The Price of Victory

The growing industry of political betting gets punters to put their money where their mouth is, and reckons Hilary Clinton is almost a certainty for the 2008 election. looks at the science of wagering on the future.

If you think you know something about politics, you probably think you have a better-than-average idea of who’s going to win the next election. Just how sure are you though? Can you say by how much? Would you put a price on it? An increasing number of people think they can, and are prepared to put their money where their mouth is.

Betting on political events is one of the fastest-growing sectors of the gambling industry. On Betfair.com, the largest internet betting exchange, the outcome of the next general election has attracted half a million pounds of bets, more than the average Premiership football match. If you add bets on other exchanges and wagers on international political events, it’s a multi-million pound industry. Politicalbetting.com, a web site that hosts daily discussion about political events in Britain and abroad from a gambling perspective, is the most visited political commentary blog in the UK.

But there’s far more than money at stake in this new craze. These hundreds of thousands of uncoordinated bets, made by tens of thousands of people who never meet each other, are beginning to change the nature of political prediction. Just as the financial markets aggregate the beliefs of millions of investors to produce a best guess for the future prospects of companies around the world, so journalists, pollsters and politicians themselves are beginning to sit up and take notice of what the betting markets can tell us about what might lie ahead in the world of politics.

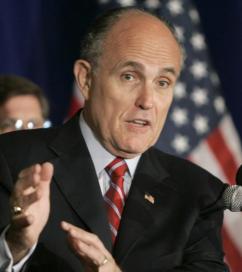

This is not a particularly new idea. For nearly twenty years, the University of Iowa has run a market in predictions about the outcome of US Presidential elections. The rules are fairly simple. Speculators buy or sell “contracts” that specify which party they expect to win the election. Once the election is over, contracts specifying a Democratic win are worth one dollar if the Democratic candidate has won and nothing if the Republican candidate triumphed. So, if a Democratic win seems highly likely, the contract will trade at a price very close to $1. If the Republican seems a shoo-in, you’ll be able to buy a Democratic contract very cheaply. As there is real money at stake – up to $500 per participant – the market moves quickly to adjust to relevant news. If Hillary Clinton makes a gaffe or Rudy Giuliani gets George Bush’s endorsement, the market prices will change rapidly to incorporate this new information. In theory, the price of each contract represents the chance of its specified party’s victory. What’s more, it seems to work in practice. In each of the last five US Presidential elections, the Iowa market has predicted the outcome more accurately than either the average of the final week’s opinion polls and the judgement of political pundits.

It’s only in the last few years, however, that prediction markets have gone mainstream. The Iowa market is small, restricted and narrowly defined. With the advent of internet betting exchanges, the scope for creating wider and bigger markets has ballooned. Punters have always been able to back political parties at the local Ladbrokes, but sites such as Betfair and Intrade have changed the nature of the game completely. At these exchanges, there is no bookmaker: you are betting against your fellow participants. So for every person who believes that the Tories will win the next election, there is another who thinks he can make money by taking the opposite position. Consequently, Betfair and its competitors act like free markets in information. If I want the best estimate of Hillary’s chances of becoming President, I can simply direct my browser to Betfair and see what the punters think (The answer, incidentally, is around 52%. If you think this seems way off, well, there’s money to be made).

Of course, information markets are not an alternative to traditional opinion polls, since polling is still one of the most important influences on prediction market prices. However, these markets do help political actors understand how seriously to take a given poll. Is that new 10% lead an anomaly or the sign of a sharp change in public opinion? Research suggest the prediction markets are the best way we have of making a judgement. How much do polls conducted two years before an election matter? Again, the prediction markets provide a good estimate.

