Peterloo: Highlighting Cinema’s Troubled Relationship with History

Sam Osborne discusses the challenges and deficiencies of historical representation in film

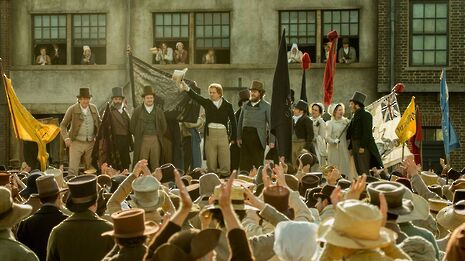

On August 16th 1819, a crowd of some sixty thousand men, women and children gathered on St Peter’s Field in Manchester. The factories of the burgeoning industrial district were left empty that Monday morning, as workers turned out en masse to witness the celebrated Henry “Orator” Hunt make his address. His subject? The extension of representation to the new industrial hubs and of suffrage to all men. Families travelled for miles from the surrounding towns and villages, dressed in their Sunday best to cut a respectable aspect. They were unarmed.

Two centuries on, Manchester-born director Mike Leigh’s new film Peterloo marks the events leading up to and including Hunt’s address, which culminated in a cavalry charge upon the tightly-packed crowd that left at least fifteen dead and countless injured. The events of Peterloo are without doubt worthy of cinematic treatment, yet Leigh’s film is not an easy watch. Its flaws, and indeed, its redeeming features, draw attention to recurring problems faced by filmmakers who look to authentically represent the past while simultaneously being dramatic. It is also an illustration of the perils wrought in attempting to recruit history in favour of a political message.

The film dedicated to the re-enactment of wordy speeches is at odds with a more intimate depiction of working family life

Despite its worthy source material, Peterloo tells its story in a way that is often turgid. The film boasts a high level of historical and political detail, but this is too often curtailed into repetition for the enforcement of the film’s core message. Clumsy exposition abounds, along with scenes of debating reformers discussing the working man and the nature of protest. The most tedious scenes depict Britain’s Regency elites and the Manchester magistrates tirelessly plotting the suppression of the people. Repetition in pursuit of the film’s egalitarian message ironically acts to blunt its emotive impact, as performances grow increasingly hammy and their depictions become near-comical. The focus on the facts leads to an overly-long picture, flouting the key principle of gripping cinema: show, don’t tell.

Studios are always anxious that their productions pass the historical accuracy test. However, the focus on accuracy can come at the cost of narrative depth, and productions of recent years like Lincoln have likewise fallen foul of this problem. Steven Spielberg’s film similarly indulged in endless scenes of detailed debate and rhetoric, and resulted in sleep-inducing sequences which failed to explore the frailties and intricacies of the subject. Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk meanwhile became lost in gritty revisionism, determined to show the horrors of war in relation to a defeat celebrated as part of Britain’s “finest hour”. Its dedication to realism counter-intuitively rendered a storyline with multiple protagonists who speak monosyllabically; we learn little about the characters beyond their names, and are given scant reason to care about them or the film.

Other filmmakers have taken a different approach to represent history, instead actively tweaking historical fact to present emotional truths. Darkest Hour was widely derided courtesy of its infamous depiction of Winston Churchill braving the London underground. The ineffectiveness of this approach has drawn scorn, though not so much for the liberty taken but for the crude fashion in which it is delivered, ramming the message down the audience’s throat.

At the heart of Peterloo is the story of Joseph (David Moorst), a shell-shocked young soldier who returns from Waterloo to unemployment, poverty and hunger. We follow his family, guided by the common-sense matriarch Nellie (Maxine Peake), in the events leading up to the disaster. It is their experiences that imbue the film with any emotional depth. Most striking is the depiction of the massacre itself. The emotional stakes are raised moments before the carnage by a tender moment in which Nellie befriends another family in the crowd, discussing their journey and offering them food. It goes to show the peaceful and sociable nature of the protest far more effectively than any of the previous pontificating of the earnest reformers. The sacrifice of the working people and the injustice they faced in return is emphasised through symbolism far more affecting than the polemicising that dominates much of the film.

Peterloo would be a shorter, more enjoyable and more powerful picture, were it to put greater focus on characters like Joseph and Nellie rather than the polemics of the debating chamber, or the caricatures of the establishment. A strange irony is thus presented, since Leigh has previously made his name with such intimate character led dramas. Watching Peterloo, it is possible to discern two very different films at odds with each other. The film dedicated to the re-enactment of wordy speeches is at odds with a more intimate depiction of working family life, and sadly acts to stifle this more thought-provoking storyline.

The historian Marc Carnes has called on his profession to embrace historical films as ‘jumping-off points’, depictions that, despite inaccuracies, can raise ideas and interpretations of the past that engage a wider audience and can be used to inspire more in-depth historical discussion. Peterloo exemplifies how film can effectively inspire historical dialogues, whilst highlighting the perils provoked by cinema’s attempt to parrot the tone of the lecture theatre. Initial press response to Peterloo was split politically, with those on the left embracing a film they saw as holding a mirror to the contemporary Britain of austerity and rampant inequality. Film is always as much a reflection of its own times as any period it professes to represent, but this overt political message has led other commentators to spurn Peterloo for its less-than-subtle tone. Such overemphasis simply acts to weaken the strength behind any indictment of the present, and could yet negate awareness and discussion of a much-neglected moment in history.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026