Disarming the canon: the importance of content warnings

Harmful reactions to course texts can easily be prevented through proper and full content warnings, writes Isabella Leandersson

Content Warning: references to sexual violence and r*pe

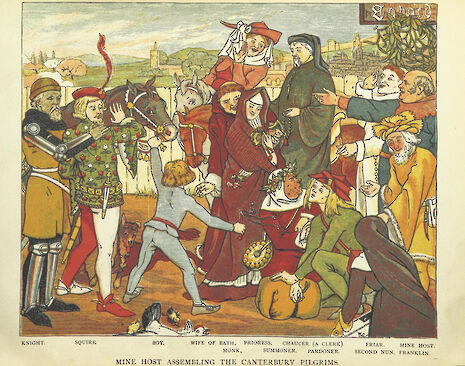

Last summer, I decided to try something drastically different. I decided to read my reading list for Michaelmas term ahead of time, instead of scrambling to do it on top of everything else during term time; why prepare when you can spend eight weeks one sonnet away from an ulcer? Dutifully I made my way through Chaucer, which if you’ve seen it you know, is less of a book and more of four-bedroom bungalow. I was doing alright with the trite sexism of it when something changed as I got to the Reeve’s Tale.

If you’re fortunate enough never to have read it, I’ll give you an overview. The Reeve’s tale follows the Cambridge-educated and oh-so-mischievous protagonists John and Aleyn as they decide to punish a miller’s greedy ways by tricking him. Instead, the poor boys are cheated by the miller and stranded at his house. Nasty, right? He totally has it coming. Well that’s why John and Aleyn decide that the best way to get him back is to rape his wife and daughter. We follow these two gentlemen as they go about their plan, told in tell-tale Chaucerian light-hearted fashion. We witness every step of the plan, learning at the end what a fitting way this was to punish the miller.

“This not only invalidates the survivor of sexual assault to others, but can stunt the survivor’s own journey to healing”

Now, this was written in the 14th century, when women were little more than sexy Roombas capable of reproduction. That’s why I anticipated the sexism, the objectification, the silencing of women’s narrative. That’s why I was pleasantly surprised at points where Chaucer seemingly gave women agency (see the Wife of Bath’s tale, although that one also features rape because why not). It was the inclusion of this tale, specifically on my reading list as one out of more than fifteen tales selected as the most relevant reading, that surprised me. What was so important about this tale? Nothing, it turns out. We didn’t even study it during term.

I’m not saying it emotionally wrecked me, I didn’t even have a panic attack. I just sort of sat there as my brain said nope and dissociated. I spent some time feeling like I was thirteen again and just beginning to remember. I wondered if my perpetrator thought it was funny too when they transgressed against me? Now, don’t get me wrong, this is all easy stuff to deal with. A little self-care, a few antihistamines, zopiclones, and fluoxetines later and I was great. But I’m 21, I’ve had almost five years of therapy and accompanying medication, and I haven’t been alone with my own mind for a very long time.

It’s not the first time a piece of set text has affected me like this, and I’m not upset with supervisors who set the reading, it is part of history and a part of literature, it should and deserves to be studied, picked apart and criticised. It is important. I understand that to the people who set it, it is just an interesting piece to be studied. I’m glad that it isn’t as live-wire for them as it is for me, but I don’t have that privilege of distance that they do.

“All I ask is for an opportunity to choose my battles”

Leading up to this, I shared an anonymous survey to see what other people’s experiences were, and one person said that “sometimes supervision conversations about these issues weren’t particularly considerate, or in fact were discussed in a humorous way”. This is the problem with texts like the Reeve’s tale that are comedies featuring abuse or assault. If the source material isn’t contextualised properly, or handled carefully by the supervisor, the conflation of its humour with its content only extends to the supervisions themselves. This not only invalidates the survivor of sexual assault to others, but can stunt the survivor’s own journey to healing.

I don’t wish to paint a dystopian picture – some of the people asked had positive things to say. One described how “when my friend explained why she wanted to study the text without sexual assault in it our supervisor was perfectly understanding”. In this case, the system worked, the text was not compulsory and the student could switch to a different one. This is not, however, a universal policy, as people seem to assume. I often hear how I can ‘just ask [person’s name] and they will understand’. But that’s not necessarily the case. One student said they were “Told to deal with it and that they can’t be seen to be giving me an advantage.”

Truthfully, it’s a bit of a lottery. The treatment you receive is entirely down to the temperament of your supervisor. There is no universal rule on content warnings, some lecturers do it, some don’t, some supervisors include a sentence giving you a head’s up about the contents of a set text, some don’t, some supervisors will help you and be understanding and wonderful, some will tell you to suck it up and stop messing with the canon. Why should the extent to which someone’s traumatic past is respected vary depending on whether their supervisor can relate?

Finally, I would like to add that I am under no illusion that I will ever live in a world – academic, professional, or otherwise – in which I will be entirely protected from sexual violence. I am not naïve in my victimhood. I do not expect the world to change for me. All I ask is for an opportunity to choose my battles. If the Reeve’s tale isn’t going to be studied, why should I have to read it? If it is essential that I read it, can I not receive some warning? Just a simple head’s up, and I’ll take my betablockers and go for a long walk and adjust my own schedule, my own precious time, not yours, to handle it. I am not asking for you to be inconvenienced in lieu of me, I am asking for the right to manage my own inconvenience. There will never be a world in which what happened to me, to us, never did. But maybe there can be a world in which we can see and expect the ghosts that haunt us, before they spring on us in the middle of the night

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025