I can’t untangle the messiness of horror from its seductive beauty

In Emily Sandercock‘s column on horror, she reflects on the genre’s disturbing combination of graphic violence, cinematic beauty, and moral confusion

This piece contains spoilers for Us, Get Out, The VVitch, Hereditary, and Midsommar.

Content Note: This article contains detailed discussion of cinematic violence, toxic relationships and cults

Now that summer is coming to an end and Halloween is approaching, with the chill winds and crunching leaves of fall, I’m thinking — more than I usually do — about horror movies. Horror has been my favourite movie genre since I first saw a horror film at a sleepover when I was 12. In retrospect, the plot of that movie was silly. At the time, though, my friends and I had so many thoughts after watching it that we stayed up until the very early hours of the morning theorising. Where had the evil mutants come from? Had the teenage son secretly been infected by them the whole time? Did this all have something to do with the Cold War? Images from that movie, like one shot of a desert in which a barely visible figure creeps in from the distance, remain vivid in my memory.

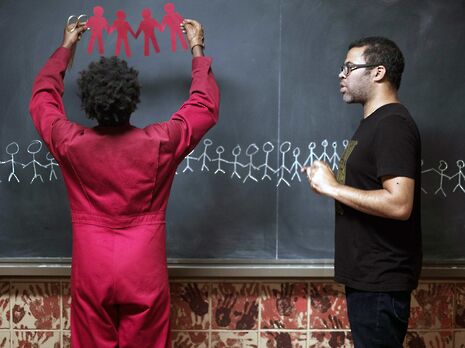

More recently, I have become as obsessed with the movies of Jordan Peele, Ari Aster, and Robert Eggers as I was with the horror movies of my pre-teen years. These directors have formed their own small, sub-genre in the horror sphere. While their movies differ vastly in setting and focus, I am not the first to point out the similarities between them. They have a comparable style, using shots that blend picturesque backgrounds with violent foregrounds. This is present, for instance, in the graphic ritual suicide and murder Aster contrasts in Midsommar with sweeping shots of flower-decked dresses and the idyllic Swedish country side, as well as in the literally balletic, but brutal, fight scene between the protagonist of Peele’s Us and her evil doppelganger. The beauty and the horror of these scenes blends together, and each heightens the other.

The movies are darkly funny, heavily symbolic, and have foreshadowing that seems obvious on a second viewing but is mostly inconspicuous the first time around. In Peele’s Get Out, the black main character’s white girlfriend defends him from a police officer. She seems ‘woke’, but is actually trying to avoid a paper trail, because she is planning, along with her family, to possess and enslave her boyfriend at the end of their vacation. Similarly, in Egger’s The VVitch the main character yells, semi-jokingly, to her younger siblings that she is the witch who lives in the woods. By the end of the movie, she has indeed joined a coven of witches, and runs away with them to the forest.

“Characters gain power and apparent agency. They have also joined murderous cults.”

Explanations for the main events of these movies are left vague. They do not answer the question: ‘why have these bad things happened?’ Get Out, in which the main character kills and successfully escapes from his kidnappers, is the only one with a happy ending. The endings of the others are, to varying degrees, conflicted. On one side of that spectrum is Us, in which the family we have been cheering on defeats the doppelgangers who have been hunting them. However, it is revealed in the last moments that one of them (the mother) is a doppelganger herself, having switched places with her original when they were both children. On the other side is Hereditary, in which the demon that has been plaguing a family throughout the movie successfully kills them and possesses one of them as his host. Midsommar and The VVitch fall somewhere between these. At the end of each their main characters, Dani and Thomasin, respectively, have gained power and apparent agency. They have also each joined murderous cults.

After these movies came out, many people online, particularly on sites like Tumblr, were delighted by these endings, talking about them as empowerment and as fantasy. This attitude is understandable. As these movies mix beauty and gore visually, they also do so in terms of their story, making moments of evil beautiful and therefore seductive. It is beautiful when Thomasin flies into a moonlit sky with the other witches, and when Dani smiles in a flower crown, surrounded by cultists. They have left behind, in Thomasin’s case, a miserable and repressive family life, and in Dani’s a toxic relationship. It is what the audience has wanted for them from the start and masks the fact that they have both become trapped. The good and the bad are intertwined and there are places where it is difficult to tell them apart.

That is where the horror comes from, in the mixture of freedom, evil, and entrapment. I’m still trying to untangle each of those strands — I’m not sure that I ever will.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026