Rethinking the ‘perfect’ student

Vulture Editor Georgina Buckle writes on the sacrifices that are and aren’t worth making as a Cambridge fresher

Going up to the Cambridge University Open Day I had prepared a list of questions, most of which were answered by smiling students and reassuring academics. There was only one answer that I remember inciting apprehension in me, from a professor of English. Naturally concerned given Oxbridge’s notorious reputation of heavy workloads, I had asked him “realistically, would I be able to have hobbies and time to socialise as well as staying on top of my studies?”

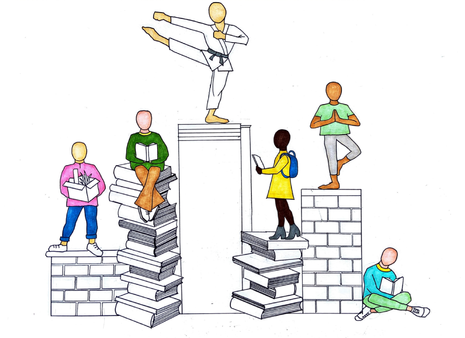

His answer wasn’t particularly heartening. “Well, if you are very careful with your time, and don’t get distracted by Facebook, you’ll perhaps be able to manage your taekwondo on top of your studies.” Although not inherently wrong, his response seemed to be a firm way of saying: if you’re able to manage your time like a machine and robotically disconnect from any distractions, then yes, you’ll have room for exactly one extra-curricular activity (with time for socialising worryingly excluded). I applied nonetheless, knowing full well that I wasn’t the machine-like student he described, despite being a keen and hard-working one.

Throughout my education, I’ve always – shock horror – liked studying. My A Levels proved to me that I could be a ‘good’ student by working hard, even if I saw my friends often and gave time to non-academic activities. I can procrastinate work, or inefficiently spend far too long trying to perfect one task, or simply be distracted – as I said, I’m not a machine.

“In retrospect, I had to change my preconceived ideas of what the ‘perfect’ student was”

In spite of all of this, I had enough time to put in my hours of studying during the week. I thought I was a ‘good’ student because I was never usually forced to work late, or last minute and my teachers’ praise and good marks affirmed this. It’s therefore unsurprising that the professor’s response made me nervous that I’d have to severely change who I was and what I liked doing outside of academics in order to fulfil my wish of still being the ‘perfect’ student. In retrospect, I had to change my preconceived ideas of what the ‘perfect’ student was.

Coming to Cambridge was certainly a shock to my previous routine. The heavy workload was expected – two essays and multiple other tasks on only the second day of being a fresher – but was still challenging to get used to. I was adamant to keep time for relaxing or socialising, even just for spontaneous nights chatting late with my flatmates, but had to face the consequence of this. In my first term, I found myself spending nights in the library until 4am. Working so late and being forced to do tasks last minute – simply because of the sheer workload – made me feel guilty that I was a ‘bad’ student, despite still putting in the hours and finishing my work.

I was adamant I wouldn’t wholly sacrifice doing ‘normal’ student things, like going to see shows at the ADC, trying out a sports class, doing yoga, or getting involved with Varsity. So instead I had to shift my focus onto what the ‘perfect’ student was. It seems a simple thing, but I had to realise that it was justified to change routine in the midst of a huge life transition. You’re balancing living away from home with adapting to a demanding academic course, and people do truly mean it when they say that the first year is full of trial and error.

“Even the nicest professors will never tell you that you have done enough work, or learnt enough, and that’s normal”

As well as this, I had to adapt to an entirely different understanding about essays. During A Levels, homework essays were the pinnacle of hours of in-class and at-home learning; they were supposed to be polished, finished products. At Cambridge, I realised professors see them as germinating ideas still being worked out and tested – the first step of learning, rather than the last. This encouraged me in later terms to spend less time inefficiently trying to be a ‘perfectionist’ on topics that I would never be truly finished learning about. Even the nicest professors will never tell you that you have done enough work, or learnt enough, and that’s normal – you’re paying to be a student, not a teacher.

This is all far easier written in hindsight than felt during the time, when the change can be overwhelming. Turning to the people in the years above helped, like making use of the bizarre college family set-up to ask my two wonderful Mums for guidance. But my main advice to freshers that are in the position I was in, is simply to allow change to happen – including a change to how you perceive the ‘perfect’ student.

The professor at the Open Day was right in some respects. In order to stay afloat of the work and try to avoid late nights in the library, I have learnt to be better at prioritisation, and efficient working. At the same time, I know I will never wholly bend my student routine to fit a rigid, mechanical mould – if I have some late nights studying as a result, maybe that’s a sacrifice worth making. I’m not a machine, but that never made my first year impossible.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026