Long Read: ‘For a lot of people, what’s invisible doesn’t exist’

Anna Menin speaks to the student behind The Pittingdon Club, a group for women at Oxbridge who are “tired of collectively maintaining a stiff upper lip” about sexism

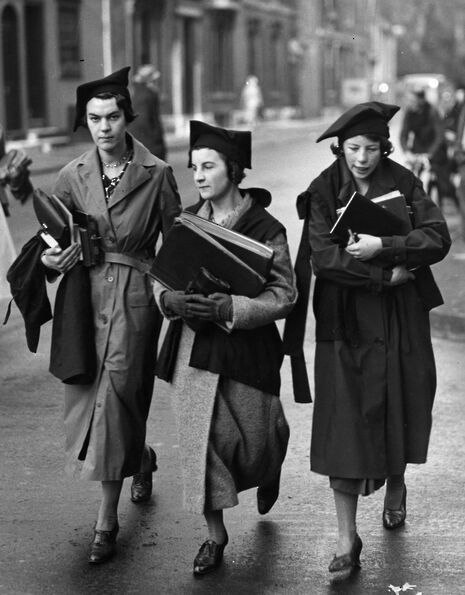

In 1897, a discussion took place in Senate House: should the University permit female students to receive full degrees? As fellows and dons debated in the chamber, a group of male students began to form in protest. They assembled outside the building which now hosts the University bookshop in boater hats and suits, bearing banners reading “No gowns for Girtonites”.

The protesters hoisted an effigy in front of the building, hanging it over the cobbled streets: a woman, in a white dress, riding a bicycle.

The motion failed, and the group lowered the effigy to the ground. Jubilant, they tore it apart, and marched down King’s Parade to stuff its remains through the gates of Newnham.

Nearly 120 years later, such overt and frenzied displays of sexist behaviour are, mercifully, much rarer. But sexism, albeit mostly in more subtle forms, is still rife at Oxbridge. Unable to just stand by, Rebecca, an Oxbridge postgraduate student, founded The Pittingdon Club, a Tumblr and Facebook page for women at the two institutions to post their “gripes with the system and the people within it that perpetuate the issues that continue to hold us back.”

“It’s been a long time coming”, says Rebecca, when I ask about the creation of the page. “I founded it after a lot of conversations with people about the same sort of thing over and over again, the same sort of issues at all levels of their academic careers. It’s not just something that undergrads, postgrads, or fellows experience: it’s across the board, and very pervasive.”

It was this growing frustration, coupled with the experience of being sexually harassed by a man at her university for over a year, that led her to create The Pittingdon Club. “I got so mad that I wanted to type out my frustrations somewhere, and then other people said that they wanted to type out their frustrations, and now we have a frustrations page”, she explains.

The page takes submissions from women at both institutions, and has so far posted examples ranging from female academics being overlooked by their peers and superiors, to instances of alleged physical assault.

Rebecca readily acknowledges the work Oxford and Cambridge are doing to “counteract” sexism, and on Wednesdays, the Club posts examples of good deeds done by men, that “have made us feel safe and respected here.” However, despite these “positive changes”, she still sees “so much” of the legacy of a time, not so long ago, when the effigy of a woman could be torn apart in the heart of Cambridge.

“It just kind of still remains an old boys’ club overall”, she sighs, “and it’s not like women can join The Pitt Club and The Bullingdon Club” (The Pittingdon Club’s name is an amalgam of Cambridge’s and Oxford’s most notorious ‘dining clubs’). “There’s just so much that’s ingrained in [Oxbridge] that makes it a very hard thing to tackle… it’s in the foundation.”

Yet these issues, however ingrained they may be, are not always readily apparent. I ask Rebecca how she thinks this should be addressed. “There needs to be more awareness raised of the fact that these things are still going on”, she replies. “I think for a lot of people, what’s invisible doesn’t exist, and if it’s out of their realm of awareness… they think that you’re making a big deal out of nothing.”

Rebecca sees simply drawing attention to the reality of women’s experiences at Oxbridge as the Club’s fundamental purpose. She fears that, “after a while”, female academics simply begin to accept instances of sexism as “part of the career” – “if you’re a woman in academia, you’re going to be experiencing this, so you just grin and bear it,” she told me.

“I don’t think that that’s how it should be.”

