MOOC over Cambridge

Rebecca Murphy examines the next big thing in education.

Radhika Ghosal lives in New Delhi, India. Last summer, aged only 14, she completed an undergraduate-level engineering course from MIT on Circuits and Electronics. She is an example of a new type of student, learning in a completely new way. Universities across the world now offer MOOCs – Massive Open Online Courses – to anyone with internet access and the time and commitment to complete them.

The recent craze for online learning began two years ago in the USA, when Stanford University announced that three of its most popular computer science courses would be available online for free. The lecturers were stunned when over 160 000 people signed up.

Since then, MOOCs have proliferated, with several competing platforms offering online courses. The original Stanford lectures have spawned two start-ups, Udacity and Coursera, both of which specialise in teaching science and engineering. A collaboration between Harvard and MIT has also produced EdX, a non-profit provider.

The courses offered by these sites go far beyond more traditional distance-learning methods. As well as weekly video lectures, MOOCs contain quizzes and coursework exercises to keep students involved and to evaluate their progress. And the free online format is allowing people who would never normally have access to university education the opportunity to learn from some of the best lecturers in the world.

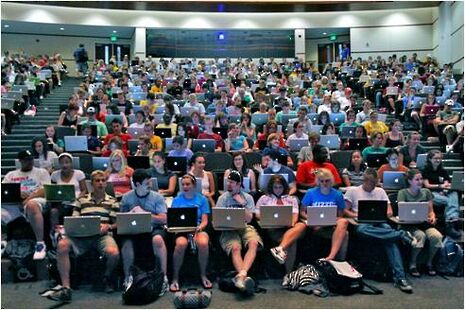

Furthermore, many students enrolled in traditional courses are also taking advantage of MOOCs offered by their institutions. Sebastian Thrun, former Stanford professor and founder of Udacity, discovered that his students preferred the online experience to a lecture theatre: “They can rewind me on video,” he explained.

Salman Khan, of Khan Academy fame, describes a similar experience. “You have this situation where now they can pause and repeat … without feeling like they’re wasting my time,” he said of his online students.

However, despite the popularity of MOOCs, not everyone is happy with the new format. Money is a major concern. Some students at American universities, where the average cost of a bachelor’s degree is over $100 000, feel “cheaped out” that their courses are offered for free online. More worryingly, investors are also concerned about the business model, neither Coursera nor Udacity has an obvious source of profit.

Despite these issues, the popularity of MOOCs is only increasing. FutureLearn, an Open University (OU) led partnership between 23 British universities, recently launched its online learning platform.

Cambridge, however, was not involved. Lord Rees of Ludlow, Master of Trinity College, has been cool about the value of online learning: “The lecturer can be replaced by distance learning - what cannot be is seminars or tutorials.” This concern over course quality belies a deeper unease about university funding. In today’s tough economic climate, universities are financed by students who pay thousands of pounds every year in tuition fees, but MOOCs are available completely free.

Jeff Haywood, vice-principal for knowledge management at the University of Edinburgh, fears that this could be “the end of the Higher Education business model as we know it.” Yet for Cambridge, ignoring the MOOC phenomenon could lead to isolation in an increasingly technological world. Haywood is resigned to the change: “Universities that don’t engage with this have got their eyes closed to the future.”

News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026

News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026 Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026 News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026 Features / Exploring Cambridge’s past, present, and future18 January 2026

Features / Exploring Cambridge’s past, present, and future18 January 2026 News / Your Party protesters rally against US action in Venezuela19 January 2026

News / Your Party protesters rally against US action in Venezuela19 January 2026