Not on our turf: Shamima Begum and the British Imperial ‘Self’

Lily Maguire believes that Britain’s treatment of Shamima Begum is rooted in an enduring conception of its Imperial ‘Self’.

On the 26th of February, the Supreme Court ruled that Shamima Begum – a British-born woman who left the UK for Syria to join the Islamic State – couldn’t return to contest the revoking of her British citizenship in 2019. Denied citizenship by the government of Bangladesh, Begum has been left stateless in a dangerously defiant suspension of Article 15 of the Declaration of Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to a nationality”.

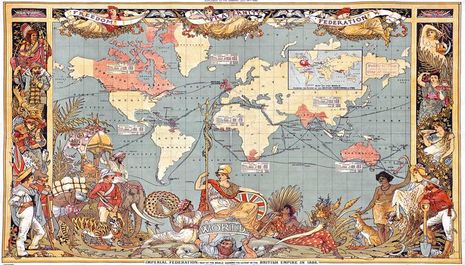

The ruling reflects a pervasive historical tradition where the UK has sought to symbolically conceal innate contradictions within British Imperialism. “Britishness” was built upon a paradox between claims of civilised superiority and practices of imperial atrocities. Yet to distract from Britain’s internal hypocrisies, an image was constructed of an external world demarcated between the civilised West and the uncivilised ‘Other’, identifying barbarism as existing exclusively outside the UK.

“Stripping away her citizenship denies Britain is the problem.”

This is re-emphasized whenever the British ‘Self’ is threatened by decline, blurring public visibility of the barbarism of Britain. In 2021, the halo surrounding Britishness has dissipated in national imaginaries following years of crippling austerity and right-wing nationalism culminating in the internationally mocked Brexit vote. With the UK being the fifth worst affected country by COVID-19 globally, the illusion of British exceptionalism is revealed, sparking a need to define an ‘Other’ to solidify identity again. Shamima Begum has been used for this cause, reduced to a stateless “object in the midst of other objects” of which Fanon speaks. Despite Begum being born, bred, and radicalized on British turf, stripping away her citizenship denies Britain is the problem, exorcising the legacies of imperialism and claiming inhumanity belongs only to the external world.

Early imperial encounters between Western and non-Western nations destabilized the British ‘Self’ through creating opposing consciousnesses: British moral purity posited against the conscious barbarism of its Empire. Colonisers watched as genocidal violence and the devastating destructions of ecosystems for resource extraction unfolded, all for the pursuit of British hegemony abroad and ‘liberal’ prosperity at home. The paradox of liberalism in the domestic sphere requiring illiberalism internationally meant colonies were mirrors, reflecting the barbaric potential of Britishness back at Britons. Empire provided places where moral standards were suspended, and violent fantasies enacted. Western culture was posited as self-improving by separating out the good from the bad, but in reality, Britain denied its innate darkness through displacing blame onto outsiders.

“When the two-faced duplicity of Britishness is exposed, disillusionment oscillates through society.”

Centuries later during the War on Terror, popular discourse demarcated the globe between Western “cultures in which First Ladies give speeches” and others where women “shuffle around silently in burqas” as explored by Lila Abu-Lughod. Binary rhetoric of the civilized UK fighting savage terrorists to save damsels in distress concealed the real conflict: between the UK’s claims to be giving Muslim women their voice back and the blatant suppression of those crying that war would ruin Afghan and Iraqi women. Shifting from vivid descriptions of helpless Muslim women to justify war under the guise of human rights, to painting Begum as a rights-less weapon, exposes the artificiality of politicians professing she poses a “national security” threat.

When the two-faced duplicity of Britishness is exposed, disillusionment oscillates through society, threatening the British ‘Self’ with implosion. During such times, objects of hatred are needed more than ever, inaugurating the strengthening of a non-British ‘Other’ rather than interrogating the UK’s internal failures.

The 21st century has ushered in devitalizing damage to the myth of British exceptionalism. Globalization triggered unprecedented levels of competition between the British state and supra-national organizations rendering many unemployed as jobs were offshored to the Global South. The 2008 financial crisis triggered paralysing policies of austerity and radical rises in income inequality leaving the British ‘Self’ in severe crisis, offloading responsibility onto the ‘Other’ as seen in the way that the Brexit campaign targeted Eastern European immigrants. During the pandemic as the government has failed to control COVID-19, Susan Williams, the Home Office minister for countering extremism, reported a 21% rise in anti-Asian hate crimes.

Shamima Begum has been used to solidify national identity in this way. The removal of her citizenship denies Britain is the root of the problem despite Begum’s radicalization taking place in the volatile, fragmenting environment of the UK. Begum is only one among many British-born individuals stripped of citizenship since Mohamed Sakr’s citizenship was first revoked in 2009, following a trip to Somalia and suspected involvement with the militant group al-Shabaab.

Thomas Mair, a white supremacist who murdered MP Jo Cox in 2016, was undoubtedly a security threat: he was rightfully sentenced to life in prison. Yet Begum’s crimes haven’t been tried similarly. She has been used as a puppet to deflect British attention away from the innumerable problems within the UK, refocusing energy on the uncivilised nature of the non-British ‘Other’.

In the words of the philosopher Hegel, Britain is a being “which is for itself only through another”, recapturing the omnipotent British Imperial ‘Self’ in times of crisis through identifying barbarism as belonging to the ‘Other’. The Supreme Court proved once more that Britishness cannot survive without the construction of outsiders. Without displacing blame outside the UK in denial of the paradoxes of the British ‘Self’, as Marx wrote, “all that is solid melts into air”. The courts may have denied her British citizenship, but Britain will always need a Shamima Begum.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025