Acting and sleepless nights: King Charles’ time at Cambridge

Sophie Macdonald takes a look through the Varsity archives, revealing the King’s first impressions of Trinity

You’re not seeing double – during his student days at Cambridge, King Charles III had a look-alike. Philip Heslop was commonly mistaken for the King, so much so that, in an interview for Varsity in 1968, he confesses to “tr[ying] to look regal” after people nudged each other and pointed at him during a concert. Despite trying, he “couldn’t keep a straight face and after a while people realised” — mimicking the King’s decorum was evidently the hardest part.

Clearly, faking the crown must be a common trait for Union presidents to adopt. Heslop was the president of the Cambridge Union and chairman of the Cambridge University Conservative Association. But, unlike Bradwell in 2020, he didn’t have an article in The Times to show for it.

In his interview, Heslop also states that “the most dramatic incident” that occurred as a result of being mistaken for the King “was when some youths came up to me in the middle of the night. ‘There’s Charles,’ they said. I thought they were going to attack me.”

Heslop tells Varsity that “people come up to him in cinemas [and say] ’I’ve seen you before’”. The resemblance must have been uncanny: Heslop admits that he “do[es] wear [his] hair the same way as the Prince.” He also claimed to have a “better understanding of the Prince’s problems now”.

While King Charles read Anthropology, Archaeology and History at Trinity College, Philip Heslop read law at Christ’s College from 1967 to 1970. After graduation, Heslop also became one of the youngest and most respected QCs of modern times.

He acted successfully for Alan Sugar in his dispute with Terry Venables regarding Tottenham Hotspur, Ken Bates for the attempted takeover of Chelsea FC and Richard Branson against T-Mobile concerning the sale of G3 telephone licences. He was even branded as a kind of “M” – a codename for current or past heads of MI6 in the James Bond films – after directing covert operations from his office.

It was rumoured that Heslop would meet financial regulators informally over tea in the Palm Court of the Waldorf Hotel for certainty that the snazzy pianist would prevent their conversations from being overheard.

He also acted successfully for Taki, a society columnist, and others who were being attacked by Mohammed al-Fayed for funding Neil Hamilton’s libel case. Even though Taki’s volatile articles in The Spectator bothered the judge, Heslop convinced them to see his client as an 18th-century Grub Street journalist who should not be taken seriously.

Heslop was also seemingly a charitable man and his determination to enable disadvantaged people to study law led to his fundraising and contributions to Christ’s College.

Despite living a pleasant life, surrounded by great friends, such as politician Leon Brittan and dramatist Harold Pinter, his phobia of doctors would prove fatal. After wearily contemplating what he believed was gout, Heslop was rushed to the hospital and died of septicaemia.

King Charles’s contributions to Varsity, however, did not end at a look-alike. For Varsity’s twenty-first anniversary, the King spilled what his first impressions of Cambridge were. Despite “receiving so many admonitions about” writing for Varsity before arriving at Cambridge, the King decided: “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em!”.

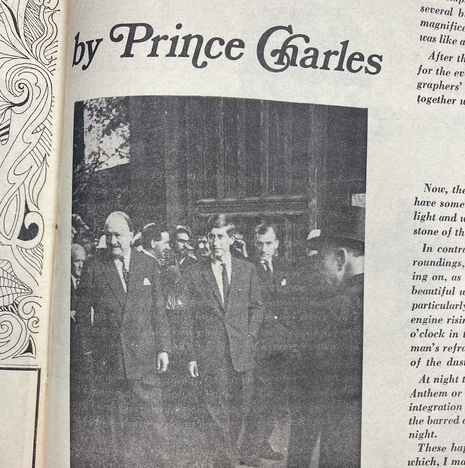

The King recounts being “wedged into a Mini, which is a form of travel not normally employed when there are people to meet upon disembarkation.” Because of this, he explains, “first impressions took on a distorted aspect because all that could be seen in front of Trinity Great Gate were serried ranks of variously trousered legs, from which I had to distinguish those of the Master and the Senior Tutor”.

Appealing for sympathy, King Charles says “if you have ever tried to get out of a Mini, you will know through what contortions you have to go”. After having “performed these in front of quite a large number of people, [he] was taken through the gate and into Great Court”.

He also compared the “burly, bowler-hatted” porters dragging shut Trinity’s wooden gates to “a scene from the French Revolution or some other” before remembering how “rewardingly silent” Great Court was. Well, despite “the everlasting splashing of the fountain and the sound of photographers’s hob-nailed boots, or their equivalent, on the ringing cobbles, together with the click of shutter in lens”, of course. Nowadays all you have to beware is a man asking you what song you’re listening to instead.

The King was also no stranger to “night activities going on,” or at least the ones that occurred “directly under [his] detached and innocently beautiful window.” This was something, the King explains, “he had to accustom [himself] to, particularly the grinding note of an Urban District Council dust lorry’s engine rising and falling in spasmodic bursts of agonised energy at 7 o’clock in the morning, accompanied by the monotonous, jovial dustman’s refrain of ‘O come, All Ye Faithful’ and the head-splitting clang of the dustbins.”

“At night too,” it was also “hard to ignore the timeless notes of the National Anthem or ‘Land of My Fathers’, punctuated by the melodious disintegration of bottles and merry voices raised in conversation, reaching the barred confines of [his] room at some unearthly dark watches of the night.”

If you thought the King had never banged his head on the wall in frustration, think again. He compared “these happenings” to “beating your head against a wall, which, I may say, I do frequently when the conditions are satisfactory”.

Overall, “these happenings” did in fact “contribute to [his] experience in Cambridge”, and, the King hoped that “in some very small way, [his] brief exposé will contribute to the celebration of the 21 years (shall I say of service?) given by Varsity.”

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026