It’s a scandal on the dancefloor…

From gatecrashers to window-smashers, Ella Hawes recaps Cambridge’s May Ball scandals through the decades

For as long as there have been students walking the streets of Cambridge, there have been students behaving badly. At no point in the year is this more true than in the hallowed, glorious time of May Week, when the agony of exams is over and a seven-day bender concludes the academic year. But what about when there is just a little too much fun, when poor choices lead to carnage, and overeager committees get a little too edgy?

Step back in time with me to the 1920s. A May Ball ticket sets you back £2 or less (roughly £30 in today’s money when adjusted for inflation). The best bands travel down from the London clubs to perform all night for couples lining up in the ballrooms. Champagne flows freely, not a lukewarm can of Stella in sight.

Then in 1931, Trinity made the unprecedented step of outlawing gatecrashing, putting a stop to the long long-standing tradition of free movement between balls in the early hours; a ball crawl, if you will. But with the ending of one tradition, another was born. Gate crashing has now become a ubiquitous feature of May Week, with Varsity even publishing a how-to guide for the prospective crasher all the way back in 1965. The article’s advice included: bringing a corkscrew and a cigarette lighter to ingratiate yourself with other guests, along with wire-cutters and a lock pick, and not wearing clothing that might impede a swift escape.

It appeared that a certain student back in 1992 took this advice to heart, rocking up uninvited to a Pembroke May Week event “naked except for a pair of boots.” Astoundingly, they let him in anyway, because they “didn’t think he should stand around in the street” in his current state. This inspired several other gatecrashers to try out his unique method, stripping off in the hope of gaining entry. When their nudity failed to gain admittance, the situation devolved into violence, and finally the police were called.

Countless brawls and scraps, fights and quarrels have occurred over the decades, with students often winding up in Addenbrooke’s when alcohol (and testosterone) levels start running too high. There was a simpler time when these matters were handled with a touch more class, as in 1932, when a disagreement fuelled by exam stress led not to a punch-up but a duel, with rapiers drawn at dawn on the Girton grounds. Luckily, the police intervened before satisfaction was had.

“The police are perhaps the most common gatecrashers of all”

In fact, the police are perhaps the most common gatecrashers of all, inevitably winding up at a ball or two during May Week. In the eighties, Jesus May Ball had its licence revoked for a year following the performance of Gary Glitter. Thankfully, his only crime that night was noise disturbance, waking up residents three miles away and leading to much tighter noise control.

The rise of famous faces appearing at the balls began in the seventies and eighties, as many balls hoped to rectify poor ticket sales and frequent cancellations of events. This was partly caused by the overwhelmingly male student population, with colleges struggling to hype up boys to attend events without the hope of snaring a date. Women found the opposite issue a few decades before, as instead of being inundated with invites, they were forced to leave the city altogether. Unless the young bluestockings had family members in Cambridge to chaperone them to the balls or had “made very special friendships during the year” as one 1931 article put it, they were expected to leave the city before the start of May Week and were not allowed to join in the fun at all.

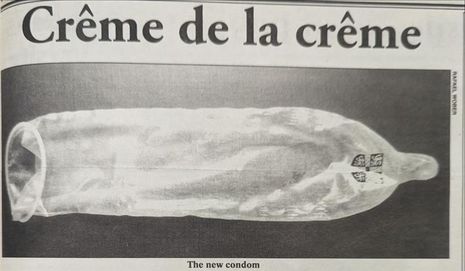

By the nineties, the balls were largely in the iteration we know and love today. Women roamed the streets unchaperoned (at last!), while semi-naked men were an element of set dressing at several balls. In 1994, the University even took the precaution of producing branded condoms to hand out for May Week, coming in three different colours with a dainty University crest at the tip, with the Varsity offices handing them out on a ‘first come, first served basis’, no pun intended.

“In 1994, the University even took the precaution of producing branded condoms to hand out for May Week”

In this decade, themes also became a prevalent feature of most colleges’ May Balls, but with this excitement came a whole new category of foolishness from committees. In recent years, we’ve seen the overtly racist and offensive (The British Empire, Emma, 2009; The Beautiful South, Eddies, 2014) to the unfortunately timed (Pembroke’s Underwater theme coinciding with the drowning of an alumnus, 2023).

The most recent scandal of this ilk was Churchill’s curious theme choice of Aftermath for this year’s ball, featuring a launch party decked out in festive warzone chic, despite sensitivities relating to the current political climate. Shockingly, this is by no means the first time that the management of a Ball has made this misjudgement. Back in 1990, Catz chose the theme of ‘The Blitz’, until a massive outcry led to the theme being overturned. The President of the event claimed it was “very strange” that people were offended, as although “people died […] you’ve got to show the good side of these things.”

Perhaps the most unsettling use of war as a form of entertainment was during 1939. Snuggled alongside articles about compulsory conscription for Oxbridge boys and flight training in Cambridgeshire, Varsity chose to run an advertisement for champagne, which boasted a wonderful price due to the catastrophic state of the French economy.

“As long as there are balls to attend and free booze to drink, there will be students making silly choices, and having far too much fun.”

Even though the Balls were suspended during the world war, this did not prevent students from finding other ways to celebrate post-exams. In 1940, one student got a little carried away and “smashed a couple of frosted glass windows with his hands” and wound up in hospital. Instead of a Dean-ing or a caution from the police, the boy’s father “decided that he shall enlist voluntarily and leave the University.” The stakes were considerably lower in 1962 when a remarkably similar incident saw a student and his friend somersault through a window while pub crawling to celebrate the end of exams. But it really wasn’t as bad as it sounds; if you don’t count the 36 stitches in Addies, the student made it out relatively unscathed, telling Varsity, “the next thing I can remember was being in the Criterion having another pint.”

Some students took their May Week vandalism in a more creative direction. Allegedly, one John’s student back in 1952 decided to turn his bedroom into “a sumptuous garden—painting the ceiling blue and carpeting the floor with real turf which was duly watered every day.” A week later, the weight of the bedroom jungle and its daily watering became too much, and the room collapsed into the floor below.

Although the tradition of end-of-year pranks has largely slipped into the mists of time, I think it’s quite clear that we haven’t really grown up very much in the last century. It’s fair to say that as long as there are balls to attend and free booze to drink, there will be students making silly choices, and having far too much fun.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025