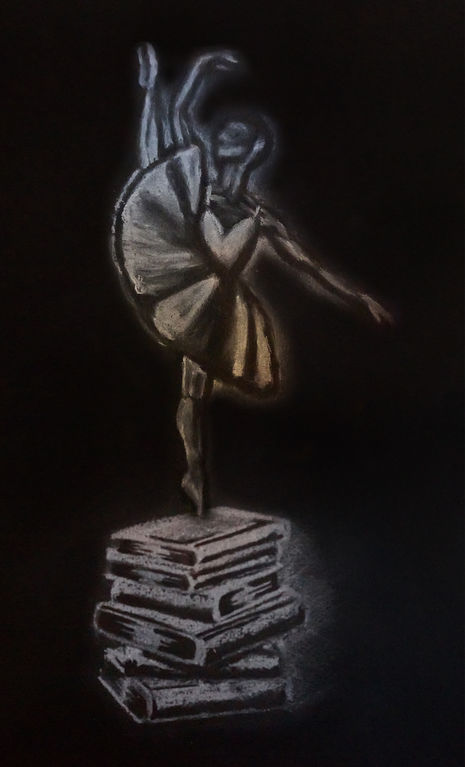

Resisting the commodification of education: Applying the mindset of dance and creativity to my degree

Stella Rousham advises one to make it through term-time to our own choreography, to stay in the moment and enjoy the learning process rather than being obsessed with the end result

‘I was so unproductive today’, ‘my essay is so bad’ or ‘I’ve done no work’: statements that virtually all Cambridge students say at one point or another. It would be hypocritical of me to say that I don’t also frequently feel and say these things – I do all the time – and ticking off items from your to-do list or sending in an essay whilst moaning about not working hard enough is certainly something very enjoyable.

Yet, after reading the recent email from CUSU which called for students to ‘boycott’ the National Student Survey which is putting our education ‘at risk’ through ‘marketisation’, I realised more than ever that the way students feel, approach and measure their success, self-worth and progress is a political issue. Mass commodification has served not only to diminish the purpose, nature and aim of education, it is also adversely affecting student and staff mental health.

I constantly critique my lack of productivity, burdened by feelings of inferiority. As an act of political, radical self-care, I like to think about my learning through dance and creativity, placing value on the process rather than end result and the embodied experience rather than the quantifiable grade.

Having danced throughout my time at school and now during university, it is a huge part of my identity and has fundamentally shaped my worldview. I first started ballet at my local dance school when I was 6 years old and before I knew it, I was training over 10 hours a week as well as holiday intensives.

“As an act of political, radical self-care, I like to think about my learning through dance and creativity, placing value on the process rather than end result”

Ballet will always have a special place in my heart, but it is highly problematic. I soon grew frustrated with its antiquated gender roles and rigidity. However, where ballet made me feel like I was constantly striving for an impossible ideal, contemporary dance allowed me to develop my own artistic voice and movement vocabulary. It was in contemporary classes that I had the opportunity to experiment with choreography; our classes involved a myriad of creative tasks which ranged from using props, to dancing blindfolded, to undertaking site-specific choreography in places such as lifts and museums. There was never any kind of assessment: if we performed our work to the class, it was a means of sharing it rather than putting it up for ranking and judgement.

University tuition fees first marked the pernicious commodification of education, serving to turn universities into brands, degrees into products and staff into dehumanised service providers. Comparing this to my alternate education through dance, I can’t ignore how damaging it is. The commodification of education has misconstrued the purpose of learning; positioned as a means to an end, learning is valued only because it offers the possibility of bringing ‘real,’ monetary value.

Taking dance and choreography classes has taught me otherwise: learning is a process and an embodied experience. In a dance class, the learning is felt; it is in the moment, it is a procedure. You cannot abstract the learning from outside of yourself, quantify it or evidence it on paper. You know you have learnt something because the movement feels different to anything you have done before.

Choreographic and creative practices stress the importance of the process: when compiling movement, the emphasis is on exploring the idea that generates the movement rather than achieving an ultimate goal. The supervision system at Oxbridge has remnants of this embodied approach to learning - and thus has never been so precious and worth defending. This personalised learning experience flies in the face of marketised, exam-factory education - allowing students to grow as people, not products. Supervisions indicate what education should look and feel like, and it is an approach that should not be limited to the privileged few at Oxbridge.

“Let’s put one foot after the other and make it through term following our own choreography, and enjoy what should ultimately be a pleasurable experience”

Students are not only being positioned as consumers purchasing their degree, we are also being manufactured as fully formed commodities ready to be purchased and consumed in the labour market, like fast food or ready meals. If students are being mass-produced, then the components that make us up are unhealthy; akin to a McDonald’s burger, the only thing that matters is for the end result to be marketable. Hence, when I hear everyone constantly talking about how ‘unproductive’ they’ve been, I can’t help but fear that we have internalised this striving for marketability that is omnipresent in the education system, and have applied it to value our self-worth.

For me, dance and choreography offer health benefits. For dancers, the body is our instrument, and so it matters immensely how you nourish and nurture it - physically and mentally. The holistic nature of dance can remedy the unhealthy attitude I have the tendency to develop towards my learning, allowing me to recognise that my work and ‘productivity’ is inseparable from how I feel and how I care for myself.

Especially during A-Levels, dance classes were one of the few ways that I could relieve stress, because dance is mindful. When dancing, you have no choice but to be in the present; there’s no time for anxiety or doubt when you’ve got to split leap to the otherside of the room in 4 beats. When I reflect on the weeks I’ve been most stressed at Cambridge, I realise it is because dance was absent. So why not be in the present; enjoy the essay or maths paper, conduct our lab experiment focusing on the learning process? Let’s put one foot after the other and make it through term following our own choreography, and enjoy what should ultimately be a pleasurable experience, instead of constantly dreading the future.

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Arts / Modern Modernist Centenary: T. S. Eliot13 December 2025

Arts / Modern Modernist Centenary: T. S. Eliot13 December 2025