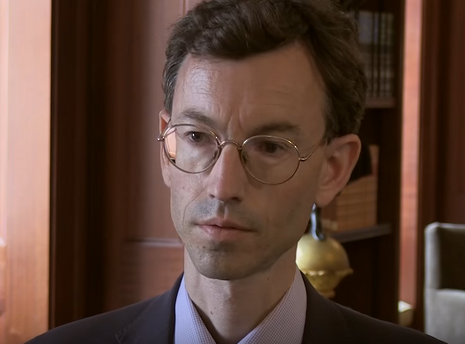

Professor Brendan Simms: ‘The US will survive Trump: my anxiety is that we won’t’

Alex King talks to noted Cambridge academic about Donald Trump, NATO and his new book

There is a deep sense of uncertainty in the world – an uncertainty about what it will look like with Trump at the helm. We hunger for information of the president’s grand strategic vision. What are his core values? What will be the role (if any) of institutions like NATO? Will the Putin/Trump bromance sour? What about China? What about Iran? Nobody seems to know.

It was understandable, therefore, that Washington insiders were apprehensive when Trump took office in January. Some of them may have hoped, however, that he would soon offer clarity. “After entering the WH [White House]“, tweeted Zbigniew Brzezinski, former National Security Advisor to former President Jimmy Carter, “Trump must give a major foreign policy speech that makes clear the new administration’s objectives and principles”.

A month later, the White House was all havoc. First, there was the diplomatic grenade that was the Muslim ban. Then, having called NATO ‘obsolete’ during Trump’s campaign, his team were in Europe claiming that ‘The United States of America strongly supports NATO and will be unwavering in our commitment to this transatlantic alliance’. And having talked tough on China, Trump suddenly seemed to accept its claims to hegemony in the South China Sea. Brzezinski’s hopes of clarity had been dashed. “Does America have a foreign policy right now?” he tweeted in disbelief.

I repeat this tweet to Professor Simms. “That’s a really interesting question. The simple answer is we don’t know”.

One of the most striking things about Trump’s presidency, he comments, has been “the tension between the different parts of the administration”. Factions continually vie for the ruler’s attention. “We’ve got very much countervailing noises coming from the White House itself”, Simms remarks. What else would you expect other than a lack of coherence when it comes to strategy?“These things are always much discussed,” Simms admits. But it is “really the subject of a lot of tea leaf reading”.

But there is something to more to the tweet, Simms suspects. Brzezinski seems to imply that Trump is making it up as he is going along, opportunistically telling his supporters what they want to hear – nonsense, Simms says.

“To be absolutely clear, NATO is in a far worse position now than it was before Donald Trump became president”

‘The convictions that leaders have formed before reaching high office’, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger remarked in 1979, ‘are the intellectual capital they will consume as long as they continue in office’. I ask Simms how this quote, which he and Laderman use to preface their book, relates to Trump. “You obviously have to stretch the phrase ‘intellectual capital’ a bit when you’re dealing with Trump,” he wryly points out. “But the point that Kissinger was trying to make was that, once you are in office, you have very little time to learn on the job”. The same goes for Trump (who, by the way, as one of the oldest US presidents in history, has had more time than most to acquire a worldview).

Laderman and Simms attempt to show the intellectual origins of ‘Trumpism’, and demonstrate how consistently Trump has been making his case for ‘America First’. Central to his worldview is the notion that the US just doesn’t ‘win’ anymore. Once a burgeoning economic and military superpower, America was now being ‘ripped off’ by its ‘so-called allies’.

On 2nd September 1987, Trump bought out an advertisement in the Washington Post in which he criticised US foreign policy in the Iran-Iraq War. The US had expanded its naval presence in the Middle East to ensure the continued flow of oil to Europe and Japan: “The world is laughing at America’s politicians as we protect ships we don’t own, carrying oil we don’t need, destined for allies who won’t help”.

Germany is also on Trump’s list of targets. In an interview with Larry King in 1999 on CNN, he talked of it ‘ripping [off]’ the US. Today, Trump is very critical of Germany’s economic protectionism, claiming in a Times interview on 16th Jan 2017 that the EU was ‘basically a vehicle for Germany’. Laderman and Simms, therefore, show how there is some consistency in what Trump is saying.

In an interview with Rona Barrett in 1980, Trump stated that his personal philosophy rested on seeing ‘life to a certain extent as combat’, revealing a realist perspective on international relations, in which the world is anarchic and strength is paramount. To Trump the businessmen, it doesn’t make sense for US allies to profit from American protection while contributing nothing themselves. This was a bad deal for America – it would need a better one.

“The problem may not be the wars [Trump] starts, but the ones he is not willing to fight”

Trump’s solution for the last thirty-five years, Laderman and Simms demonstrate, has been for the US to look after its own before anyone else. ‘It’s time for us to end our vast deficits’, he insisted back in 1987, ‘by making Japan… Saudi [Arabia], and others pay for the protection we extend as allies’. This is rather consistent with Trump’s stance on NATO today. ‘I want to keep NATO, but I want them to pay,’ he told a rally in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in July 2016. America comes before anything else for Trump. ‘Americanism, not globalism, will be our credo’, he declared last year.I ask Simms whether it really matters that Trump had been articulating a consistent message. After all, the realities of politics mean that he will not deliver on his promises to put ‘America First’. Simms sees it differently. “To be absolutely clear, NATO is in a far worse position now than it was before Donald Trump became president”.

I cite the Munich Security Conference last month as evidence of Trump’s U-turns. It had been here that Mike Pence, Trump’s VP, had announced the US’s ‘unwavering’ support for the EU and NATO. Incidentally, Simms had attended the conference. Although Pence’s statements were designed to be conciliatory, he did not take questions from journalists after speaking. This was because, Simms suspects, he couldn’t provide an answer to the question on everyone’s mind: does the Donald agree with you? Laderman and Simms are sceptical that Trump will ever U-turn on NATO.

So what is in store for Trump’s world? I ask Simms. He paints a bleak picture. Safeguards built into the US constitution will function to check Trump’s power at home, he explains. “The US has proven itself to be a resilient democracy – they will survive Trump”. Simms pauses. “My anxiety is that we won’t”.

He explains that “the problem may not be the wars he starts, but the ones he is not willing to fight”. Everything points to protectionism, and American secession from the global system. A new “Yalta conference” beckons, in which the United States would concede a “sphere of influence” to Russia in return for stability in the Middle East. Trump will demand more money from NATO allies, impose tariffs on importing manufactures into the US, and get tough on China.

To be sure, there is still much uncertainty. Perhaps Trump’s bark is really much worse than his bite. Nonetheless, Simms says apprehensively, “I think we’re in for an extremely bumpy ride”

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025