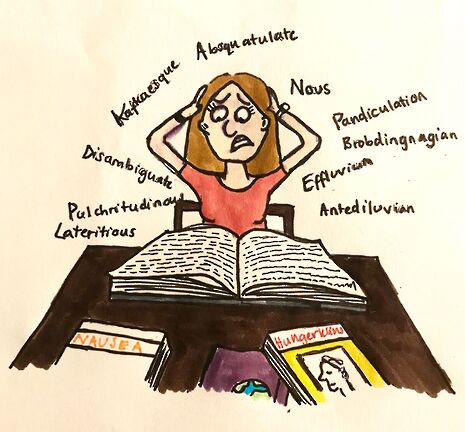

Reading lists full of convoluted academic writing are exclusionary

Aisha Niazi argues that the convoluted writing style of many academic texts can be confusing and overwhelming for students coming to university without that form of cultural capital

Before Cambridge, I always romanticised academia: a life filled with long, complex books that you somehow understood, as if part of an elite club. Once at Cambridge, I spent ages staring at the pages of Hannah Arendt, aiming to decipher them, before reverting to SparkNotes. When complaining about the density of her writings to an academic, he chuckled and responded: “I find her to be perfectly clear.” I was left wondering whether I was alone in toiling through near-incomprehensible books to get to the point.

I later discovered that my course mates also found Arendt to be a dire read. Her ideas were intriguing, but actually discovering them was a colossal task. Academic books can be sheltered from criticism in society, often seen as too lofty and intellectual to even comment on. The writing is frequently filled with jargon, which seems infallible to the vast majority of people. How can we expect students to analyse books that are written in inaccessible code?

Cambridge, or any university, should be a place where intelligent people thrive. Yet by continuing to assign masses of books that overwhelm and confuse, academics can add hours to the workload of people who generally struggle with concentration, and even more to many people with learning difficulties such as ADHD or dyslexia. This is extremely exclusionary.

If students struggle, then it must feel even worse for non-students who want to learn about intellectual topics from these sources. Academic texts are frequently presented as mysterious – so genius that only a few, great minds can truly understand them. But if this is really the case, aren’t the ideas just being poorly communicated?

Long winded, complex sentences have become an elitist tradition

Although not being diagnosed with a learning difficulty myself, I have always struggled with concentration. I often feel distanced from the knowledge being presented in these books – it is so overly complex that it doesn’t feel as if it has been produced for me. When an academic’s words aren’t engaging, it drains the excitement out of learning.

This left me with a sense of impostor syndrome: a feeling that that I wasn’t supposed to be in Cambridge as I couldn’t connect with the academic style. Finding a rare author who wrote in a more down-to-earth style was extremely encouraging. Why can’t more academics aim for this? Books shouldn’t be so dramatically distanced from how we talk in reality.

This impostor syndrome once led me to believe a career in academia was not for me. I began to view academics as desperate to peacock around, showing the variety of their feathers, continuing on a culture of convoluted debates that are separated from reality. Of course, not all of them are like this. In my experience, some do aim to make academia accessible to all, explaining concepts in simple terms and relating to their audience. I think many degrees would benefit from introducing reading that caters explanations to audience understanding – we need to make academia more human.

Ideas should be accessible to anyone with an interest in them. Some niche debates will of course require background reading, but ensuring language can be understood by a broad audience allows more people to actually learn, and more efficiently. In his book Free Will, for example, Sam Harris – a public intellectual and philosopher – writes simply, using analogies to make his point clear, simultaneously producing a fantastic reading experience. It’s incredibly short for a non-fiction piece and I found myself devouring it in a single afternoon.

Academic books might not always reach a point of mass consumption, but simple explanations of complicated ideas are often frowned upon by professors. Long winded, complex sentences have become an elitist tradition, preventing thoughts from being as easily understood or critiqued. A supervisor once told me: “we read these people for their ideas, not for their writing.” Yet I continue to read essays, articles and books from current academics that follow in the same style.

Academia has become an elite club. Students without the cultural know-how can become overwhelmed and unable to analyse these books – containing ideas they are perfectly capable of engaging with – due to overly flouncy, poor writing. Being incomprehensible shouldn’t be the aim of any writer, and writers shouldn’t target their work to an audience of fellow academics; instead, they should lay their ideas out simply so as to ensure everyone can engage with and challenge them. Thinkers must focus on making their writing accessible to anyone with an interest – not just the elite.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025