“A long-term optimist”: Peter Frankopan on staying resilient during the pandemic

Nick Maini speaks to the Silk Roads author about what COVID-19 means for globalisation, China and his position as an academic

Typically, our interviews are conducted in person. They take place immediately after a Union debate, with the speaker coming out of the debating chamber, eager to get to the bar where ensuing conversations often drift late into the night. Like many aspects of life, however, the current pandemic has disrupted this normal state of affairs. So, when I saw that an individual who I was keen to get hold of was due to speak at a Union debate – Does coronavirus show humanity at its best? – instead of hurrying to the debating chamber, I fired up my laptop and followed a link to watch the event on Zoom, globally live streamed via YouTube.

On this occasion, the standard Thursday night debate structure was replaced by a general discussion panel, intended as a ‘less confrontational’ format for exploring the moral dimensions of the pandemic. The current President of the Union, Adam Davies, appeared in black tie and beamed as he introduced each of speakers, who, in turn, appeared on the screen, each in various states of dress and undress, and each sat in a different space, ranging from the kitchen table, to studies and even bedrooms.

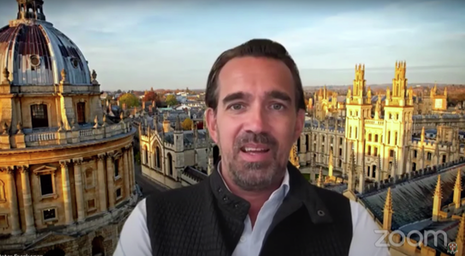

Frankopan was invited to speak first. His background had been digitally substituted for the dreaming spires of Oxford and he was sporting a sleeveless Nehru jacket. He was also donning the beginnings of a beard, giving the impression of an older and sager figure than I was accustomed to seeing. I wondered whether he was making the transition from the dashing, Tintin-esque explorer of the Silk Roads to a more retiring, talking-head professor but concluded that it was probably just a lockdown respite from shaving. Frankopan is a powerful rhetorician and as he laid out his case, he demonstrated the enviable ability to spool out profoundly insightful sentiments, seemingly at will. Yet Frankopan is an understated, unpretentious individual who cloaks himself with the humble mantle of English self-deprecation.

After the debate, I soon discovered that Frankopan can be a difficult man to pin down. Although his remit is purportedly academic – he is currently serving as Professor of Global History at Oxford and holding tenure as a Senior Research Fellow at Worcester College – the enchanted intellectual existence he leads in Oxford is only a single strand in the complex tapestry of his life. In reality, his responsibilities extend far beyond Oxford to encompass philanthropic trust funds, hotels management, and the curation of a delightfully miscellaneous Twitter feed.

As Frankopan himself freely admits, his is a packed schedule where he often juggles with more responsibilities and tasks than he has time for. Between an address to the Armenian parliament and chairing fellowship committees at Worcester College, he still manages to make time to respond to my questions.

Elsewhere, his family’s heritage is well-documented, but his personal background and, in particular, his Cambridge years are less well-known, so I am interested in understanding more about his undergraduate time spent at Jesus College. I ask him to elaborate on his connection to Cambridge and, in return, he offers up fond memories:

“Some people refer to their undergraduate years as a golden time when they talk about it later in life. I knew it was a golden time when I was there. Like everyone who gets a place, I felt very fortunate to study at Cambridge; and, like most people, had to juggle with the worry that I wasn’t clever enough with finding the self-confidence needed to negotiate everything from supervisions to heading to gigs at the Junction. But I kept working, turning up to try new things and enjoying my time as much as I could. I got lucky too. Above all, I fell in love with my college sweetheart, Jessica, who was at the same college as me (Jesus): we used to have endless cups of coffee at Clown’s in King Street and to dance in the cellars at King’s which was a thing in those days. But I also loved my history course; I loved being a choral scholar (most of the time); I loved the different sports I played for college and the university; and I loved making lots of friends. So, I glow when thinking about my time as an undergraduate.”

And what is your connection to the university nowadays?

“These days, I’m involved with a few things at the university, from helping interview candidates for research fellowships to supporting the university and my college, sometimes with advice, sometimes helping make connections and sometimes through providing financial support. I’m really proud of Cambridge and still feel lucky and relieved to have studied there.”

Frankopan, now considered a global historian, began his academic career as a Byzantine specialist. His first publication charted the history of the First Crusade from the perspective of Byzantium. I want to hear more about how specialising in the Byzantine period, which is not only chronologically expansive but also relatively understudied, prepared him for making the leap to tackling history on a global scale. As he explains, the progression was not as unconnected as it may outwardly appear. Frankopan begins by addressing the broader implications of this question:

“I am interested in the histories of exchange – and there are no limits to where that can take you. One problem all historians face is that of periodisation and the challenges of defining eras as somehow being distinct. What, for example, are ‘the middle ages’; in what meaningful ways were they different to other ‘ages’; and for whom are they ‘middle ages’ anyway – do these Eurocentric terms have any value when thinking about the history of other continents, peoples and cultures? In the same way, we can get stuck within narrow geographical tramlines: if one starts working on 20th century British history, for example, it can be a leap to then think about the same period in, say, South East Asia.”

He then continues with reference to his undergraduate degree, which specialised in Byzantine history:

“One of the great things about Byzantine history is its profound geographic and temporal breadth: even as an undergraduate, the paper I took on Byzantium included sources relating to Scandinavia and Iceland; to North Africa; to the Gulf; to Central Asia and to China. Plus, Byzantine historians usually grapple with some or all a thousand-year period from c300-1453. So, in that sense, Byzantium provides a great jump-off to explore other peoples, regions, themes and topics. And when one starts to tear down artificial geographic and temporal walls, then other things flow too: like thinking about disease, climate, migrations and big subjects that are in many cases not just continental and inter-continental, but global too.”