In fact, such markets have proved so accurate in the world of party politics, that there have been several attempts to harness their power in other fields. Markets have been created to estimate future Hollywood blockbuster profits and the success of new products within high-tech companies. It’s still early days, but so far the results are promising. However, prediction markets have also suffered serious setbacks. Perhaps the most ambitious experiment of all was the Pentagon’s attempt in 2003 to create a Policy Analysis Market, which would have allowed members of the public to speculate on the likelihood of future terrorist attacks, coups d’état and assassination attempts. The idea that people – and even terrorists themselves – might be able to benefit financially from loss of life met with outrage, and the Pentagon withdrew funding from the project before it launched. Nevertheless, enthusiasm for greater use of prediction markets in public policy is far from over. Several American academics, notably the economists Robin Hanson, of George Mason University, and Justin Wolfers, of the Wharton Business School, are working on how such markets might be used to evaluate the expected outcomes of government policy decisions. The idea has even made its way onto the bestseller lists in the shape of James Surowiecki’s 2004 book, The Wisdom of Crowds, and has been mooted as a means of measuring the success of the American troop surge in Iraq.

In fact, such markets have proved so accurate in the world of party politics, that there have been several attempts to harness their power in other fields. Markets have been created to estimate future Hollywood blockbuster profits and the success of new products within high-tech companies. It’s still early days, but so far the results are promising. However, prediction markets have also suffered serious setbacks. Perhaps the most ambitious experiment of all was the Pentagon’s attempt in 2003 to create a Policy Analysis Market, which would have allowed members of the public to speculate on the likelihood of future terrorist attacks, coups d’état and assassination attempts. The idea that people – and even terrorists themselves – might be able to benefit financially from loss of life met with outrage, and the Pentagon withdrew funding from the project before it launched. Nevertheless, enthusiasm for greater use of prediction markets in public policy is far from over. Several American academics, notably the economists Robin Hanson, of George Mason University, and Justin Wolfers, of the Wharton Business School, are working on how such markets might be used to evaluate the expected outcomes of government policy decisions. The idea has even made its way onto the bestseller lists in the shape of James Surowiecki’s 2004 book, The Wisdom of Crowds, and has been mooted as a means of measuring the success of the American troop surge in Iraq.

It is a little premature, however, to declare information markets a panacea. Politicians may be able to spin away the results of an opinion poll or to summon minions to rebut the pundits, but some believe that political parties have much more insidious ways to deal with adverse prediction market prices. As the Liberal Democrats prepare for a second leadership election in two years, there has been considerable discussion on the blogs of political aficionados about anomalies in the betting prices last time around. Ming Campbell and Chris Huhne seemed the only plausible winners, and private polling put Campbell well ahead of his younger rival among Lib Dem members. Nevertheless, Huhne was backed with sufficiently large sums of money that he was quoted as the favourite on the major exchanges until just before the result was announced. It would be one thing for the markets to have “made a mistake”, but Mike Smithson, the owner of Politicalbetting.com and perhaps the most influential person in the British political betting community, has another explanation. He suggests that supporters of Chris Huhne, aware of the value of appearing the favourite, manipulated the relatively illiquid market by placing large bets in favour of their candidate.

As Campbell was ultimately victorious, it is easy to dismiss such activity as rather self- absorbed silliness on the part of a small group of political junkies. But in a world where prediction markets are given increasing weight, and in which their prices are widely reported in the mainstream press, it is perhaps a worrying sign of things to come. Unlike many of their financial counterparts, most prediction markets are very illiquid. Few people, for example, know or care enough to invest much in a market dedicated to predicting the identity of the next Russian president. It therefore takes a fairly small amount of money to make a no-hoper look like a certainty or to transform the favourite into a deadbeat. Rumours abound, for example, that Hillary’s current price is the result of concerted manipulation. This, however, seems unlikely. The US Presidential election market is the largest political prediction market in the world. It would take several hundred thousand dollars to make anyone appear significantly more popular than he or she really is – money that the candidate would surely rather put to other uses and that would be eagerly snapped up by punters who spotted the ruse. It is a testament, nevertheless, to the growing influence of prediction markets that such speculation surfaces and is deemed worthy of comment.

As the next US Presidential election draws closer, it’s likely that political prediction markets will be the subject of ever greater public attention – and public scrutiny. They represent neither a catch-all solution to the problems of polling nor an infallible guide to future events; but, they do produce information that otherwise would simply not exist. In a world where campaigns cost hundreds of millions and every technological advance is soon applied to the art of getting elected, it’s information that journalists, academics and the candidates themselves will find it difficult to ignore. Right now, the market says Clinton vs. Giuliani, Clinton to win. Care to bet against it?

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026