How I learnt to escape the trap of the male gaze

Megan Byrom reflects on how lockdown forced her to reevaluate her relationship with how she presented herself and the effects of the male gaze

I’d seen the male gaze before.

It was there in a perfume advert. The scene constructed was a fantasy, with a girl standing barely clothed and a cigarette hanging delicately from parted red lips. She rolled around silk sheets before drawing back the curtains and unveiling Paris outside of the window.

The leading heroine in a Hollywood film was similarly afflicted as the script directed her to laugh and she obliged, the camera panning away from her face and across her body. She didn’t have many lines, but ‘not everyone needs to speak’ defended the director.

Thankfully, it made the love interest of that novel nothing like ‘other’ girls. This one was different, eccentric and had a sarcastic answer for each of the protagonist’s problems. But, even her oversized clothes couldn’t save her from the author's gratuitous description of what’s underneath them.

These were tropes to me, superficial depictions of women as sexual accessories. From ‘the girl next door’ to the ‘blonde bombshell’, the male gaze is most commonly understood as the sexualisation of women in media, through the lens of a heterosexual man. I saw myself as an observer, rolling my eyes as women’s existence and validity became tied to their relationships and value according to men.

“I felt like I was being watched, constantly judged by something I couldn’t name”

However, the male gaze is not just a directorial decision or media trope, neatly constrained to pages, screens or lyrics, but something more, and in the silence of lockdown, I realised its eyes upon me. In those listless quiet days of the initial lockdown, there was nothing to distract me from the way I was behaving. The public had retreated into isolation and I was alone. Yet, I felt like I was being watched, constantly judged by something I couldn’t name, it wouldn’t let me leave the house, even for my daily exercise without trying to look good. From the way I moved, talked, or dressed, I was acutely aware of how I presented myself.

Before lockdown, I acted like this too, paranoid that my attractiveness was being continually calculated by those around me. But completely alone during a pandemic, I began to question whose approval I was seeking.

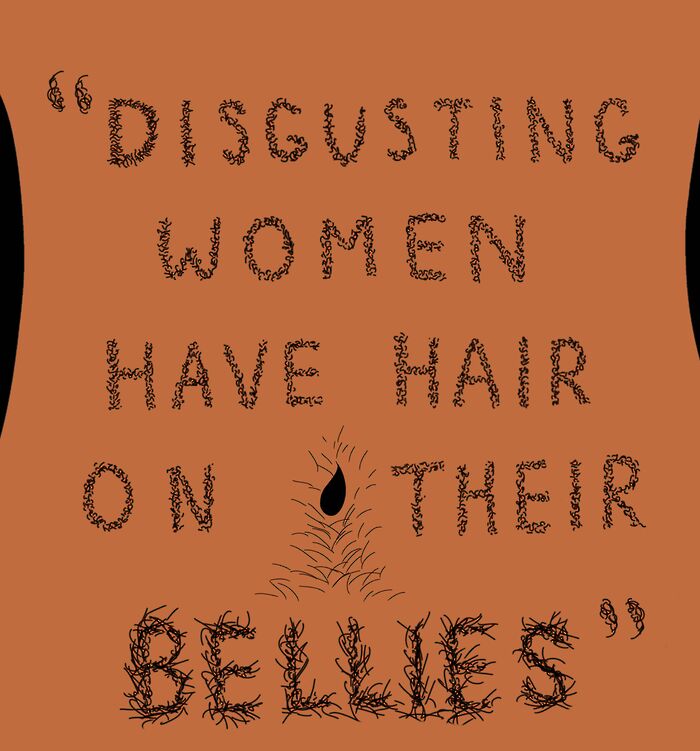

It wasn’t normal, performing as if I was being observed, the incessant reminder to present myself as attractive at all times in case someone was watching. I realised the male gaze was something more social. It wasn’t about being watched by men but being trained to act as if you are, whether that’s as extreme as covering up for safety or imaging the opinions of men even when entirely alone. I had internalised this perspective and was struggling to detach myself from it. How had I come to absorb this?

Existing within the male gaze is gratifying and before lockdown, I knew it. There’s a privilege in fulfilling the beauty standard, one that can detract from the abuse, violence and difficulties faced by women outside of it. Life is easier when you’re not the punch line of a joke or so openly harassed by prejudice. Performing to the expectations of the male gaze gave me a platform, opportunities and superficial confidence that came with compliance. From being listened to in social interactions with men, to being hired for a part-time job that only took on applicants ‘with a certain look’, the male gaze had a hold on me economically, socially and culturally.

“Whilst the internalised male gaze is difficult to depart from, lockdown has perhaps given me an opportunity to try”

In that first lockdown, when this became clear, I told myself it was a choice. Feminism had reassured me that these things, makeup, clothes, self-sexualisation, could be liberating. It was a post-modern revelation, that feminism could align with the traditional male gaze. The concept of choice had become all-important and I had found comfort in believing that these things were autonomous decisions.

But it had stopped being a choice for me, I was adorning myself with traditional femininity worried that I’d be criticised for not doing it. It had become a daily prescription to make me comfortable in my own skin. Lockdown forced me to confront that perhaps I’d picked up the very same tools used in my oppression and tried to turn them into something liberating.

However, for me, it wasn’t empowering anymore. It wasn’t simply about aesthetics, but an understanding that my sense of self had altered. This constant performance of the ideals of the male gaze had begun to define how I understood myself I wanted to enjoy these things and rediscover them on my own terms, as accessories this time, things I could take off that were not stitched to my sense of self.

But unlearning the male gaze is not easy.

Even in the isolation of lockdown, I find that it's still there. Whether I’m walking along Kings Parade or alone at my desk, I still scrutinise myself through this lens. Whether it’s my bare face, my body, my clothes or how I look on a Zoom call, it’s difficult to silence a voice telling you women always have to present themselves as attractive.

As Margaret Atwood stated in her novel The Robber Bride, even “pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies, is a male fantasy.” The pervasiveness of patriarchy and expectations of the male gaze are deep and hard to overturn.

Whilst the internalised male gaze is difficult to depart from, lockdown has perhaps given me an opportunity to try.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026