Event: CUCO performs The Epic of Everest

Imogen Sebba is impressed by this epic performance

The word ‘epic’ is overused these days. A skateboarder falling over is hardly an ‘epic fail’. A large amount of bacon doesn’t constitute an ‘epic meal’. But a quest for survival, to succeed in conquering a force of nature in a way that mankind had never achieved before, featuring first-hand footage from 1924 and an emotive, powerful score executed brilliantly by CUCO and guest conductor Andrew Gourlay, truly was an epic tale.

The British Film Institute has restored this silent film from nitrate positives, charting the third attempt to reach the summit of Everest, costing the lives of mountaineers George Mallory and Sandy Irvine. The original soundtrack – part written by the best of London’s musical talent of the 1920s, part borrowed from Romantic symphonic works with exotic themes – has been living in the University Library.

There doesn’t seem a better way to exhibit it, or indeed a better time: CUCO proved last month how well they cope with Mozart, Beethoven and classical music’s ‘greatest hits’: how marvellous to see them do even better with something completely different.

It’s remarkable how CUCO manage to achieve such unshakeable ensemble: Gourlay was bound inextricably to the film, unable to make any allowances in timing for either practical or musical reasons. There may have been a small passage of repeated notes where perhaps the horns felt shakey, but in such fragmented and technically difficult music, it felt for the most part remarkably fluid and relaxed.

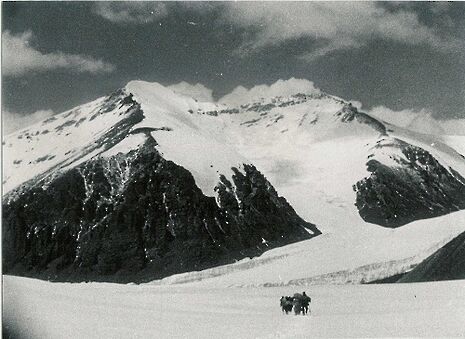

Solos from violin, cello and flute soared above the orchestra, and special mention must go to Will Ball’s cor anglais solo at the opening of the film, as the text plates begin to appear alongside imposing shots of Mount Everest. Many were still unsure of what to expect, and a fairly ambiguous melody without accompaniment usually wouldn’t have helped the matter, but it had great direction without detracting from the film’s opening.

The evening felt more of an immersive experience than a conventional concert, and no more so than when, at the climax of an extract from Mussorgsky’s dramatic 'Night on Bare Mountain’, the footage paused and Gourlay turned to address the still-gripped audience. Certainly individual moments stand out more in the film than in the highly atmospheric score – the birth of the donkey or the laughing Tibetan woman were favourites amongst the audience – and it’s a shame that, in the most riveting scenes, at the climactic point of the film and of the world, that the score takes just a few seconds too long to respond to the announcement of the mountaineers' deaths.

Overall, however, these small complaints can’t detract from an evening that provided wonderment and drama in equal measure, capturing the soul with a desire for adventure, with music that could break your heart.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025