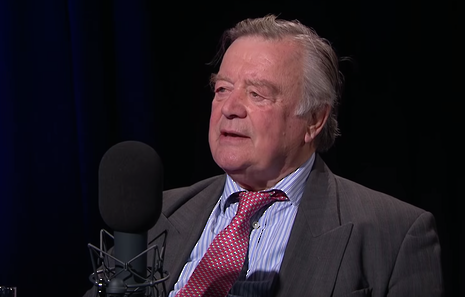

Ken Clarke: ‘The Labour Party is no longer the working-class movement it was’

Luke Graves talks to a ‘big beast’ of British politics about his working-class origins, the “social mobility problem” and what today’s politicians can do about it

Last Thursday night, four members of the ‘Cambridge Mafia’ returned to the very debating chamber they used to preside over. Lords Deben, Howard, Lamont and the political ‘big beast’ Kenneth Clarke all studied at Cambridge in the early 1960s, were all presidents of the Cambridge Union and all moved into frontline Conservative politics in the 1980s and 1990s. It was this Cambridge-educated Tory clique that became known as the ‘Cambridge Mafia’, a group that has long since been superseded by the dominance of those who studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Oxford – think David Cameron, George Osborne, Jeremy Hunt and Phillip Hammond.

They were supposed to be debating the motion “This House Believes That Debates Have Never Convinced Anyone of Anything”. As was often pointed out, it was a bit of a nonsense motion, which allowed them to regale us with personal anecdotes instead. Ken Clarke was met with warm laughter when telling the story of how, in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the impending threat of nuclear annihilation didn’t provoke wild panic or existential crises amongst students at the Union, but rather led to calls for an emergency student debate on the issue. Who says Cambridge is a bubble?

These men all moved from the halls of Cambridge to positions of great political influence, and with his booming voice, scruffy-smart demeanour and self-professed penchant for cigars, it could be easy to assume that Ken Clarke was plucked from the upper-class establishment. The reality is, however, rather different.

In his autobiography Kind of Blue, Ken describes being born “impeccably working class”. Born on 2 July 1940, he grew up near the pit village of Langley Mill in rural Derbyshire, later moving to Bulwell, a small town in the north of Nottingham. His father originally worked two jobs: as a miner in the pit, and as manager of a local cinema. After passing the 11+, he went to Nottingham High School, a private school where the local council would pay the fees for some of the top 11+ scorers (known as a ‘direct-grant grammar school’ under the 1944 Education Act), before studying law at Gonville & Caius.

“I benefited from the brief post-war period we had of social mobility. The Cambridge Mafia and all our mates were an awful lot of 11+ boys”

When I question him after the debate about selective education, he looks back fondly on his own education. He says, “I benefited from the brief post-war period we had of social mobility. The Cambridge Mafia and all our mates were an awful lot of 11+ boys.” Indeed, whilst they might not share views on Brexit and were on opposing sides of the Union debate, both Ken Clarke and Michael Howard were products of the grammar school system. From small mining community to the hallowed halls of Cambridge, you can certainly see why Ken calls the 1950s “a very socially mobile place”. Ever the shrewd politician, he is quick to temper his claim; he says there was a more limited idea of what social mobility meant back then, one that falls far short of the scale of social mobility that we talk about today.

Whilst he claims that getting through the 11+ and later going to Cambridge “transformed [his] life”, Ken says that most people weren’t so lucky. In explaining why selective education was largely abandoned, he asserts that it was “the injustice of it and the gulf between the selected few and the majority of their friends [that] was the grave weakness.”

This is a familiar argument for those, like Ken, who oppose the expansion of selective education in today’s world. His opposition to more grammar schools reflects and cements his position on the left of the Conservative Party: he’s a one-nation conservative, trying to resist the Rees-Moggian pull to the right across multiple fronts. He also went against the grain, as the only Conservative MP to vote against triggering Article 50.

“Four years in Cambridge completely changed me as a person, I suspect, and certainly my whole expectations of life”

As the Education Secretary who created Ofsted and modern-day school league tables, there was certainly a focus on trying to raise standards across the board during Ken Clarke’s tenure. Despite his efforts and those of many of his successors to make education a social leveller, he laments the state of “the social mobility problem” today. Whilst the comprehensive education system is generally of “reasonable quality”, Ken expresses regret that “the part of Nottingham I came from probably has a very low level of university admission now”.

Ken was able to emerge from a working-class neighbourhood and ascend to the loftiest heights of government. He has served three Prime Ministers and taken on roles such as Home Secretary, Education Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer, but fears these positions remain but a distant dream for a lot of those in the working-class districts that he grew up in. Writing in The Guardian in July 2016, then Universities Minister Jo Johnson claimed that whilst almost 40% of younger people go onto higher education today, only 10% of white boys from the most disadvantaged backgrounds do so.

Want to get involved with Varsity interviews?

Meet some of Cambridge's most interesting figures and ask your burning questions. Just join our Interviews Writers group or email our Interviews team to express interest.

What can be done to improve the situation? Throughout the interview Ken makes two things clear: grammar schools are not the answer, and neither is the Labour Party. He proclaims: “The Labour Party is no longer the working-class movement it was.”

On the one hand, it seemed like he may have just been trying to score some cheap political points. On the other, there seemed to be at least a sense of dismay at the current state of the Labour Party, which some see as becoming increasingly the preserve of metropolitan cliques at the expense of representing traditional working-class communities. Back in 2016, Andy Burnham, then Shadow Home Secretary for the Labour Party, was already warning that the party was struggling to connect with its heartland voters over Brexit, calling it a case of “too much Hampstead and not enough Hull” in an interview with BBC2’s Newsnight. For want of time, I wasn’t able to push Ken Clarke on how the Conservatives are trying to boost social mobility today. What was palpable, however, was his personal commitment to the cause.

I finish the interview with a question for Ken about his time at Cambridge. He candidly responds that “four years in Cambridge completely changed me as a person, I suspect, and certainly my whole expectations of life.” For him, what he acquired from Cambridge “went far beyond any academic study”.

Indeed, he seems to suggest that it was about the development of a certain mindset, an assertive sense of confidence that, accompanied by the connections he made and opportunities he was exposed to, propelled him to a successful legal career as a barrister (he was promoted to Queen’s Counsel in 1980) and frontline Tory politician. He does stress that the system has since changed; the actual degree we walk away with today means more than it did in his time. But there are still privileges conferred by attending Cambridge (their exact nature and whether they’re deserved is the topic for a whole other article), and rather than strip these away, Ken, like many others, emphasises the need to make the university “more open”, in the hope that they can be more widely enjoyed.

As I rise from the leather-bound interviewer’s chair, another journalist swoops in to ask Ken some questions about Brexit. The general form of his Brexit stance follows that of his views on access and social mobility: he regrets the current situation, but notes that “we’ve got to persevere.”

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026

Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026 Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026

Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026 News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026

News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026