Chemistry revision in custody: meet XR’s student activists

From glueing themselves to pipes to being strip searched by the police, Iona Tompkins finds out how student activists are taking on the climate crisis

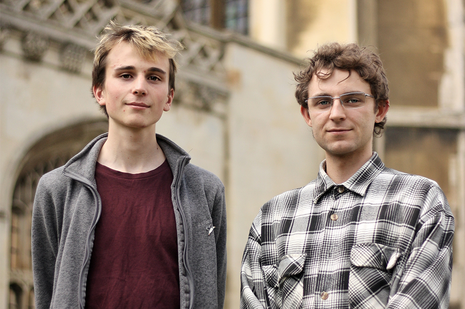

Poised. Measured. Articulate. Perhaps not the first three words that typically spring to mind when thinking about Extinction Rebellion (XR) protesters. But when I meet Cressie, Joel, Will and Joey, Cambridge students and XR activists, they’re the only ones that feel right.

At 6am on April 11, 40 XR protesters jumped the fence of an Essex petrol station, climbing onto the roof and attaching themselves to one of the pipes. Cressie, Joey and Will were among them, grinding production to a halt for well over twelve hours: “no trucks could come through until the police started putting up ladders to get us down”. All three were subsequently arrested for their actions.

“We had a Disney sing along. One guy was doing his chemistry work”

The atmosphere sounded somewhat surreal. “We had a Disney sing along. One guy was doing his chemistry work”. Joey was finally arrested at 9pm, whilst Cressie stayed up on the pipe overnight. The protesters do everything they can to make it as hard as possible for the police to bring them down, including supergluing themselves to each other and the oil pipe. As Joey puts it: “climbing up a ladder to bring someone down is difficult ... but getting a team that knows how to do that and how to cut someone’s hand out of super glue is doubly hard. It took them twelve hours to get me down”.

After twelve more hours in custody, the protesters were released and picked up by Trudy (“sixty-eight, a lovely lady with a car and some snack bars”).

As Joey talks through a typical action, I’m struck by how vulnerable the group render themselves during these protests. Some have to climb down early because of crippling vertigo, and they have to place complete trust in the police not to abuse their powers of authority — all whilst superglued to a highly flammable oil pipe.

But why put themselves through this? Cressie, Joey and Will were all arrested as part of XR’s Just Stop Oil Campaign, which aimed to cause “material and economic disruption”, in order to put pressure on the government to renege on their commitment to building six new oil structures in the North Sea. The group is at pains to highlight that the government is “sabotaging the UK goals to carbon net zero”.

In stark contrast to Good Morning Britain’s recent explosive interview with XR activist Miranda Whelehan, these activists are steadfastly composed, emphasising that their demands are “in line with the science”.

When asked about the perception of XR as a middle-class movement, Cressie accepts that there are indeed “a lot of privileged people in the movement”, but emphasises that this privilege is being acknowledged. “It’s being used correctly, and to create positive change”.

Indeed, this reputation gives them a form of protection: “it’s very well known that if you’re a person of colour, you’re more likely to be treated badly or worse by the police. And that has to be acknowledged”.

The importance of having other, less visible roles becomes clear when Will explains how they have “experienced verbal transphobia from the police”, and that whilst they are “able to deal with that”, the fact that not everyone would be “has to be acknowledged”. They emphasise that there are “many other roles people can play in the movement” that are less publicly visible but nonetheless remain crucial to the smooth running of their activities, such as the police station support that Trudy provided after the group’s most recent action.

The police’s powers once the protesters are in custody also leaves transgender activists particularly vulnerable to discrimination. Strip searches, they say, are part and parcel of the detention process. “When you’re in custody you’re under [the police’s] duty of care”. But this doesn’t stop the experience from being a “traumatic” one — some protesters are as young as 15.

Given the accusations of vigilante narcissism or martyr-complexes that have followed some media coverage of the movement, are the group aware of how their actions may be perceived by the unconvinced? Cressie admits that at their most recent action, many oil plant workers were initially hostile to their cause, “verging on aggression”. However, after a protestor trained in de-escalation explained that the protests weren’t aiming to target workers personally and apologised for them being “caught up in it”, the situation “calmed down a lot”.

Despite her calm tone, Cressie’s frustration at the media’s attitude is clear. There is “only so much that protesters on the ground can do” to counteract a narrative that is upheld by multi-billion pound media conglomerates.

Do these incidents ever mean they regret their involvement? “Never”. Though Joel admits he still flinches when he sees a police car – “they do the intimidation quite well”.

Having taken up over an hour of the group’s time, we begin to conclude. As a fourth-year engineer who’s spent his holiday glued to an oil pipeline, I’m sure Joey has far more valuable things to do with his time than talk to me. Before we disperse, I ask one final question: Where next? Graduation looms for some, and the combination of Cambridge degree and a criminal record remains a fairly unusual one.

“I can’t imagine what kind of a career I will have because at the moment I have no idea what the world is going to look like”

Joey wants a job where his work can have a real “impact on this issue”, with a company that won’t be deterred by his criminal record or continuing activism. For Cressie, however, the future feels more unstable. “I know this is going to sound quite sad, but I can’t really imagine what kind of a career I will have, because at the moment I have no idea what the world is going to look like when I am at the stage where I’m looking for a career”.

Despite the somber nature of her words, Cressie’s tone feels more pragmatic than fearful. As we pack up, I wonder out loud how the group stops climate anxiety from paralysing them, as it often does for many others.

“What’s that phrase?” Cressie says, pausing slightly. “‘Despair breeds inaction and inaction breeds despair.’ Through taking actions you meet like minded people, and realise this is something that so many individuals are concerned about”. Joel echoes her sentiments: “it takes energy to be anxious, and it’s really powerful to use that energy and then redirect it towards action”.

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026

Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026