Review: Architectural designs for living in Kékszakállú

In the first review from the Cambridge Film Festival, Madeleine Pulman-Jones finds in this Bartók opera-inspired film an empowering tale for women

Lines dominate the visual dialogue of emerging Argentinian auteur Gastón Solnicki’s debut narrative feature, Kékszakállú. At the centre of Solnicki’s immaculately composed shots, a girl processes polystyrene pipes in a factory, another younger one tentatively creeps towards the edge of a blocky white diving board, yet another rotates her notebook over and over again, meticulously drawing line after line for one of her industrial designs.

“Everyday acts become a kind of architectural practice”

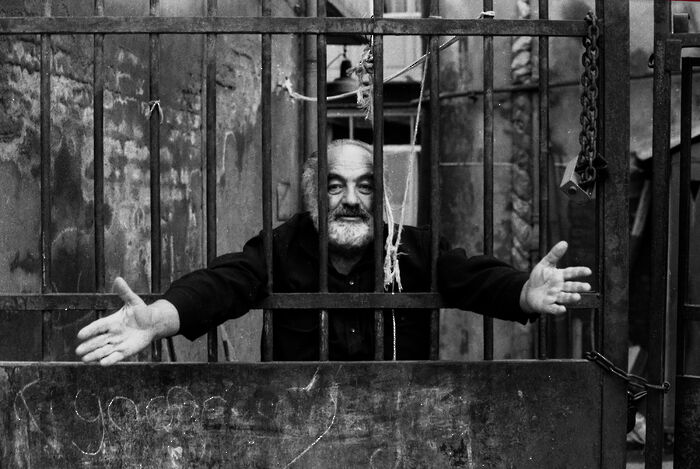

The most striking linear (or perhaps not quite so linear) movement in the film appears during another young girl’s attempt to find her way downstairs to a party at her summerhouse. She walks out onto the balcony dressed in her typical ‘little black dress’ and teetering heels, and struts confidently along a ledge at the side of the house, expecting a staircase at its end. The ledge ends as abruptly as it started, and against the sterile whitewashed walls of the house, the ledge and the girl almost resemble a line in a notebook and the first ‘I’ of a diary entry respectively. This image defines as well as any the essence of Solnicki’s feature – a feature peopled with adolescent women who are about to fall off the cliff of adulthood but who are already building a bridge to the other side.

Kékszakállú (or Bluebeard) takes its title and main source of inspiration from Bartók’s opera Bluebeard’s Castle, a recording of which drifts in and out of the otherwise soundtrack-less film. One would be excused for wondering how this might possibly be true, given the drastic difference in tone and register between the two works.

Bartók’s opera tells the story of Judith’s arrival at Bluebeard’s castle. Judith is intent on opening all the doors in the house to let light in, but Bluebeard asks that she love him unconditionally and leave the doors closed. Finally, she gets her way and, opening the first door, finds that it leads to a torture chamber drenched in blood. Disgusted, she perseveres in opening the doors which lead to yet more unexpected horrors, culminating in the discovery of Bluebeard’s other three wives. By contrast, Solnicki’s film features a group of unnamed adolescent girls all on the brink of adulthood, forced to confront questions such as what degree to study, what job to get, and how to properly boil an octopus.

Solnicki’s predilection for architectural structure is less surprising when one discovers that he based the film on an opera whose main dramatic device is the opening and closing of doors. Nevertheless, his fascination with the practice of drafting things, of making things with one’s bare hands goes far beyond having a character curious about architecture and industrial design. In Solnicki’s film, everyday acts become a kind of architectural practice. An octopus must be dunked three times into a pot of boiling water, inspecting the curvature of its tentacles after each rinse. Standing under a cold swimming pool shower – a visual and sonic explosion defining otherwise empty space. The new relationship to each other that strands of hair take on when splayed out at the surface of a swimming pool.

At 72-minutes, the film is notably short for a festival circuit release. However, a cut any longer might have stretched the avant garde and intimate concepts that make the film so unusual into contrived choices made for the sake of spectacle rather than artistic merit. Artistry aside, the film is notable for its admirable portrayal of young women. The characters in Solnicki’s film (unusually sensitively performed by the youthful cast) eat dinner together, they try on dresses together, they steal extra photocopies of lecture handouts for each other, they work together. Films designed to empower women in an accessible yet slightly didactic way such as Wonder Woman (2017) are important, but what Solnicki achieves, which is perhaps more crucial and far harder to arrive at, is the elevation of the mundanity of women’s day to day lives to poetic importance.

The quotidian experiences of men have been centre stage of art house cinema since time immemorial, but more and more attention is being paid to the understated, woman-centred cinema of Eric Rohmer, Chantal Ackerman and Mia Hansen Løve, among others. Is it time we added Gastón Solnicki’s name to that list?

Kékszakállú is being screened as part of the Cambridge Film Festival at 18:00 on Saturday 21st October at Downing College, and at 10:30 on Sunday 22nd October at the Arts Picturehouse

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026 Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026

Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026 News / Cambridge and Manchester Universities meet for innovation partnership26 February 2026

News / Cambridge and Manchester Universities meet for innovation partnership26 February 2026

![How to Create an Attractive Freelancer Portfolio [5 Tips & Examples]](https://www.varsity.co.uk/images/dyn/ecms/320/180/2026/02/vitaly-gariev-ho2tNOWZYXM-unsplash-scaled.jpg)