Did you hear that correctly?: Music and emotion

In her last column of the series, Juliet Firth discusses the sometimes oblique relationship between music and human feelings

‘Happy Hits,’ ‘Sad Songs,’ and ‘The Stress Buster:’ just three of the numerous auto-generated playlists on Spotify in the category ‘Mood’. It seems so easy to use music as an endorphin-fuelled antidote to daily encumbrances. And yet, these playlists feel generalising, as it is fundamentally impossible to accurately reflect every emotion that we might have and, therefore, immediately scratch every emotional itch we might conceive. Emotion in music is such a personal part of our individual listening experiences that it’s no wonder why this topic is so popular in psychological research. In this final article of the series, I'll explore the ways in which we are emotionally attached to music, how emotion is expressed by music, and how we react to it.

It is important to distinguish emotion portrayed by the music from our own emotional reactions to it

Explaining emotion in music is simplified from the outset. ‘Major equals happy, minor equals sad’ is a typical offender within the educational system. Before the 20th Century, the understanding of music in relation to the key that it’s in was, arguably, integral to the listening experience. A list of keys and their characteristics was published in 1806, in Christian Schubart's ‘Ideas towards the aesthetics of music’ and composers and audiences alike from around 1700 to 1900 would have been fully aware of what each key ‘represented’, affecting their perception of the emotions conveyed through the music.

Examples of these range from C major described as ‘completely pure’ and associated with ‘innocence’ and ‘simplicity’, Eb major as the key of love and devotion, to Ab major as ‘the key of the grave’. Notice that all of these keys are major, and yet so disparate in the emotions and soundscapes each aims to portray. How can the catchphrase ‘major is happy’ possibly encapsulate the many nuances that were once understood from each key? To find out how emotion and music intertwine, it is important to distinguish emotion portrayed by the music from our own emotional reactions to it.

How can the catchphrase ‘major is happy encapsulate the many nuances that were once understood from each key?

Let’s begin with expression of emotion. Studies suggest that the emotional depth of a piece of music is caused by four combined factors; structural, performance, listener and contextual features. Structural features are the emotions evoked by purely musical elements, split up into segmental features (sounds, tones and pitch) and suprasegmental features (melody, tempo and rhythm). Our brains might make the connection that a fast tempo evokes excitement and that dissonant harmonies indicate anger, although these clichés are not entirely universal.

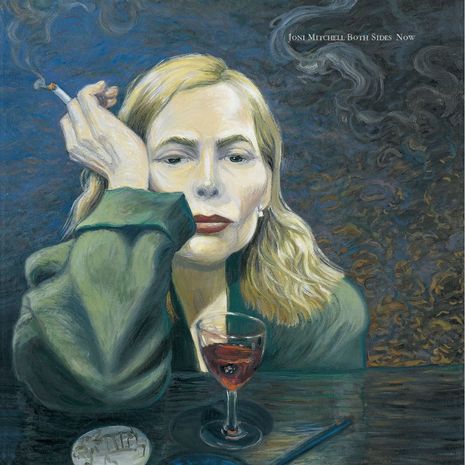

Listener features involve the identity of the listener, including age, personality, knowledge of the music and willingness to listen. Contextual features take into account the occasion and location where the music is played. Performance features focus on the skill and appearance of the performer (if that is applicable) and can make a large difference to the emotional expressiveness of a piece of music. A good example of this is Joni Mitchell’s recent version of ‘Both Sides Now’ from her album ‘Clouds’, first released in 1969 and re-released as part of her album ‘Both Sides Now’ (2000). The sagging tempo and weakening vocals change the emotional intent: she is no longer maturing through growth and self-discovery but is now a wistful elderly woman, viewing her life in retrospect.

Next time you watch an advert, pay attention to what music is being played and how this affects how you feel, maybe even about that particular product

When we listen to music, our whole brain is activated. The parts responsible for emotion, creativity and even motor functions are triggered, which is why listening to music has the ability to recall specific emotional memories, evoking nostalgia. In Juslin and Västfjäll’s 2008 publication “Emotional responses to music: The need to consider underlying mechanisms”, the ‘BRECVEM’ model is established which outlines seven different ways that music elicits emotion in the brain. The ones that particularly interested me were ‘VEM’: Visual imagery, Episodic memory and Musical expectancy. To try out ‘Visual Imagery’, listen to a piece that you’ve never heard before and shut your eyes. Does a picture come to mind and does this picture make you feel a certain way?

This reminds me of an activity at primary school, when the teacher would put on a song or piece and we’d have to draw a picture of whatever the music conjured up in our minds (although, I’d often cheat and just draw a stage with a band performing on it). In imagining a scene, we may begin to experience ‘Episodic Memory’ which is when a particular piece of music reminds you of a certain experience in your life, evoking certain emotions wrapped in nostalgia. My drawing of the stage might be a recollection of a particular concert that I had been taken to. But, if what we are listening to then breaks away from what we expect, and instead launches into some new remix, that’s when we might have the emotional response of disappointment from incorrectly foreseeing the next verse or, conversely, it does exactly what we expect and we are therefore satisfied as a result: either way, ‘Musical Expectancy’ can provoke an emotional reaction.

Next time you ‘absolutely must hear’ a certain song, think about why you feel that urge

The ability to conjure emotions through the use of music is a highly persuasive tool that has been used by composers for centuries, even to the extent of purposefully manipulating the listener. Next time you watch an advert, whether it be on the television or YouTube, pay attention to what music is being played and how this affects how you feel, maybe even how you feel about that particular product. Music enhances memory, so if you were to hear the music used out of this context, it is likely that you will remember the advert, as I’m sure you have experienced before.

Learning to play a musical instrument is such a bizarre and yet highly esteemed hobby. But you don’t need to learn an instrument to feel an emotional bond with music. The urge to listen to a particular piece and the urge to play an instrument both stem from an urge to satisfy or express certain emotions. So, next time you ‘absolutely must hear’ a certain song, think about why you feel that urge, why you might want to attempt to replicate it, why you might yearn to create. We all have the ability to allow music to have prominence in our lives, as indeed it already does for many of us, whether we are aware of it or not.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026