Elton John (Lewis)

Fergus Lamb asks how an advert has taken centre-stage in our holiday festivities

Complaints about the corruption of Christmas are a boorish cliché of the season, as much a tradition as mulled wine, mince pies, and the Queen’s speech. From the right, the accusation is that Christmas has become secularised, its religious content stripped to make it more palatable for the masses. Meanwhile, the left argue that commodification has ruined Christmas, that a celebration of community has become one of commerce. The two critiques are not as different as they originally seem- both maintain that Christmas used to mean more and now means less. However, it’s not liberals, per se, who are responsible for stripping Christmas of its holy content, but neo-liberalism. As that great Santa impersonator, Karl Marx, once said: the logic of capital is such that ‘all that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.’

It is amidst this culture war that, as I walk back to college in the bitter cold, my phone pings- ‘John Lewis debuts new Christmas advert.’ There’s a real absurdity to this: an advert has become such a feature of our holiday season that the thought of it can make me feel so warm inside. As one friend tells me; ‘at least once I year I get in bed and watch all of them in a row and then cry.’ How has this happened? They are often beautifully constructed, a combination of warm visuals, covers of popular songs, and nifty storytelling. It’s probably indicative of our time that some of the best artists alive spend their time crafting adverts for a Highstreet Retail brand. I put the kettle on and settle in.

an advert has become such a feature of our holiday season

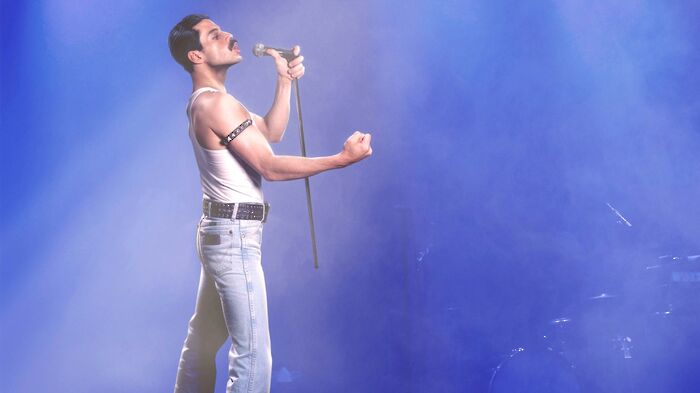

The advert opens on Elton John playing the piano in his big empty house. He’s singing ‘Your Song’, which he wrote, and which has been covered countless times, from Ewan McGregor in Moulin Rouge to Ellie Golding in, well, a John Lewis Christmas advert. As he plays, we’re transported back through time as we see him perform multiple iterations of the song; he plays in stadiums, on planes, sporting a mohawk, in a recording studio, in a town hall. Now he’s a child again, running down the stairs on Christmas morning and his mum and nan are there. He’s tearing the wrapping paper off of his present: it’s… a piano. It’s the same piano he was playing in the opening shot. He begins to play and we’re back in Adult Elton John’s empty mansion. He closes his eyes. ‘Some gifts are more than just a gift’, reads the catchline.

adverts now fulfil the function of traditional media—they’re the medium through which we tell stories about ourselves

Something about the advert feels off –maybe I’ve become older and more jaded (it’s true that Christmas feels less special with every year that goes by.) There’s a darkness to that final shot of Elton alone in his hall that can’t quite be encapsulated by the advert’s sticky sentimentality. He’s like a latter-day version of Orson Welles’ Charles Kane, the piano taking the place of ‘Rosebud’, the sledge that connects Kane with his happier but poorer childhood. When seen through the perspective of this loneliness, the rest of the advert becomes an escape into nostalgia.

The story of John’s fame is played in reverse. As superficial evocations of past eras whiz past, we sense that the fantasy of the film is a search for meaning. This meaning isn’t present in any of those famous people parties or the adulation of his fans, but only in his roots– the sitting room of his grandparents’ council house where he lived whilst his dad served in the RAF and first played the piano. The genius of John Lewis’ advert is to find in Elton John’s story an analogy for a lonely Britain, a Britain besieged by the collapse of community that arrived with late-capitalism, one nostalgic for a post-war consensus when it seemed like that community existed.

Buried within the John Lewis advert, the heart of the British commodification of Christmas, amidst the shots of Elton John’s childhood, there lies an image of hope. An image of what Christmas should and could be about. John Lewis has always understood that people, especially after the financial crash, are sick of the overconsumption of the Christmas period. This is why their adverts rarely feature more than one or two gifts. To an extent, John Lewis is using this cynically to associate their products (which aren’t ‘gifts that are more than just gifts’) with this trend. However, they’re also important because adverts now fulfil the function of traditional media—they’re the medium through which we tell stories about ourselves. Those distraught over the corruption of Christmas should take relief in this development. Within the very core of the commodification of Christmas hides a purer vision: family, love, community, the very things that we seem to have left behind.

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025