Interview: Dan Jones

Helen Charman talks to historian and journalist Dan Jones about his new book, Cambridge and Horrible Histories

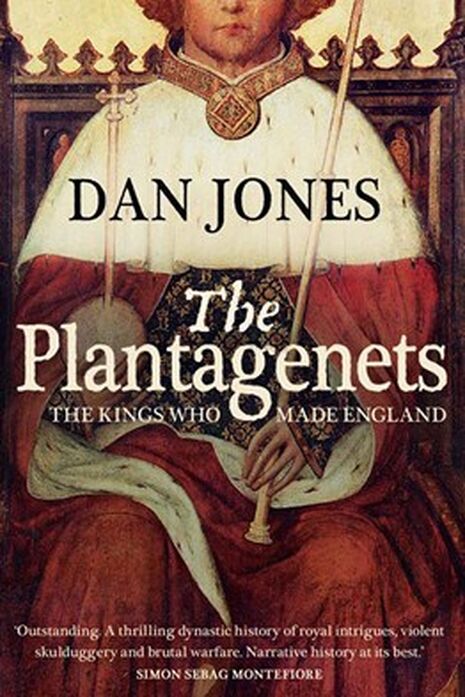

I meet Dan Jones in Melanzana, his “local Italian” in Battersea Square, and I am immediately struck by the slightly unsettling realisation that he is not that much older than I am. Only a decade after graduating from Pembroke with a first in History, Jones has the kind of career that most current finalists would trade several St John's May Ball tickets for. The historian, columnist and magazine editor has just published his second book, The Plantagenets: the Kings who Made England, which has won favourable reviews for its energetic discussion of some of history’s most interesting characters and its accessible approach to scholarship.

Jones admits that he enjoyed the writing process more for The Plantagenets than for his first book, Summer of Blood, and he talks engagingly about how looking at a long period of time (the book covers over a century) benefits our understanding of the behaviour of individual rulers: “ideas about kingship, the nature of rule, the nature of law, the nature of justice; all of these evolved over centuries, and I thought it would be interesting to chart that process”.

He also emphasises the fact that despite their sheer remoteness, the 13thand 14thcenturies contain a huge amount of relevance to today’s society, observing, for example, that we are still seeing the consequences of Edward I’s assertion of English power over Scotland today: the upcoming 2014 referendum on Scottish independence illustrates that the repercussions of this humiliation of the Scots is still being felt today, over seven centuries later.

Validity and relevance, however, are in fact not he believes what History should be about: he is vehement in his denouncement of the idea, still current during even his time at Cambridge, that “biography should be left to women” as “bullshit, quite frankly”. Jones is entirely convincing in his assertion that “History is at its core a popular discipline”, and that “If you want to engage people in writing about history, it is vital to write about people. This is a human world we live in”.

This notion of human interest is intrinsically linked to the stories present at the centre of History, something The Plantagenets very much focusses on, and Jones credits these with sparking his interest in his subject- alongside an incredible History teacher. I ask him whether he takes any side in the current battle going on about the National Curriculum, particularly in the way History is taught, but he maintains that “what’s more important than the subject matter of the curriculum is, and always has been, good teaching… if you ask anyone what got them first interested in their subject, any subject, it’s almost always a brilliant teacher”. He sings the praises of the CBBC show Horrible Histories in its ability to get children interested in his subject, saying with a grin that he is “only being half facetious when I say that Horrible Histories is the best thing that has happened to History for twenty years”.

In the Preface to The Plantagenets Jones states that the book is written “primarily to entertain”, and he is certainly part of what could be seen as a rising wave of intelligent entertainment, perhaps the most recent example being Mary Beard’s acclaimed BBC series Meet the Romans. Jones agrees that we now have some “brilliant communicators” in the academic field, listing Beard, David Starkey and Helen Castor as notable examples, although he acknowledges that not all academics should be trying to be reach a popular audience, and vice versa: “there is always going to be that division; the best people bridge it”.

Speaking of Starkey, Jones was taught by the controversial historian whilst at Cambridge, and describes him as “wonderful. He was generous with his time and his ideas and, most importantly, he taught me how to write”. The obvious fondness with which Jones speaks of his time at Cambridge is so touching it makes me almost pre-emptively nostalgic for my own, although he admits that though he “would have loved more time at Cambridge, I don’t have the temperament for a career as an academic”. Of his time as an undergraduate at Pembroke (he graduated in 2002) he says the most valuable things were “the freedom of being able to live on your own terms, and being surrounded by creative, interesting, fun people”, although the nightlife was, as ever, a mixed blessing: “whenever my foot sticks on a carpet, I think of Cindies”.

When I ask him what advice he has for students facing the undesirable prospect of graduating in a recession, he is vocal in his outrage at the financial situation forced upon today's undergraduates. “I would be terrified if I were a student now”, he admits, going on to say that “I have no idea how we can be in this situation where we are sending students to university and saddling them with obscene amounts of debt”. He denounces the move towards placing a “monetary value on education” that the fee rises have contributed to, particularly in its risk of putting students off studying purely academic subjects: “It’s an absurd and specious link. Can anyone in government honestly believe that? The idea that the importance of going to university is to make yourself employable is beyond tedious”. The advice he would give to current students, then, is prosaic to say the least: “Fuck it! Just make the most of your time, and don’t think about it- plenty of time for worrying later”. Going to university- particularly one as intense and unique as Cambridge- is your only chance to enjoy studying for its own sake, and to make the most of the freedom that comes with student life.

I leave the restaurant with excellent directions to Clapham Junction, a copy of The Plantagenets and an overwhelming sense that if we manage to be half as sorted as Dan Jones ten years after graduating, we'll all be doing fine.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026