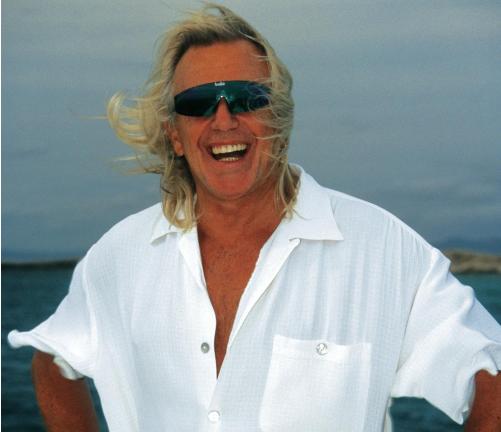

String Theory

, owner of the world-famous Stringfellow’s strip clubs, speaks to and about strippers, professionalism and, above all, philosophy

There is occasionally a counter-intuitive contrast between an artist and his works. Stringfellow’s club is loud, loaded, and louche, yet the man behind the world-famous strip-club is self-aware, sharp, and at times even philosophical.

Stephen Hawking’s books overflow with scientific complexities, yet when the great physicist visited Stringfellow’s, he was not there to indulge in the higher pleasures. Desperate for a discussion, the owner approached his erudite guest: “Would you like to talk about life and the universe, or would you just like to look at the girls?” he asked hopefully. Hawking opted for the girls. And in the words of Peter, “It was one of the saddest moments of my life”.

Stephen Hawking’s books overflow with scientific complexities, yet when the great physicist visited Stringfellow’s, he was not there to indulge in the higher pleasures. Desperate for a discussion, the owner approached his erudite guest: “Would you like to talk about life and the universe, or would you just like to look at the girls?” he asked hopefully. Hawking opted for the girls. And in the words of Peter, “It was one of the saddest moments of my life”.

Peter Stringfellow is a man who embodies contradictions. He is not only a flamboyant playboy, engaged to a 25-year-old beauty, who makes his millions from girls taking their clothes off. He is also a consummate professional, a fierce supporter of higher education, and a self-taught businessman.

The walk up to his office might lead you to think otherwise. Photos of past ‘angels of the month’ – the dancers from his ‘heavenly’ club – line the walls in topless poses. But Stringfellow’s office itself is surprisingly tame: the most prominent items on display are a photograph of his granddaughter, a large portrait of a possible relative - an eighteenth century pastor named William Stringfellow - and a picture of himself in hair rollers.

It soon becomes clear that Peter is rarely passive. He enters and immediately puts us on the spot. “You’re interviewing me on what?” he asks, before continuing, without a pause, “I go in eras and each period is a book and a film”.

We decide to start at the beginning. Stringfellow grew up in Sheffield, and left school at 15 to join the merchant navy. “I had no choice. I had a form of dyslexia, which was totally unrecognised in those days. I couldn’t spell… I still can’t spell ‘entrepreneur’, but I can spell ‘success’: S-E-, sorry, S-U-C-C-E-S-S.” After a brief stint as a salesman - which also landed him a brief stint At Her Majesty’s Pleasure - Peter put on his first club-night in 1962.

He points out a poster on the wall that was the original advertisement for the night: “It looks like it was painted by some kind of mentally retarded nine-year-old,” he laughs, “I was 21 when I painted that.” In the bottom corner of the poster is a crude drawing of a cloud with the number seven inside it. Peter had intended it to allude to Cloud Nine.

Despite humble beginnings, Stringfellow’s career as a music promoter boasts some impressive bookings, particularly considering the venue for his first gigs was a local church hall. The artists he hosted during these early days include The Beatles and Screaming Lord Sutch (best known to us as the former leader of the Monster Raving Looney Party; best known to Peter as “a fucking hard-nosed rocker”).

The conversation then reaches a brief interlude while Peter pauses to take a phone call, nonchalantly discussing the sale of a yacht.

Although a lack of formal education served as no limiting factor on his subsequent success - initially as the promoter of music club nights, and later as a strip club owner - Stringfellow is a firm believer in education, and has spoken at both the Oxford and Cambridge Unions. Which one did he like best? “I prefer speaking in Cambridge”, he says, “but food for food you’re both crap, so don’t worry.”