Part of this, she argues, is rooted in the fact that “academia is so heavily focussed on intellect”, and “because women were always historically seen as ‘feeble-minded’, unable to wrap their minds around the concepts of academia, and because so much of the history of the universities is rooted in that, it just continues to pervade.”

Having done her undergraduate degree in the US, Rebecca has a different perspective on those manifestations of gender inequality specific to – or at least more common at – Oxbridge.

“I know it’s different everywhere, and I know for a fact that there’s a lot of horrible stuff going on in America right now”, she acknowledges, “but I feel like that’s often frat boys pulling stunts, or the odd professor being inappropriate”, whereas “here, there are some fellows that I feel like I can’t even talk to because I’m a woman.”

“They completely disregard my opinion,” she continues, “and I had never had that happen before. Even if the men in America were sexist or inappropriate, I never felt like they would just completely discount everything I was saying because of my gender.” Her frustration at this is evident, yet she once again stresses: “I don’t want to make it sound like it’s everybody, because it’s not”. However, she tells me, it remains “a big enough problem that a lot of people have noticed.”

“We just have all of these assumptions that get built into us as we grow up, regardless of our political beliefs,” Rebecca says, citing internalised sexism as an example. “We have to un-learn them as a process, and that’s quite a struggle, especially if you grew up and went to Eton, went to Oxford or Cambridge when it was all Etonians, and now are a distinguished fellow there.”

That brings her on to another way in which the immensely male-dominated history of Oxbridge can manifest itself harmfully, as she talks about the negative impact of “all of the male portraits in the dining halls, all the male portraits everywhere. Being in that sort of environment leads to worse performance by people who aren't well represented.”

“If all you see is white men, and you’re not a white man,” she continues, “it’s very easy to internalise the idea that you don't belong here, and that this isn’t a place for you, and I do think that that sort of discrepancy can carry through in tangible things like exam results.”

Yet, despite all of this, Rebecca does not believe that overall, Oxbridge is an “unsafe” space for women. “I just think that there are a lot of very subtle things that are part of the culture that make it a challenging space to exist in as a woman, that are just so pervasive in everything… especially if you feel like you have nobody to talk to about that kind of thing.”

This is, of course, what she intends The Pittingdon Club to be. I ask what her hopes for the page are.

“I would be nice if this got picked up, and taken far enough to actually create some sort of sustainable change, but I’m not under any illusions that I’m that important,” she laughs.

“Let’s just hope that something brings attention to it… and we can finally get something that would make life a lot easier for a lot of people. One of the things to keep in mind is that even if you don’t need to use it, just knowing that that option’s there is really helpful. Knowing that there’s something in place to protect you can be so psychologically powerful: not only does it make people who feel like they could be potential victims feel safer, but it also would stop potential aggressors from aggressing, and I don’t see why we can’t have that.”

Finally, I ask Rebecca about her decision to remain anonymous, assuming she wanted to avoid the online harassment and abuse that is so often directed at those who campaign against sexism. However, it was not that simple: “whatever, I can handle abuse,” she shrugs. “Enough people have sent me nasty messages or said nasty things to my face that I can give some snarky responses or ignore them, however I choose to deal with it.”

Instead, it was concern about the number of people who warned her that “universities like this are more happy to jump to boxing somebody out than listening to their concerns,” that led to the decision.

“I don’t want my career to be ruined, and I don’t think it will be, but because so many people warned me about that, I thought maybe I should pay attention. I didn’t want my life to get harder just because I started a page, just because they didn’t like what I was doing.” She also does not want The Pittingdon Club to overshadow her research, and is keen to stress that “what I’m doing as a career isn’t gender studies; I’m not even in that department or at all connected to them.”

“It’s just something that I’m fed up with, as are a lot of people, some of whom are in gender studies, some of whom are not, because it’s everybody,” she adds. Another factor was her frustration with the fact that “once you ‘come out’ as a feminist, or anything like that, it becomes your only label”, and a desire to avoid this reductive treatment. Once again, she stresses: “this has nothing to do with my research. This is my life.”

Names have been changed.

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026 Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026

Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

![How to Create an Attractive Freelancer Portfolio [5 Tips & Examples]](https://www.varsity.co.uk/images/dyn/ecms/320/180/2026/02/vitaly-gariev-ho2tNOWZYXM-unsplash-scaled.jpg)