Stephen Fry: ‘Looking back, we were unbelievably lucky – outrageously so’

Returning to his alma mater, Stephen Fry discusses his career, comedy, and a time when Cambridge was less pressured with Felix Peckham

The energy at the Cambridge Union is unmistakable and inexorable. You can’t help but get caught up in it. Queues to get into the chamber had started to form almost an hour prior to Stephen Fry’s arrival. I hadn’t witnessed scenes like this since the Union’s infamous puppy therapy session.

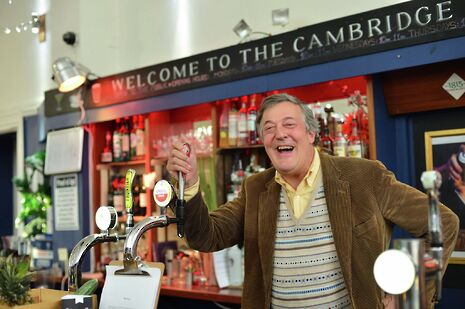

Dressed like the human equivalent of a golden Labrador, with a similarly coloured shirt and geometric V-neck sweater, Fry is a stylistic throwback to 1970s Islington, although his Apple Watch serves to remind everybody of his acclaimed adoration of technology.

Fry’s journey to becoming a national treasure, through Jeeves and Wooster, Blackadder, QI, and now as a mental health activist, is every bit as eclectic as the man himself. His path to comedic fame was never assured; at only seventeen, he spent three months in prison for credit card fraud. Laughing, he tells me that he remains thankful that he was never asked whether he had a criminal record in his interview.

Following this hiccup, Fry studied English literature at Queens’ College, of which he has “nothing but fond memories”. He proudly informs me of his enviable lecture attendance: “Hugh [Laurie] went to one lecture and I went to three, I think.” He continues: “Hugh’s one lecture became the basis of one of his sketches. He read Archaeology and Anthropology, where he had this batty old lecturer talking about Bantui huts.”

Endearingly humble, Fry explains the improbability of his career feats: “Looking back, we were unbelievably lucky - outrageously so. We saw all of the [pictures of the] Pythons on the wall… and thought, ‘That door’s been closed, that will never happen again’.”

Reminiscing about a time where Cambridge life was seemingly less pressured, Fry tells me that “there was no pressure to do exams, or get Firsts, or worry about the academic side of things. Your supervisors and the Deans said, ‘Oh, you’re really very funny! We go and see your show every other term, so you carry on doing that - don’t you worry about any of the other nonsense!’”

Pursuing this theme, I ask how much credit Fry ascribes to his Cambridge education and involvement with Footlights, to his career successes. It was “enormous”, he assures me.

“One person, on their own, is unlikely to have the confidence to believe they are funny or worth looking at. It was the fact that I did plays with Emma Thompson, and she introduced me to Hugh, and Hugh and I just naturally started to write together. But I think the most important thing is that Footlights was always about writing and performing. The two were indistinguishable; you couldn’t separate one from the other.”

Referring to the 2009 BBC series Stephen Fry in America, Fry transitions from Cantabridgian nostalgia to political commentary, offering his opinion on Trump’s ascendancy and the current narrative of political affairs.

“It’s so easy to mock Trump, for heaven’s sake – there’s never been a more obvious c***!

“The energy of globalisation and internationalism – that was huge after the Second World War. That energy was then sucked into nativism, nationalism and a hatred of corporate globalisation. And [it has also attacked] the more progressive form of internationalism, seeing it as an erosion of the genuine national characteristics and virtues of each nation state.”

Having praised the comedian and Christ’s alumnus John Oliver for his dismantling of the American political scene on Last Week Tonight, Fry dismisses some popular conceptions about satire.

“I really like the idea of satire. But most people seem to think if it as being political, topical humour. Actually satire tells the viewer that they are disgusting: ‘I am worthless; I am a hypocrite. I demand cheaper fuel for my car and, at the same time, a green planet. I am the reason the world doesn’t work. It’s not them, it’s me.’”

Increasingly animated, Fry exclaims; “It’s so easy to mock Trump, for heaven’s sake – there’s never been a more obvious c***! It’s absurd! But no one dares attack those that voted for him because it looks like snobbery.”

Finally, drawing on his experience as the President of Mind, Fry offers advice to those who may be concerned about a friend or relative, and how to approach the issue.

“There’s no absolutely standard answer. Although there are diagnoses for mental health conditions, even people with the same diagnosis are not the same. Human beings are astonishingly different.”

Although he doesn’t note it, Fry’s wit and verve is a testament to that fact

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025