When self-care becomes self-sabotage

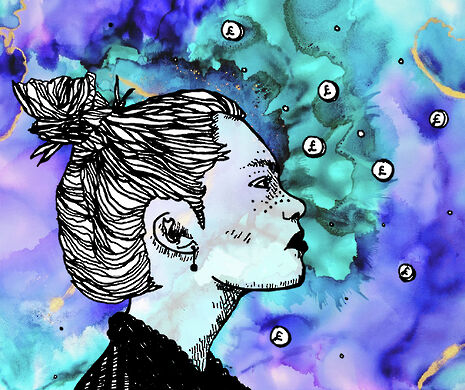

Olivia Emily reflects on how ‘treating yourself’ as a strategy of self-care can often turn into a form of self-sabotage

‘Treat yourself’ is a phrase I became very well-acquainted with during my first year at university. Having thousands of pounds in my bank account for the first time in my life appealed to the hedonist in me, the Rebecca Bloomwood shopaholic that had never had the funds to truly blossom.

So I got into the habit of buying myself presents at the end of stressful weeks or emotionally-draining conversations with my college counsellor: new trainers to facilitate the spring I wanted in my step; take-aways so I wouldn’t have to face the cafeteria; jeans that didn’t really fit right and I’d donate out of guilt just a few weeks later. ‘It’s self-care,’ I told my friends as a way of justification if they ever commented on my new purchases. They only laughed in response, the whole concept of ‘treating oneself’ still somewhat of a meme.

The feeling of spending money ‒ getting something new, receiving the perfect gift (even if it’s from me to myself) ‒ is unparalleled. I can look in the mirror and like what I see, even if I am just seeing a new dress and not actually seeing myself. But, in my experience, this ‘treat yourself’ configuration of ‘self-care’ is as superficial as a plaster when it comes to healing wounds, and it’s where ‘self-care’ starts morphing into self-sabotage. By spending money instead of addressing my problems, I never truly had to face them, meaning I also never dealt with them or found ways to get better.

It’s damaging to perpetuate the idea that finding new ways to change yourself is equivalent to loving yourself

I’ve also historically fallen into borderline-destructive ‘self-care’ habits, like skipping out on social events because I was feeling low, or switching off my phone because it was making me anxious. While these things do serve as temporary support ‒ and it’s good to learn to enjoy your own company ‒ there’s a difference between the odd self-care evening alone and isolating yourself. As painful as it sometimes initially was to go to those social events, isolating myself from people who care about me meant I never allowed myself to be helped. It’s got a lot to do with self-worth ‒ realising that I’m worthy of other people’s time and care is one of the first steps I took in recovery, even if, initially, that only mean talking to my Tutorial Advisor about how I was feeling.

Summers have always been periods of regeneration for me: It’s when I start having skin routines again, find a new style, and write endless lists of goals in journals. That is an example of modern self-care ‒ the self-care I’ve always bought into. But it’s damaging to perpetuate the idea that finding new ways to change yourself is equivalent to loving yourself. This summer, I realised that I’d run out of boxes I wanted to squeeze myself in. How could I be caring for or loving myself if the whole act of ‘self-care’ involved changing who I had just been for a year? Instead, my self-care has finally morphed into something more constructive: listening to what my mind is telling me, and finding healthier ways to care for myself that didn’t somehow involve simultaneously tearing myself down. I wanted to focus on true ‘self-care’ and building a sense of self-worth to go with it.

‘Self-care’ is tricky territory to navigate, because it’s closely-related to self-love ‒ which still seems a bit bizarre to me in the context of British modesty and self-deprecating humour. I’ve been trying to check my over-modesty: for example, I now try to say ‘thank you’ instead of ‘sorry’ ‒ ‘Thank you for bearing with me’ instead of ‘Sorry I’m such a mess’ ‒ or accepting compliments outright rather than deflecting them. The best forms of self-care are often as simple as changing those small habits, or even just getting enough sleep, eating well, exercising, socialising, and acknowledging how you feel. The hustle and bustle of a Cambridge term can make even the simplest of things seem difficult, sometimes, so I’m using summer to get into good habits that I’ll hopefully be able to transfer to the academic term in Michaelmas. For example, I’ve found that writing my thoughts down ‒ without worrying about how neat it is, or if it makes sense, or what if someone reads it ‒ helps me to process them.

Until then, the Long Vacation is also the perfect time to get some headspace and reconnect with myself and my needs. Phrases like ‘treat yourself’ taught me that buying myself things or indulging in an evening alone would make me feel better. Though this is good for short-term relief, the ephemeral joy and relief of spending money can only ever briefly mask the pain and stress I feel; it cannot deal with it properly. True self-care is realising that a new pair of jeans maybe isn’t the answer right now.

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026 News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026

News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026 Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026

Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026 Features / Exploring Cambridge’s past, present, and future18 January 2026

Features / Exploring Cambridge’s past, present, and future18 January 2026 News / Your Party protesters rally against US action in Venezuela19 January 2026

News / Your Party protesters rally against US action in Venezuela19 January 2026