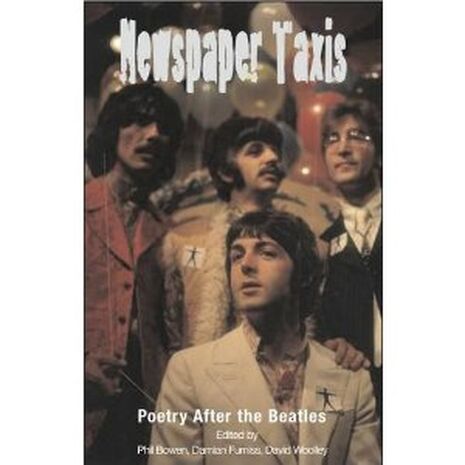

Books: Newspaper Taxis: Poetry after the Beatles

William Kennaway discusses the newest anthology of Beatles inspired work

As 2013 marks the fiftieth anniversary of ‘Beatlemania’, the year will see a huge array of commemorative merchandise produced. Perhaps the most interesting result of this celebration, though, is a new anthology of poetic responses to the Beatles and their songs, entitled Newspaper Taxis: Poetry After the Beatles.

Featuring work from Simon Armitage, Carol Ann Duffy and Philip Larkin, the collection is interesting besides its novelty value, as the poems are chosen with a discriminating deftness. A particular highlight was Katherine Stansfield’s ‘Relic’, a witty response to the sale of one of John Lennon’s teeth at auction for thousands of pounds with compelling things to say about the way we use the past.

Another especially good poem is Armitage’s ‘The Sad Panda’, a delightfully weird kaleidoscope of a dramatic monologue from the point of view of, as you might infer, a sad panda. So, yes, it’s a good collection. There’s still probably a broader question to be answered though: is there any particular impetus to create commemorative editions like this outside of the obvious financial ones?

The intention is probably that, with 50 years having passed since the rise of the Beatles, we can look back on their works with a new kind of objectivity. Perhaps putting these particular poems together creates a whole a new way of looking at the Beatles and their cultural impact. While it is surprising just how many varied poetic responses to the Beatles there have been over the past 50 years, it still feels a little contrived.

As mentioned, Carol Ann Duffy is featured here, writing commemorative poetry of a different sort as our poet laureate. There is a feeling that the works produced by poet laureates are generally rather contrived and a little kitsch. Duffy’s poem commemorating the Olympics, for instance, is enjoyable enough, but hardly that’s going to win any Nobel prizes for literature.

Maybe that fear of institutionalised, contrived verse is why Wordsworth was so hesitant to take up the position in 1843. He finally agreed only on the condition that he was never required to write any poetry, becoming the only poet laureate ever to write no official poetry.

Wider issues about the role of commemorative poetry aside, this is still a pleasant collection, with enough quality to be of just as much interest to poetry fans as to fans of the Beatles

Comment / Good riddance to exam rankings20 June 2025

Comment / Good riddance to exam rankings20 June 2025 Features / Cold-water cult: the year-round swimmers of Cambridge21 June 2025

Features / Cold-water cult: the year-round swimmers of Cambridge21 June 2025 News / State school admissions fall for second year in a row19 June 2025

News / State school admissions fall for second year in a row19 June 2025 Lifestyle / What’s worth doing in Cambridge? 19 June 2025

Lifestyle / What’s worth doing in Cambridge? 19 June 2025 News / Pro-Palestine protesters occupy Magdalene with encampment flotilla21 June 2025

News / Pro-Palestine protesters occupy Magdalene with encampment flotilla21 June 2025