A human pinball in a germ warfare experiment

Alex Nicol reminisces about his first time in a club

To prink (verb): The art of pre-drinking at a friend's house in order to save money on a night out.

Got it. Definitely a better idea to look that up on Urban Dictionary than out myself as that one guy in college who’d never been clubbing before. Coming from a rural backwater where the average (usually retired) resident takes walks in muddy fields for excitement, the closest I’d ever got to a club was an overcrowded pub. But come my second night at Cambridge, I was determined to give it a go. I felt I’d kind of be failing Freshers’ Week if I didn’t. I was going to be a normal teenager with a vengeance.

So I zeroed in on the hyperactive hum of human voices leaking through the walls of one of the rooms just down the corridor from mine. This was it, then: the prinking arena. And I was its biggest lightweight. As I sipped timidly on my tame 3.5 per cent beer, the professionals were steadily downing their vodka shots, stoically seeing off anything that came before them. For a few brief moments, their facial muscles would squirm, wriggle and ripple in what could have been a guilty betrayal of pain. Then they settled, gracefully recovering their composure. These were the hardened veterans of the big cities, reflecting only the slightest glint of weakness before they reached towards the next shot with a steely resolution that, I have to admit, was kind of impressive. Maybe Urban Dictionary was right – this was a weird kind of art form in its own way.

“I was confronted with something that looked like a nuclear bunker and smelt like a germ warfare experiment.”

They were really nice people, I soon learned. One of them even offered me one of the Frankenstein cocktails he had concocted for himself. If it wasn’t for the way each individual droplet grated the inside of my throat like a molecular razor, it probably would have tasted decent. Did I want another? My tongue would only clumsily splutter a few garbled syllables before it let me choke out what I hoped was a polite refusal. Fair enough, no problem. We were all about to make a move towards the actual club in a minute anyway.

Soon enough, we were lined up outside this so-called ‘Life’. Well, sort of lined up. Whoever said that the British were good at queuing had clearly only visited Waterstone’s in daytime. But we’d stood our ground in the scrum for a good three quarters of an hour, so whatever was in there had to be good, surely.

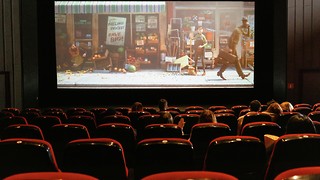

It was actually a bit of an anti-climax. I was confronted with something that looked like a nuclear bunker and smelt like a germ warfare experiment. As I got knocked around the room like a human pinball, I couldn’t help wondering whether I’d basically just paid £4 to spend the night in the London underground, stuck in some kind of time loop of the rush hour. As for the music, the only other place I’d heard that kind of electronic diarrhoea was probably in one of those old-fashioned arcades you still sometimes get outside bowling alleys. It was like someone had taken all the sound effects from Mario Kart and mashed them all together as a joke. Then the Lion King theme started playing, which I decided actually had to be a joke. That was genuinely quite funny. What I wasn’t so amused by was some random, sweaty six-footer deciding to use my collarbone as a pivot to pump himself up and down to the beat like a piston. That was when it clicked. You don’t go to the party to get smashed, you get smashed because you’re at the party.

Even the margarita maestro who’d offered me one of his cocktails earlier was flagging. “I’m so not drunk enough for this, mate,” he informed me. What, like not having enough anaesthetic before an operation? For anyone as luridly lucid as I was, this was getting a bit much. It certainly was for at least one of the other freshers, her gaze surreptitiously flickering towards the exit. We skulked towards it and, with a few others in our wake, slipped out into the open air.

A colourful cast of characters emerged: a surfer apparently suffering from Tourette’s syndrome with the word ‘dude’, a self-proclaimed magician and a Polish Anglophile who was fascinated to know exactly what I thought about Radio 4, for some reason. Chatting, laughing, and joking as we drifted back home, the fact that we would have had nothing to do with each other in any normal situation didn’t matter. The very fact that it wasn’t normal was, I began to feel, what made it special.

So that was it: the rite of passage. I had finally been initiated into that teenage twilight: floating between freedom and responsibility, opportunities and commitments, childhood and adulthood. It’s a psychological limbo which doesn’t offer its travellers much to hold on to save each other. Maybe that’s why, when I eventually returned home, I found myself missing that soothing buzz of chattering voices filtering through to my room. There was that reassurance that, just a few paces away from you, there was a hive of human activity where anyone, even someone as classically uncool as me, was always welcome. I think I’ll miss it more when we’ve all finally grown up for good.

News / Cambridge to have ‘England’s first official cycle street’7 October 2025

News / Cambridge to have ‘England’s first official cycle street’7 October 2025 Lifestyle / Which Cambridge tradition are you?6 October 2025

Lifestyle / Which Cambridge tradition are you?6 October 2025 News / Gardies officially closes4 October 2025

News / Gardies officially closes4 October 2025 News / Jensen Huang, Celeste, and Mia Khalifa to speak at the Union5 October 2025

News / Jensen Huang, Celeste, and Mia Khalifa to speak at the Union5 October 2025 News / Uni clears don accused of ‘abhorrent racism’3 October 2025

News / Uni clears don accused of ‘abhorrent racism’3 October 2025