Punk, pussy, protest; activism, anarchism and afrobeat: music at the centre of revolution

Thea Sands explores music in revolt 100 years on from the Russian Revolution

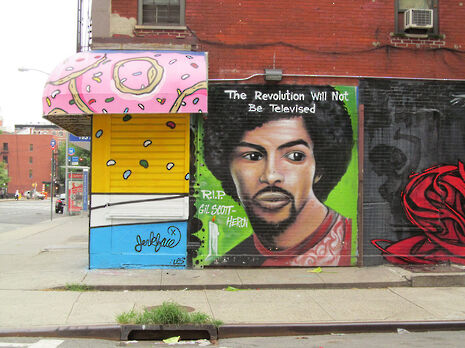

“The revolution will not be televised… The revolution will not go better with Coke. The revolution will not fight the germs that cause bad breath. The revolution WILL put you in the driver’s seat.”

As Gil Scott-Heron reminds us… the revolution is present in sound. The revolution will be listened to.

Sound is a tool. The superglue of society, capable of uniting the masses in force. A hammer always there to ring the dismal death knell for the corrupt crooks of our society. The sirens of injustice always wail out against human misdealings.

In the one hundred years since the Russian Revolution raged through music, art, theatre, and culture, we’ve seen punk, Afrobeat hip-hop, and rock n’ roll pushing through political oppression and dissent. Like Russian composer Dmitry Shostakovich, who weaved a dissident voice through his music, other composers have followed suit, contributing to the musical uprising and reacting to the perils of revolution with social commentary. After the end of tsarist rule and Stalin’s communist contamination, there was an artistic revolution, tied to the politics of opposition, spurred on by a yearning for the new. Constructivism built the foundations for abstraction, brutalism, pop art, postmodernism, and punk, and the actions of composers inspired by these movements can be traced through to the punks of our age.

After the rock n’ roll hurricane ripped through the US in the 1950s, a tsunami of political protest, psychedelic drugs, and sexual liberation engulfed parts of the world in the 1960s, with The Beatles in the eye of the storm singing about revolution. But Iceland remained an isolated land. Parched by prohibition, with a few drips of culture only just seeping into its soil, the hurricane was revived in the 1980s by the crash-landing of punk’s galactic ship, with Captain Björk and comrades from Sigur Rós aboard. Spurred on by cheap home recording technologies, they formed a makeshift musical heritage for the island. Such formation of identity with protest is exactly what Russian feminist band Pussy Riot’s music-led stunts helped to foster. Their action of storming Moscow’s Christ the Saviour Cathedral in February 2012 to ask the Virgin Mary to expel Putin connects to Shostakovich’s grotesque portrait of Stalin, present in the second movement of his tenth Symphony. Pussy Riot functions as a blockade. Their radical acts are the ‘sound sandbags’ preventing the flood of totalitarianism and the drowning of democracy.

Similar themes can be found in the works of British composer and enfant terrible Cornelius Cardew. Cardew was a committed Maoist who believed in uprising and worldwide proletarian revolution. He wrote overtly social and political songs and piano music like Revolution Is The Main Trend in the World Today. Yet his biographer John Tilbury writes that “his music is… too artful ever to be useful for socialist revolution, and too artless to be…art”. Cardew’s political commentary smacks of the same disdain found in Billy Bragg’s songs. The lyrics of Cardew’s Smash the Social Contract seem to hold particular relevance to our current political predicament: “For the ruling class and labour Government the situation is getting worse and worse/ Ev’ry thing they try is bound to fail because they ‘Labour’ under history’s inescapable curse: From crisis to crisis they lurch and they sway/ They scratch their heads to find a new devious way…”

One thing unites Pussy Riot, Cornelius Cardew, and even Cassetteboy: their protest against misuse of authority and their use of music and words to engage the masses.

However, a different type of revolution was born out of the machine age. Radical new “art in the age of mechanical reproduction”, as Walter Benjamin put it, ushered in the era of synthesisers, sampling, and the symbiosis of music and politics. Scott-Heron’s 1970 track The Revolution Will Not Be Televised amplified the black civil rights struggle and the sickeningly, synthetically sweet obsession with pop culture that saturated the masses in the US. His music was a key precursor to hip-hop – the grandfather of Kendrick Lamar’s politically charged To Pimp A Butterfly and DAMN. Similar sentiments filter through Afrobeat legend Fela Kuti’s music. With twenty-six wives and a rebellious agenda, Kuti’s impassioned music, a fusion of traditional African rhythms with American jazz and soul, riled against the Nigerian government’s spurious value system, as explored in his song Zombie which highlighted the brutality of Nigeria’s military regime in the 1970s.

Fela Kuti’s voice traces into hip-hop, but his son Femi believes artists hold a less political stance today, musing that “if the younger artists were more political, probably we would be at war.” Yet I believe this isn’t a case of ‘depoliticising’, but a change in how music is used in revolution: to avoid conflict and war and unite instead. The Egyptian Uprising of 2011 saw artists spreading their revolutionary messages on social media and public platforms, as with the Egyptian rapper Ramy Essam’s Leave, which fused the chants and slogans on the street of the revolution into an aural symbol of the uprising in action and which played out from the stages of Tahrir Square’s tent villages on the hour. Music is always at the centre of change.

The revolutionary organism of sound is alive and roaring, and even a century on from the Russian Revolution it is continuing to be a vital mechanism for change. As punk and hip-hop contest corruption and oppression, it’s down to the listener to amplify the cacophony of disdain and rise up together in a choir of the revolution. Keep making noise

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026