers more flexibility in navigating the often-harsh system.

With the trend set to continue, there are a wealth of opportunities as well as lingering concerns for preprints in the biological sciences. After so much speculation, the full extent of their impact remains to be seen. However, they have undoubtedly made their mark on the research landscape of 2017

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026