Nick Drake: River Man

Uncovering the life of one of Cambridge’s most overlooked folk sons

Cambridge, I often find, is a contradictory place. Physically nothing more than a mass of old, dusty books and buildings, it somehow acts as a wellspring of discovery, from which new theories and ideas perpetually seem to appear. This paradox, in turn, manifests itself in its occupants, whose own identities seem almost parodical to the outsider, the charade of formal gowns perhaps being the most pertinent example, ceremonial dress for what is essentially, as my friend once described it, nothing more than “glorified pres”. From Byron to Darwin, Cambridge’s history is littered with contrary characters and yet fewer are more opposite or more overlooked than Nick Drake.

Given his recent induction into the Folk Hall of Fame and the approach of what would have been his 70th birthday in June, it is well worth delving into the Nick Drake legend to uncover the story of undoubtedly one of Cambridge’s most forgotten sons. Unknown to the majority of Cantabrigians, he nevertheless inspires a cult following amongst his fans – to quote my Director of Studies, he was “just a genius” and I once, after a heavy Life sesh and while winding down to Drake, had a neighbour knock on my door, not to ask me to keep it down but instead whether he could come in and listen too. At first glance little more than another stereotypical 60s counter-cultural figure, looking below the surface of Drake’s story reveals a much more complex and troubled personality.

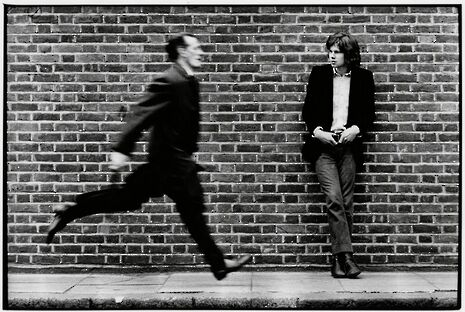

An English student at Fitz from 1967 to 1969, he came from an upper-middle class colonial background (he was born in Rangoon) and seemed very much a product of his class and times. Attending Marlborough public school as an adolescent, Cambridge was doubtless seen as the natural next step, before moving onto greater things. An accomplished sprinter and first-team rugby player, Drake appeared the archetypal offspring of colonial gentry, practically falling straight from the stanzas of Rudyard Kipling’s ‘If’. However, this had begun to change following his 1965 purchase of an acoustic guitar and discovery of Bob Dylan. A year prior to his arrival at university, he spent a gap year busking in Aix-en-Provence and began experimenting with drugs, as well as beginning to write his own songs. It was at Cambridge though, away from the sun-soaked streets of the French riviera and by the wholly more English (see wetter) banks of the Cam, that his musical talents really began to blossom.

If there is one thing that defines Nick Drake’s music, it is its quintessential Englishness. Despite his undeniable American influences, the lyrics are full of the rural romanticism of traditional English literature. With the family home at Tanworth-in-Arden in Warwickshire, Shakespeare’s own county, and Drake himself studying the English canon at Cambridge, one of England’s most historic cities, the full weight of years of preceding poetry and prose seeps into his verses. Album titles such as Bryter Layter seem to recall an older, more Chaucer-esque form of spelling and song titles such as Fruit Tree and Man In A Shed evoke pictures of flowerbeds and orchards, a far cry from the palm trees and LA casinos of his contemporaries across the pond. Indeed, it is the oft-romanticised Cam that provided regular inspiration to Drake, as he strolled along its banks from his accommodation on Carlyle road into town.

It is an influence most evident on the song ‘River Man’, from Drake’s first album Five Leaves Left. Accompanied by orchestral strings akin to Delius, Drake strums along in 5/4 time and speaks of a girl called Betty, perhaps an allusion to Wordsworth’s poem ‘Idiot Boy’ featuring a character of the same name.

However, other things lie below the surface, in particular the first indications of Drake’s melancholy and struggles with mental health. Singing “about the ban on feeling free”, this would be a tone that would consume Drake and his music, music in which he battles to reconcile his own personal problems with the world. Disillusioned with Cambridge, Drake would drop out nine months before graduation to pursue music full-time.

Of the three albums that followed, Five Leaves Left, Bryter Layter and Pink Moon, none sold well, largely slipping through the cracks of the British public’s musical attention. Despite this, music critics were largely favourable, with John Peel being notable among his fans and inviting him to perform on his radio show. Caught between praise and a lack of commercial success to show for it, Drake’s mental condition worsened, slipping into depression and by 1971 he had been prescribed antidepressants. It is a frustration encapsulated in his song ‘Black Eyed Dog’, the dog being a metaphor for his depression. According to his producer, Joe Boyd, Drake said that “I had told him he was a genius, and others had concurred. Why wasn’t he famous and rich?”, a particularly tragic remark given his later success (all three studio albums are now certified gold).

Drake died on the 25th November 1974. He was 26. Found lying unresponsive on his bed in his childhood bedroom by his mother, he had overdosed amitriptyline, the very antidepressant that had been meant to save him. It is unknown whether it was suicide or accident. Never a Jim Morrison or a Hendrix, Drake did not even live long enough to join the dubious ‘27 club’ of musicians, a reflection of his isolation from the fame that themselves received and that he, sadly, did not.

Yet to tar him with the same brush as other, wilder legends would be to do him a disservice. Nick Drake’s music is uniquely his own, light, gentle and calming in spite of his own personal problems. Caught between the counter-culture of the sixties and a more traditional England, neither he nor his music ever quite found, to quote the man himself, their own “Place to Be”. And yet, that is possibly what makes it all the more beautiful.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026