Praying in fishbowls

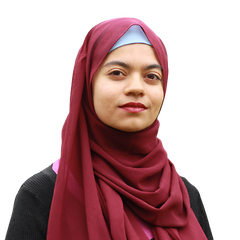

As Ramadan comes to an end, Staff Writer Imaan Irfan reflects on the visibility of her religion and how she’s grown to embrace it

Two glass walls with two glass doors, wedged between a bustling corridor and a classroom emanating with shrieks. These transparent walls punctually offered up a strange spectacle every lunchtime: an aquarium operating between 1 and 1.15 PM, where onlookers, like children pressing their sticky noses against the glass, could observe its sole occupant rising and falling. Up and down, up and down. A blue fish in a blue scarf.

In the religious melting pot known as Guildford, this was my school’s multi-faith room. Dubbed “the Fishbowl” by the few students that used it, its narrow carpeted floor provided a designated space to fulfil the daily prayers that intersected with school hours.

“In Islamic tradition, the whole earth is a mosque”

Muslims are familiar with praying in strange spaces – seeking bizarre nooks for moments of divine connection at regular times, finding stillness amidst the whirl of life. We pray behind DofE tents and at the backs of cinemas, changing rooms and in car parks (or even in Nando’s with a makeshift napkin prayer mat). In Islamic tradition, the whole earth is a mosque.

But the Fishbowl was no Cambridge Central Mosque. In a town where Mecca means bingo, and a date is more likely to mean flirting in the local Creams than the amber-brown mejdool used to break your fast, this wasn’t unforeseen. Instead, the deputy headmistress took it upon herself to scour the room; the bag stuffed with prayer mats and scarves that I’d tuck under a purple armchair was frequently confiscated. We were requested to not touch the blinds, after all, it was already a privilege to be allowed “unsupervised activity on school premises”. Attempts to resist the panopticon were made futile by the fact that the doors didn’t even have blinds. Depending on which side of the corridor was less busy on any particular day, a tactical decision would have to be made. Would I rather be seen by the groups chatting in their classroom, or by people walking past in the corridor? Only partially protected by the “room in use” signs I’d blue tac to the door, my heart would thump every time I heard footsteps, or the slow creak of a door.

I had unexpected visitors on more than one occasion: once, a Maths teacher, flanked by two adults, walked in and caught me standing by myself in the centre of the room, without any shoes. I sheepishly tried to slip my boots on, pretending this was totally ordinary despite the confusion written on her face. On another day, I distinctly remember hearing a group of girls enter the room from behind me, chatting as I sat on the floor in prayer with my hands resting on my thighs. There was a shift in the air as they registered my presence in the room. They paused and went silent, before bursting into laughter and continuing through to their classroom. They left both doors open.

“I was ready to accept my own visibility, but this time I would be seen on my own terms”

In these moments, acts of private connection became public exhibitions. Focus and contemplation were quickly usurped by the anxiety of potential disruptions and intrusive gazes – yet, that visceral feeling of vulnerability was met with the resolve to “get over it”. Prayer was a reminder that I was tied to my convictions and a relationship with my creator more than to my own insecurities, desire to fit in or fear of other people. At the end of it all, I’d still leave with a feeling I can’t articulate, with tranquillity and contentment and less stress than I’d walked in with.

I think my adolescence made me comfortable with discomfort. The readiness to inhabit and claim spaces in which I felt alien, defiance which manifests itself through a collection of brightly coloured headscarves, was one which I took with me to university. I took comfort in another Prophetic narration: "Islam began as something strange, and it will return to something strange, so blessed are the strangers". The idea of strangeness didn’t phase me anymore. I was ready to accept my own visibility, but this time I would be seen on my own terms.

Ironically, it was Cambridge – the very same Cambridge of punting, postcards, and privilege – that gave me a community which extended its palms to me with solidarity and warmth, one which made me feel less “strange”. We spend Ramadan in a college dining hall where the ceiling is frosted like a wedding cake, and my friends press our shoulders together in prayer after sunset. We pray on the lawn of King’s Parade, on the gravel of St John’s, and at the foot of Castle Mound as the sweet smell of rain seeps into the earth. On Ramadan nights, we cycle to the eco-mosque where a garden of tulips is flourishing. In the University Library, I glimpse somebody’s blue prayer mat peeking out of a corner. I smile to myself.

As I write this while sitting on a cushion in the prayer room on Sidgwick Site, Ramadan is nearing its end. Sunset is marked by the crackle of greasy paper as hungry students unwrap their discounted Pepe’s. This space is a classroom, a cafeteria, a library, a study spot, a debating chamber, and a mosque. It has neither glass walls, nor purple sofas, but it is home to so many people: those squeezing in prayers between lectures or panicking over dissertations, chatting and holding lengthy discussions on metaphysics, and reciting Quran.

I feel as though I’ve left a fishbowl, and found the ocean.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026