Cold War review: a victorious film

Madeleine Pulman-Jones reviews the sensational new Pawlikowski film

Sometime during the first fifteen minutes of Cold War, directed and co-written by Paweł Pawlikowski, a pair of eyes look out at you from behind the screen. The eyes are both human and not human. They are painted onto the wall of a derelict church in the middle of rural Poland, the stone of which has been roughed up to such a degree that the eyes are the only visible features of what was once, probably, the face of Jesus, or at least the Virgin Mary.

Immediately after this shot, Pawlikowski jump cuts to a grazed and gouged dirt road over which a van drives to its next stop on its itinerary of Polish villages. Already the director has made his point: we are stony and vulnerable, the bulldozer and the bulldozed, the cold and the warm (pun intended). But more than that, within this subtle series of perfectly composed shots Pawlikowski has signalled to us that we are more than mere spectators, more than eyes. To me, the secret of his idiosyncratic style of intricate static shots lies not in the compositions themselves, but rather in the gaps in between – in what he trusts us to understand by his omission.

As myself a descendent of misplaced Poles, I feel a strange connection to Pawlikowski’s Poland – as though I were listening to a familiar radio station through thick static. With questions of displacement more important than ever, Cold War, with its nuanced aesthetics of disorientation, strikes a subtly potent chord.

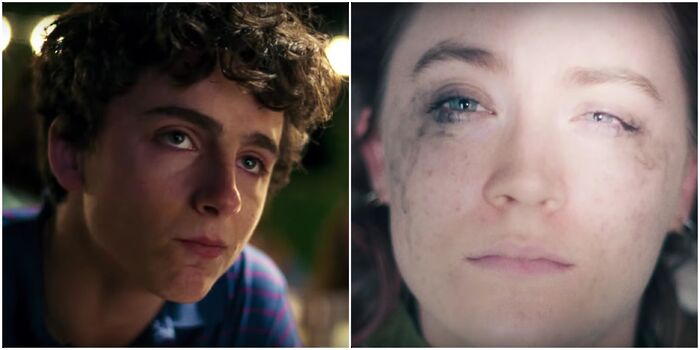

The people in the van are touring the Polish countryside scouting out “peasant talent” for a new troupe of Polish folk singers, designed as a Soviet project to promote Polish culture. A kind of Soviet family Von Trapp, the troupe sets up shop in an empty country estate, where the performers are subjected to a period of rigorous training in traditional folk song and dance. Leading this cultural operation is the stony-eyed Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) the troupe’s pianist, conductor and arranger. Wiktor becomes entranced by Zula (Joanna Kulig), a volatile and vulnerable young woman auditioning who, we quickly learn, was a survivor of sexual abuse and served time in prison for self-defence against her father. The pair begin an impassioned affair which is put to the test when Wiktor declares that he wants to defect to the west while they are touring in East Germany. The second half of the film is essentially the first transposed into a minor key. Though the songs remain more or less the same, they are sung in jazz arrangements or translated into French. Borders are crossed, new languages learnt, new partners found, yet the magnetic force of Wiktor and Zula’s love transcends the constraints of geography, pulling them at once ever closer together, and ever further apart.

Language exists in Cold War as a spatial entity – characters drift in and out of languages as they do in and out of countries

If I were to call Cold War the most stylish film I’ve seen in years I would not be exaggerating. Cold War is, to quote Stingo from Pakula’s Sophie’s Choice (1982), “utterly, fatally glamorous.” Pawlikowski’s Soviet epic, like Sophie’s Choice, cannot escape the tragedy of Polish history, and yet it manages to be contradictorily both obsessed and unconcerned with it. Basing the love story on that of his own parents, “the most interesting dramatic characters I’ve ever come across,” Pawlikowski’s focus never wavers from the emotional meat of their romantic entwinement, giving in neither to the temptation of over-aestheticism nor to an indulgence in Soviet brutality. I find it difficult to imagine a film so bleak and honest, so classy and considered, being produced in America or in Britain (perhaps why Pawlikowski, having spent most of his adult life in the UK, has decided to set up camp in Poland). However, the comparison to Sophie’s Choice is ultimately a superficial one based on a passing resemblance between the protagonists, similarities of plot details, and a shared fascination with amour fou – the film clearly and truly belongs more in the world of Wajda and Kalatozov than in that of Hollywood.

Language exists in Cold War as a spatial entity – characters drift in and out of languages as they do in and out of countries. When Zula moves to France to be with Wiktor, the pressure to translate songs into French becomes almost physically oppressive, expressed in the violent volatility of the pairs’ behaviour and movements. When Zula slips into Russian in her audition song she too is transforming space – the dreary Polish country estate becomes, for a moment, the Russian musical from which she found the song, bringing with it the glamour of cinema, the power of Russia, acquainting us with her own mystery. The choreography of the film’s folk dances struck me as a spatial expression of the rural languages the troupe’s nationalistic leader is attempting to suppress. In an interview for his Oscar-winning 2013 film Ida, Pawlikowski, himself a polyglot, observed that “things look very different from different perspectives, especially if you can understand the local language, logic, the way they see things.”

And so we return to eyes, to looking. Cold War’s Zula depends more on language and on sound, than her silent precursor, Ida. Take sound away from Ida, and it would remain just as affecting. Take sound away from Cold War and it would cease to exist. What Pawlikowski has achieved in Cold War is the elusive marriage of sound and image, a pairing unfortunately far more harmonious than that of its lovers.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026

Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026