Frankopan’s response offers a taste of the dexterous way in which he often weaves together his histories. Frankopan is perhaps best known for his 2015 publication The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. The work bears an ambitious title, but deservedly so – it is a masterful survey of a vast slab of Eurasian history which has rarely been given the spotlight. The book was reviewed to great acclaim, but its strength is perhaps best reflected by the fact that leaders from across Central Asia cite it as a must-read and it can be found sitting on the desks of former Afghan presidents and senior Iranian politicians. In light of The Silk Roads, I ask him what he thought the current pandemic might mean for globalisation.

“Our short-term memories can play tricks on us. Globalisation was under considerable pressure before anyone had heard of Covid-19. The Trump administration has made collapsing global supply chains and re-shoring production and jobs to the US its policy signature, alongside tariffs to level the playing field with China. Brexit too was in part a reaction to hyper-globalisation. It is easy to forget that only 18 months ago Theresa May said, ‘if you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere.”

Could this pandemic put an end globalisation altogether?

“Rising geopolitical tensions, casual racism, quixotic or authoritarian regimes with vast military budgets and add a pandemic – you’re looking at some state-of-existence changing global problems to deal with in the coming years.”

More recently Frankopan has published a follow-up book, The New Silk Roads: The Present and Future of the World, which adds a supplementary commentary to his previous instalment which considers more recent global developments. I ask which of these global trends Covid-19 may have accelerated. Frankopan’s response highlights his appreciation of the serious risks faced by states in the face of this virus. Nevertheless, as in the Union debate, his optimism and belief in the innate compassion and adaptability of the human species shines through.

"Our short-term memories can play tricks on us. Globalisation was under considerable pressure before anyone had heard of Covid-19."

“Accelerated global trends? Take your pick. But by far the most serious threat is that of economic depression on an astonishing scale. It is now a race against the clock to see if we can deal with the worst of that in time, or if the financial pressures prove overwhelming in individual states or, indeed, across continents. We are a remarkably resilient species, though, so while I am fearful in the short term, I am a long-term optimist.”

I follow up this question by asking what the epidemic might mean for the realignment of power across the Eurasian axis. Does it empower or enfeeble China?

“It does both. China’s handling of the first stages of the outbreak was not just chaotic but reckless. That, of course, degraded the credibility of the competence of its bureaucracy. It will be interesting to see what lessons are learned; historically, authoritarian states are not very good at facing reality, especially when it comes to failures, and they invest more time and resource in denial rather than introducing the sort of reforms that would prevent the same thing happening again.”

"We are a remarkably resilient species, though, so while I am fearful in the short term, I am a long-term optimist."

In his work, Frankopan frequently highlights China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’, often seen by external observers as a new Silk Road, or more insidiously, a new type of colonialism. He continues with this in mind:

“Internationally, China is clearly trying to take advantage of chaos elsewhere to make friends through medical and financial support. But in the long run, partnerships, friendships and alliances rely on mutually over-lapping interests and, for now, many across Eurasia, Africa and elsewhere are not clear what Beijing’s aims are.”

Frankopan’s magisterial ability to comment authoritatively on such a vast range of topics has brought him great success. But he has mixed feelings about the temptation to migrate into the spotlight of pop academia. I enquire after his upcoming projects, including the forthcoming Leviathan, which will treat Russian history on the macroscale. Through his response, it becomes clear that he prefers to preserve the part of his life that is dedicated to academia for the library rather than spending time on the television screen.

“I do have a Russian history book that I am keen to write but need to spend 12 months in Moscow at some point. As it happens, I can’t do that right now because of travel restrictions, so I have pushed it back a year or two. Instead, I’m working on another big global history project at the moment.”

What is this new global history project going to look like?

“I’ve been gathering lots of different strands together for a few years about parts of the world that didn’t fit into Silk Roads and slowly thinking about how to tie them all up into a whole. I am happiest just gathering material like balls of wool and I’m not too worried about what they will turn into. But I’ve got enough to now be thinking about a methodology of how to get them into something interesting.”

Frankopan has touched on the challenges faced by a researcher during an era when entering an archive is prohibited. Before our interview comes to end, I ask him to elaborate on the ways in which the pandemic has changed his academic lifestyle and how it might influence our practice of historiography.

“Not all areas of history are the same and, due to my work, I really need access to libraries. But in Oxford, like elsewhere, libraries have been closed for weeks. It’s true that many materials have been digitised in recent years but, as it happens, many of the regions that I’m most interested in are behind the curve because they don’t have the resources, the interest, or the numbers of students and scholars working on them to have been made available online. So not being able to get into the library is a real challenge from a research point of view.”

How are you finding working remotely, away from friends and colleagues?

“It’s also not ideal to be marooned and even though I’m doing a weekly Zoom with doctoral students, I am missing my colleagues, students and friends and not being able to have cups of coffee to talk about the meaning of life. In practice, that makes me think that I’m neither being very productive or original at the moment; but with what’s coming towards us, I don’t think that really matters.”

With that the interview comes to an end. We have covered ground at a breakneck pace and my lasting impression is that Frankopan’s passion for history and his omnivorous approach to research is not just exciting but inspiring – he is a man zooming along the helter-skelter of life.

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026

News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026 News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026

News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026