Portraying the refugee crisis in modern cinema

Film&TV columnist Abigail Reeves discusses the ways in which this ongoing political emergency is being absorbed into our cultural consciousness, in her review of Ben Sharrock’s new film ‘Limbo’ (2020)

Limbo: an uncertain period of awaiting a decision or resolution; an intermediate state or condition.

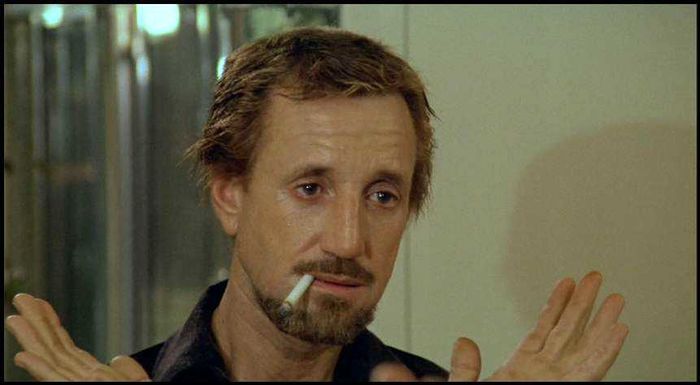

The 2020 film, endowed with this curious, one-word title, tells the story of a group of all-male refugees who have been sidelined in the Scottish Isles and are stuck in such a limbo-like state, waiting to hear news on their sanctuary application. It is director Ben Sharrock’s second feature film and the filmmaker’s experience is made evident through his use of heavily stylised shots to convey his characters’ bare-bones lifestyle, while simultaneously delivering the resonant political commentary of the film.

Throughout the story, we mainly follow Omar, a Syrian musician who carries his grandfather’s oud with him everywhere he goes – his only remnant of home. He lives with Farhad, his mellow companion who endlessly picks up new trinkets from the local donation box, as well as two brothers, Wasef and Abedi. They are left with no hope but to each day wait for the mailman who stops at every house but theirs, withholding the long-anticipated letter of acceptance to release them from this modern-day purgatory.

“Sharrock seems to be asking his audience: as a refugee, how do you fight?”

Sharrock’s direction is confident yet controlled, creating a consistent aesthetic throughout the film, which somehow manages to make ugly 80s sweaters (of which there is an abundance) seem cool. The beauty of every scene combined with its deadpan humour makes Limbo an entertaining watch at the bare minimum. What truly elevates the film, however, is it’s pertinence to today’s refugee crisis and its huge amount of heart when dealing with this topic. The film clearly seeks to enforce the humanity of its subjects. The characters are not merely part of a statistic, portrayed as parasitic thieves, or trapped cattle being herded from one place to another. They are not defined by their status as refugees, but are portrayed as flesh-and-blood humans with hobbies, families, and endless memories of their lives ‘before’.

These refugees have all been abandoned in a seemingly permanent state of waiting, trapped between home and a land of opportunities. They are bombarded by the harsh Scottish weather, shown in all its ever-changing glory through the timeline of the film which stretches over several years, and portrayed as a character in its own right. The bitter winds and bleak skies create a backdrop which, although breathtakingly beautiful, aptly reflects the cold shoulder welcome from the Scottish residents who are themselves similarly neglected by the Government. The locals taunt them, recalling the caricatured, racist image of a Middle-Eastern terrorist that haunts Western nightmares. According to them, Omar and his friends are there to take their women, destroy their homes, wreak chaos and pain. This aimless waiting in such an unwelcoming community erodes any remaining spirit after Omar’s treacherous journey to the UK and rather than using violence or military action, the Government seems to be exercising a much more cost-effective tactic: stick them in the middle of nowhere and wait until they give up.

“Refugees should not have to be plastered, dead, across the front of newspapers for us to care”

This battle against the weather is the most tangible struggle in the film as any progress towards gaining asylum seems next to impossible. Sharrock seems to be asking his audience: as a refugee, how do you fight? By constantly rehearsing for job interviews? Watching your friends water themselves down and become more “British”, more palatable? Erasing every trace of your ethnic identity and culture despite still being marked as an ‘outsider’ by everyone?

Limbo’s political commentary, therefore, is incredibly relevant and will no doubt remain so for the foreseeable future. However, with Afghanistan trumping Syria in most recent headlines with regards to urgent calls to accept as many refugees who are fleeing the Taliban’s take-over, it also exposes how different crises come in and out of fashion. It shows how our short attention span grasps onto them, producing a few Instagram posts and social media outrage, only to fade out just as quickly and inconsequentially as it appeared. And what happens then? These refugees become ‘past their sell-by date’ as one migrant comments (Limbo, 2020). They are no longer in fashion, they get stuck in the middle of nowhere, in a constant limbo, forever.

Refugees should not have to be plastered, dead, across the front of newspapers for us to care. And Limbo avoids this sensationalism or the media’s customary harsh demand for instant guilt and empathy. It’s characters are not degraded in order for us to see their struggle. Instead, there is a quiet unravelling of the whys and the hows of their various complex situations and backstories which adds a warmth to the film despite the Island’s overwhelmingly harsh weather.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026