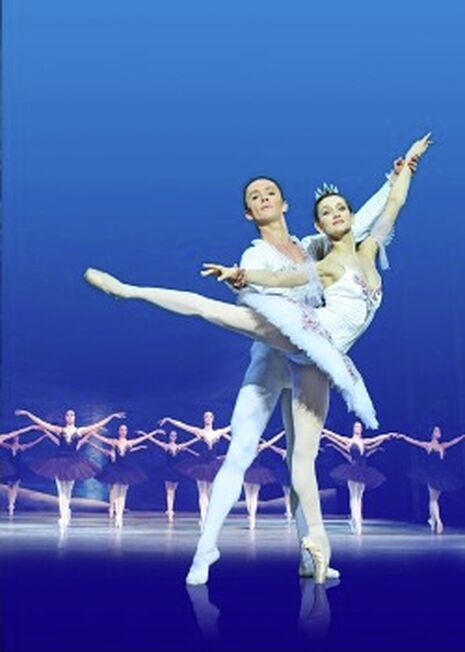

Dance: Romeo and Juliet

The Russian State Ballet of Siberia’s rendition of Romeo and Juliet cast a spotlight upon the chasm between top-class ballet and the half-baked technical and theatrical standards of the companies which are touring every UK city but the capital.

Evoking Renaissance Verona with its family feuds, passionate encounters and tragic twists, Russia’s supposedly acclaimed ballet company began their three-night stint at The Cambridge Corn Exchange, with performances of Swan Lake and The Nutcracker to follow. The audience was lukewarm, and the venue unsuitable for classical ballet. With half of the seating at ground-level, for many the dancers’ feet were out of view and the corps de ballet’s formation rendered indistinguishable.

Not that it was much clearer for those of us in the higher tiers. Unable to maintain the spatial composition of full company numbers, the corps was out of time and, quite simply, messy. Given the limited space for a seventeen-strong cast, the dancers were forced to under-perform movement, which, alongside their extravagant costumes, distracted from the principles of the piece. Christina Fyodorova’s lavish designs ensured that the show was not all tutus and tights, although the cleaner lines of traditional ballet garb would have worked wonders for tightening up the spectacle.

Unsurprisingly, however, the world’s greatest love story lent itself perfectly to breathtakingly beautiful duets. High, sculpted, feather-light lifts flowed into endless pirouettes with tapered elegance in the principles’ portrayal of young awakening passion. We could have asked little more of Ekaterina Bulgutova as Juliet, whose fine-boned physique effortlessly defied gravity and emulated sweetness. Ivan Karnaukhov as Romeo, although spritely, was a little shaky, and upstaged by Vyacheslav Kapustin and Kirill Litvinenko’s solo performances as Mercutio and Tybalt. Their strength, agility and riveting energy was unrivalled, exhibiting movement range which spanned the spectrum of this familiar but shape-shifting art.

The second act was infinitely better than the first. Rather than overpowering the narrative with the packed action of corps pieces (which were, frankly, quite sloppy), death was heralded by haunting solos and absorbing duets, performed with impeccable skill to Tchaikovsky’s score. This musical challenge unfortunately proved too much for the orchestra who, under Anatoliy Chepurmoy’s baton, fell flat.

The excellence of Romeo and Juliet’s principle ballerinas and soloists drew attention away from the pit and the visible errors of the corps, in fact making it a real pleasure to watch. Usually, a good production survives a poor cast; with The Russian State Ballet of Siberia’s performance, quite the opposite was true.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / News in Brief: carols, card games, and canine calamities28 December 2025

News / News in Brief: carols, card games, and canine calamities28 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025