It is no small task getting the garrulous Stringfellow to move from one topic of conversation to the next, but eventually we coax him onto the subject he is most commonly associated with: strippers and strip clubs.

Stringfellow’s was the first venue in Britain to gain a licence for tableside dancing, though the battle to secure it was long and hard-fought. Peter remembers the censorious male judges, scared by the very concept: “Oh God, naked girls, no – are they Christians?” he parodies. It was a “beautiful female magistrate” who finally gave him the go-ahead. One newspaper advert, two weeks and 360 auditions later, Stringfellow’s opened its doors to the public.

Since then, the club has received criticism from certain quarters. Is stripping something which exploits women? “No”, Peter quickly retorts, “all my girls are self-employed; they want to work here,” an answer he is undoubtedly used to delivering. “Two feminists were even prepared to help me make the case for opening Stringfellow’s”, he continues. And would he be happy for his granddaughter to work as a tableside dancer? “Yes, if that’s what she wants to do”.

If anything, he gives the impression that the women are exploiting the men. They financially appraise the punters - coldly referred to as “customers” - by their watches and shoes. And the pay is good: it is not uncommon for a dancer to make thousands of pounds in one night; the current record stands at £50,000. Nor is the attitude towards women particularly sexist. Stringfellow describes how one of his old managers entered his office after addressing his secretaries as “darling, darling, sweetheart”. Peter’s response was firm: “Shut the door and sit down. These aren’t darlings, sweethearts, babies. They’re Pat, Chrissie, Angela – these are my staff.”

What frustrates Stringfellow is that sex remains “the final taboo”. He cannot understand why a naked woman can advertise shampoo on the side of a taxi, but the head-and-shoulders of a female body is banned when accompanied by an advert for a strip-club. While you can have “a chef going ‘f*ck you, you c*nt’” – part of Peter’s charm is his ability to voice obscenities with phonic asterisks – on television, Stringfellow tells how his idea of a pole-dancing version of X-Factor had the producers running. “Sex frightens people worldwide,” he says.

Peter’s own ethics are economic. He has no moral objection, for instance, to prostitution, even though a girl is fired if she is caught going home with a client from his club. His reason? “It’s not business. Where’s my business in a girl going home?”

The same hard-nosed attitude has got him into trouble. In 1994 he banned fat girls from his club. The story made the front-page of the Sun, but Peter defends his decision. People come to Stringfellow’s to see beautiful people, to bask in the glamour and glitz. Obesity is not good for business. He launches into a one-man role-play: “Unfortunately your fat friend behind you ain’t gonna get in... But she’s wonderful, really lovely… I don’t care.”

It’s all about business, yes. But is it all about money? Certainly not. Although the opportunity has arisen countless times, Peter has always refused to franchise Stringfellow’s as a brand. He refuses to establish Stringfellow’s PLC, and does not want to be a spokesman for his whole industry. Despite his moniker, “King of Clubs”, Peter’s involvement is with his clubs alone, and it is a deeply personal involvement: “Sadly I’m a loner. I enjoy immensely what I do and have done. All the enjoyment has held me back. There’s been a thing in my head about personal ownership – it stops me being a PLC, a Richard Branson. He’s smarter than me. I will delegate jobs, but not responsibility. I keep responsibility.”

An uncompromising rationality defines his philosophy of life. Peter speaks of his contemporary Cliff Richard, whom he admires for releasing the first true British rock song, “but his simplistic view of God - oh God!” he exclaims, “he thinks he’s doing God’s bidding… what? Go to the middle of the Iraq battlefields and see what God’s telling you to do there... I think the future is secular- it has to be. But that’s not to say there aren’t amazing things out there in the universe.”

It is nigh on impossible to give an overall impression of Peter Stringfellow after spending two hours with him. We imagine it would be even harder to do so after more time with him: every minute reveals another facet, another contrast.

He does, however, leave a lasting impression of extreme generosity: that night at Peter’s clubs (he is keen that we see both his London establishments), we are treated to dinner, flowing champagne, and private dances from the club’s glamorous girls – all completely on Peter.

Stringfellow is a natural celebrity, in love with the media only slightly less than he is enamoured with youth; a student journalist’s delight. He might struggle to spell “success”, but his selling-point is pragmatism.

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025